THE 1979'S IRAN REVOLUTION,IT'S CAUSES WHY THE LAST SHAH OF IRAN MOHAMMAD REZA PAHLAVI WAS OVERTHROWN.THE RELIGIOUS LEADER AYATOLLAH KHOMEINI RETURN TO IRAN AFTER 14 YEARS IN EXILE. IN 1980 SHAH IRAN PAHLAVI DIES IN EGYPTIAN EXILE,HE WAS 60 YEARS OLD.

The Iranian Revolution was a populist, nationalist and Shi'a Islamic revolution that replaced a dictatorial monarchy with a theocracy.Its causes – why the last Shah of Iran (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi) was overthrown and why he was replaced by an Islamic Republic – are the subject of historical debate. The revolution was in part a conservative backlash against the westernization, modernization and secularization efforts of the Western-backed Shah, and a more popular reaction to social injustice and other shortcomings of the ancien regime.

The Iranian Revolution was a populist, nationalist and Shi'a Islamic revolution that replaced a dictatorial monarchy with a theocracy.Its causes – why the last Shah of Iran (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi) was overthrown and why he was replaced by an Islamic Republic – are the subject of historical debate. The revolution was in part a conservative backlash against the westernization, modernization and secularization efforts of the Western-backed Shah, and a more popular reaction to social injustice and other shortcomings of the ancien regime.

The Iranian Revolution of 1977-79 was the first in a series of mass popular civil insurrections which would result in the overthrow of authoritarian regimes in dozens of countries over the next three decades. Unlike most of the other uprisings that would topple dictators in Latin America, Eastern Europe, and parts of Asia and Africa, the result of the Iranian struggle was not the establishment of liberal democracy but of a new form of authoritarianism. However, except for a series of short battles using light weaponry in the final hours of the uprising, the revolutionary forces themselves were overwhelmingly nonviolent. The autocratic monarchy of Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi faced a broad coalition of opposition forces, including Marxists and constitutional liberals, but the opposition ultimately became dominated by the mullahs of the country’s Shia hierarchy. Despite severe repression against protestors, a series of demonstrations and strikes over the previous two years came to a peak in the fall of 1978, as millions of opponents of the Shah’s regime clogged the streets of Iran’s cities and work stoppages paralyzed the country. The Shah fled into exile in January 1979 and exiled cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile to lead the new Islamic Republic.In 1941, concerned with the Shah’s pro-Axis sympathies, British and Soviet troops occupied the country forcing the Shah to abdicate in favor of his son, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. In the more liberal climate following the Allied victory in World War II, the democratically-elected majlis reasserted its power, electing the nationalist prime minister Mohammed Mossadegh in 1950. Soon thereafter, the Mossadegh government nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a British monopoly, which led to an international boycott of Iran’s primary export. As the economic situation deteriorated and political unrest grew, a power struggle ensued between the young Shah and the elected prime minister, with the Shah fleeing into exile in1953. A CIA-sponsored coup soon thereafter ousted Mossadegh and his nationalist supporters and returned the Shah to power as an absolute monarch. The oil companies were returned to their foreign owners, the majlis was largely stripped of its power, and leftists, nationalists, Islamists and all other opponents to the regime were ruthlessly suppressed.In the early 1970s, the Shah was regarded internationally as an unrivalled and ambitious dictator, as a devoted ally of the US and as enjoying excellent relations with the international community. Iran was seen as enjoying prosperity and economic growth as the Shah staged the extravagant celebrations of the 2500 anniversary of the Iranian monarchy at Persepolis in 1971. To avert political change, he himself introduced the so called “White Revolution”, an ambitious program of land reform, and set up his own political party, Rastakhiz, which had compulsory membership and dues,. Both of these created tension and dissent. During the late 1960s the Shah had become increasingly dependent on the secret police (SAVAK) in controlling those opposition movements critical of his reforms. The combination of SAVAK monitoring internal dissent and a vast army equipped with ultramodern weapons looking outwards, in the mid-1970s the Shah’s regime appeared durable. Despite endemic corruption and complex economic problems it was appeared that the regime was indestructible. However, movements against the Shah were gathering momentum inside Iran and amongst Iranians abroad. These included armed uprisings and underground movements inside Iran as well as the movements of the disenchanted clergy and the liberal nationalist movement, the National Front. The International Confederation of Iranian Students in Europe and the US often organized successful demonstrations during the Shah’s visits abroad to unmask his claim to popularity. At the same time the gradual rise in the price of oil through the 1970s led by the Shah through the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) angered the West while the parlous state of human rights began to gain international attention. But suddenly the Shah’s fortunes changed in just over two years A string of demonstrations, strikes and mass protests at home and protests abroad gained international attention.Under the Reagan administration, the United States agreed to secretly send weapons to Iran, then under an arms embargo amid its 1980s war with Iraq. Money earned from those sales went to fund American-backed Contra rebels fighting in Nicaragua. The Americans also hoped the sales would encourage the Iranian government to use its sway to help free American hostages held by the Lebanese Shiite militant group Hezbollah. When George H.W. Bush became president, he told Iran that “good will begets good will” and while American hostages in Lebanon were freed, relations never went further.

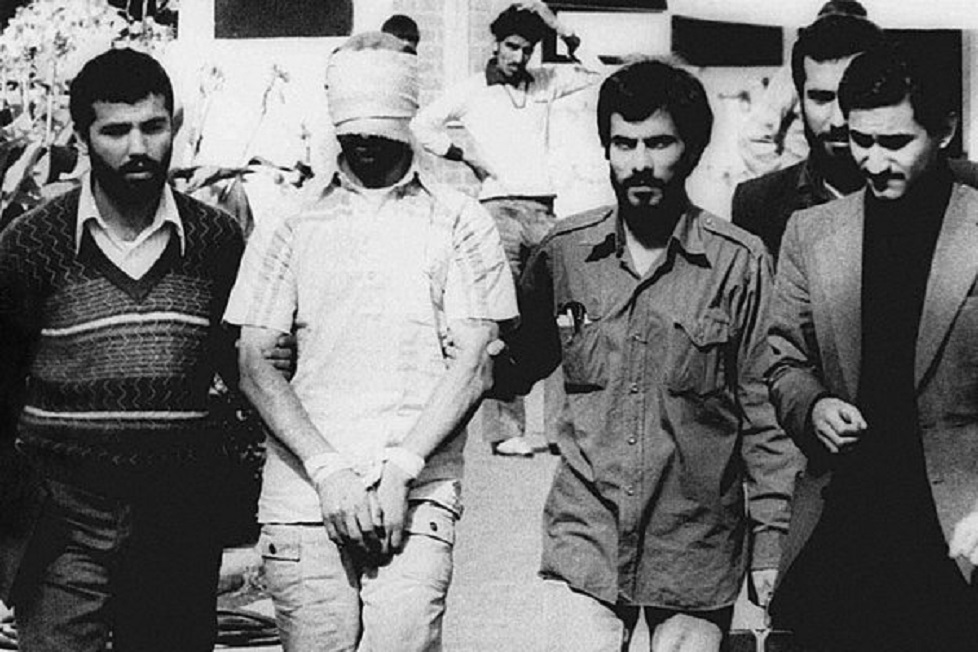

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi with U.S. President Jimmy Carter in Tehran, Iran, Dec. 31, 1977. during an official visit to Tehran in December of that year. At the time, though demonstrations had already begun to shake Iran and its U.S.-friendly monarchy, Carter called the country under the Shah’s rule an “island of stability.”Within two years, the demonstrations had snowballed into a massive protest movement, and the Shah fled Iran for good in January 1979. With the mullahs in the ascendancy, Iran soon became the Islamic Republic. In November, Iranian students overran the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, setting off a 444-day hostage crisis that severed diplomatic ties between the two countries.

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi with U.S. President Jimmy Carter in Tehran, Iran, Dec. 31, 1977. during an official visit to Tehran in December of that year. At the time, though demonstrations had already begun to shake Iran and its U.S.-friendly monarchy, Carter called the country under the Shah’s rule an “island of stability.”Within two years, the demonstrations had snowballed into a massive protest movement, and the Shah fled Iran for good in January 1979. With the mullahs in the ascendancy, Iran soon became the Islamic Republic. In November, Iranian students overran the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, setting off a 444-day hostage crisis that severed diplomatic ties between the two countries.

The Shah leaves Iran for ever.On 16 January 1979 the Shah leaves Iran with Empress Farah, never to return. Huge demonstrations have been ongoing since 1978.Egypt had been the first stop in their exile on 16th January 1979 when the imperial couple arrived in Aswan. But on the 22nd, Farah Pahlavi and the “king of kings”, who was suffering from terminal lymphoma, “a well-guarded secret since 1974,” were already on their way to Morocco at the invitation of King Hassan II.

The Shah leaves Iran for ever.On 16 January 1979 the Shah leaves Iran with Empress Farah, never to return. Huge demonstrations have been ongoing since 1978.Egypt had been the first stop in their exile on 16th January 1979 when the imperial couple arrived in Aswan. But on the 22nd, Farah Pahlavi and the “king of kings”, who was suffering from terminal lymphoma, “a well-guarded secret since 1974,” were already on their way to Morocco at the invitation of King Hassan II.

This largely peaceful revolution eventually replaced the order of the Shah with a system of governance ruled by the clergy and headed by Ayatollah Khomeini.The root causes of the revolution are complex and remain a subject of academic debate. But what is clear is that the period of the Shah's rule saw profound socio-economic changes in Iran, in large part driven by oil revenues. A near doubling of the population was accompanied by rapid urbanisation and increasing inequality. Socio-economic pressures and rising inflation, combined with pressure from the Carter administration in Washington to address human rights and rein in the Shah’s notorious security service (Savak), resulted in growing dissent by the end of 1977 and set the stage for the revolutionary fervour of the following year.By the time of the Revolution the press was finally free of the muzzles of the Savak and regained much of the vigour and dynamism lost at the time of the August 1953 coup. Between the fall of the Shah on February 11, 1979 and the end of that year the press enjoyed what is referred to as the 'Spring of Freedom', characterised by dozens of new publications.This lively and unique period in Iranian history is encapsulated by the press of the time, from the various anti-Shah political organisations which had emerged from years of repression, to tabloid dailies that juxtaposed gossip and light content with the celebration of the "martyrs" of the struggle against the monarchical regime. Press freedom, however, proved to be short-lived as the nascent Islamic Republic began to cement its grip on power. By August 1979 state control over the media was once again complete with the closure of the popular Ayandegan newspaper, which had acted as a beacon for non-clerical revolutionary groups.The Iranian revolution relied on many methods of unarmed insurrection—such as demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, contestation of public space, and the establishment of parallel institutions—that would be used in the Philippines, Latin America, Eastern Europe and elsewhere in subsequent years.Despite the bloody image of the revolution and the authoritarianism and militarism of the Islamic Republic that followed, there was a clear commitment to keeping the actual insurrection unarmed. Protestors were told by the leadership of the resistance to try to win over the troops rather than attack them; indeed, thousands of troops deserted, some in the middle of confrontations with crowds. Clandestinely smuggled audio cassette tapes of Ayatollah Khomeini speaking about the revolution played a key role in the movement’s mass mobilization, and led Abolhassan Sadegh, an official with the Ministry of National Guidance, to note that “tape cassettes are stronger than fighter planes.” Ayatollah Khomeini’s speeches, circulated through such covert methods, emphasized the power of unarmed resistance and noncooperation. In one speech, he said, “The clenched fists of freedom fighters can crush the tanks and guns of the oppressors.” There were few of the violent activities normally associated with armed revolutions such as shooting soldiers, setting fires to government buildings or looting. Such incidents that did occur were unorganized and spontaneous and did not appear to have the support of the leadership of the movement.One element that contributed to people’s willingness to mobilize under harsh repression was the value of martyrdom in Shia Islam. The movement’s emphasis was to “save Islam by our blood.” Indeed, there are interesting parallels between the legacy of martyrdom inspired by early Shia leader Imam Hossein and the Gandhian tradition of self-sacrifice. As demonstrated by their subsequent rule, the Iranian revolution’s leadership clearly did not support nonviolence in principle, but recognized its utilitarian advantages against the well-armed security apparatus of the Shah’s regime.In January 1963, the Shah announced a six-point program of reform called the White Revolution, an American-inspired package of measures designed to give his regime a liberal and progressive facade. Ayatollah Khomeini summoned a meeting of his colleagues in Qom to press upon them the necessity of opposing the Shah's plans. They sent Ayatollah Kamalvand, to see the Shah and gauge his intentions. Although the Shah showed no inclination to retreat or compromise, it took further pressure by Ayatollah Khomeini on the other senior 'ulama' of Qom to persuade them to decree a boycott of the referendum that the Shah had planned to obtain the appearance of popular approval for his White Revolution. Ayatollah Khomeini issued on January 22, 1963 a strongly worded declaration denouncing the Shah and his plans. Two days later Shah took armored column to Qom, and he delivered a speech harshly attacking the 'ulama' as a class.Ayatollah Khomeini continued his denunciation of the Shah's programs, issuing a manifesto that also bore the signatures of eight other senior scholars. In it he listed the various ways in which the Shah had violated the constitution, condemned the spread of moral corruption in the country, and accused the Shah of comprehensive submission to America and Israel. He also decreed that the Norooz celebrations for the Iranian year 1342 (which fell on March 21, 1963) be cancelled as a sign of protest against government policies.On the afternoon of 'Ashoura (June 3, 1963), Imam Khomeini delivered a speech at the Feyziyeh madreseh in which he drew parallels between the Umayyad caliph Yazid and the Shah and warned the Shah that if he did not change his ways the day would come when the people would offer up thanks for his departure from the country. The immediate effect of the Imam's speech was, however, his arrest two days later at 3 o'clock in the morning by a group of commandos who hastily transferred him to the Qasr prison in Tehran. As dawn broke on June 3, the news of his arrest spread first through Qom and then to other cities. In Qom, Tehran, Shiraz, Mashhad and Varamin, masses of angry demonstrators were confronted by tanks and paratroopers. It was not until six days later that order was fully restored. This uprising of 15 Khordad 1342 marked a turning point in Iranian history.

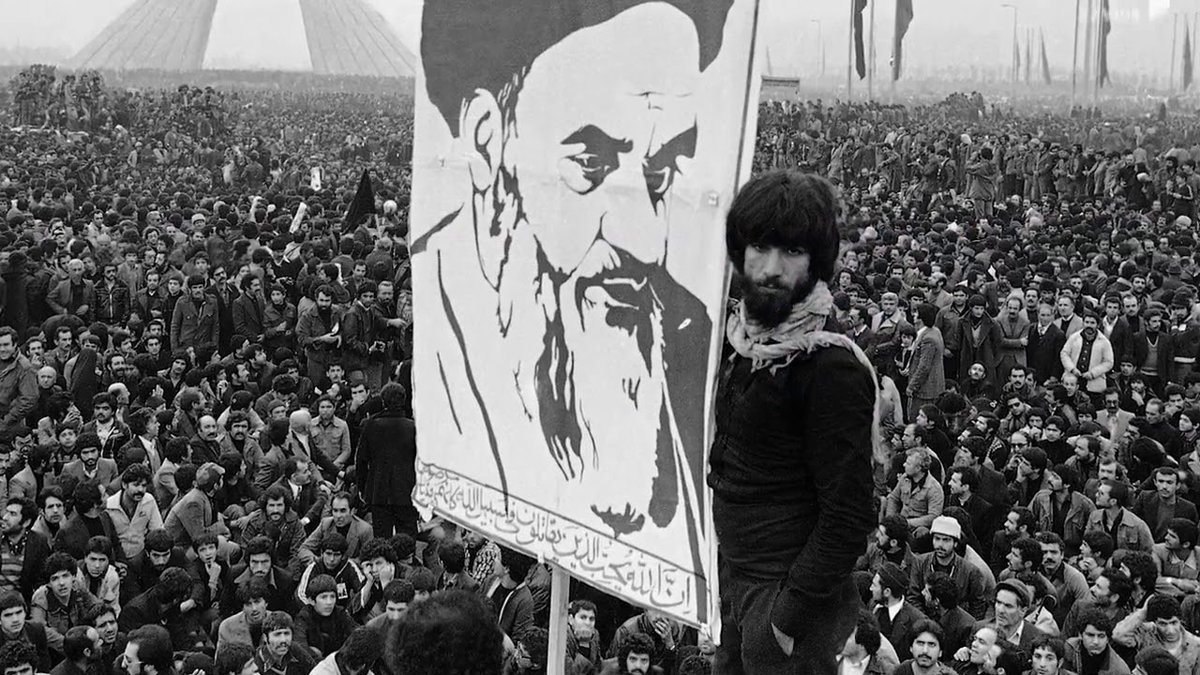

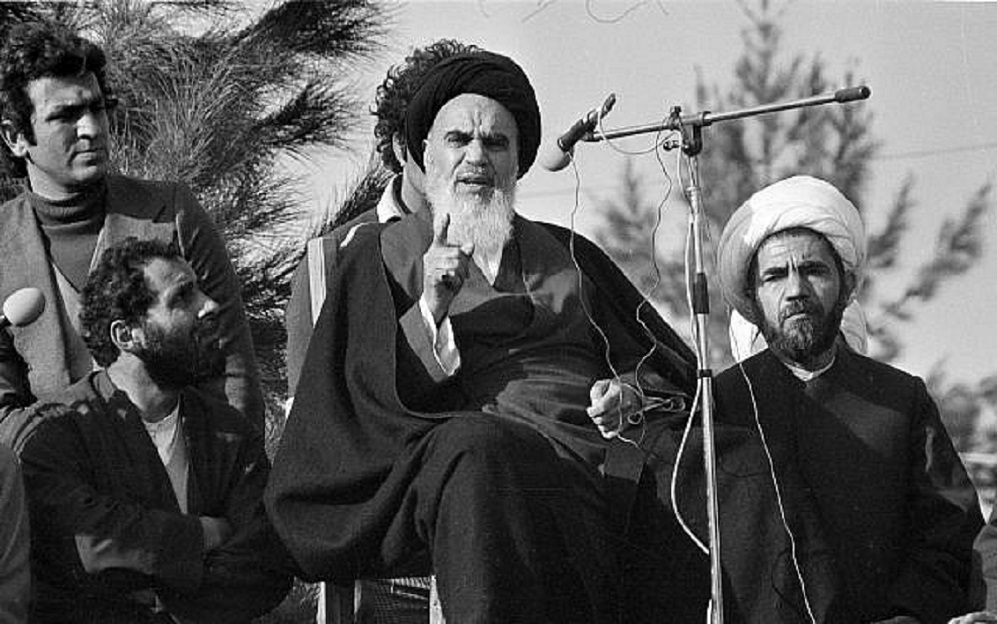

When the secularist and religious opposition came into the streets together, the shah was overwhelmed by the size of the protests. He left the country in January 1979. Khomeini, who had been deported from Iraq, returned to Tehran from Paris on February 1 and was welcomed by a crowd of several million.Khomeini's first move was to reject the reformist prime minister appointed by the fleeing shah. That government collapsed on February 11. Then the ayatollah's clerical supporters set out to take power from the other parties in the revolution.

When the secularist and religious opposition came into the streets together, the shah was overwhelmed by the size of the protests. He left the country in January 1979. Khomeini, who had been deported from Iraq, returned to Tehran from Paris on February 1 and was welcomed by a crowd of several million.Khomeini's first move was to reject the reformist prime minister appointed by the fleeing shah. That government collapsed on February 11. Then the ayatollah's clerical supporters set out to take power from the other parties in the revolution.

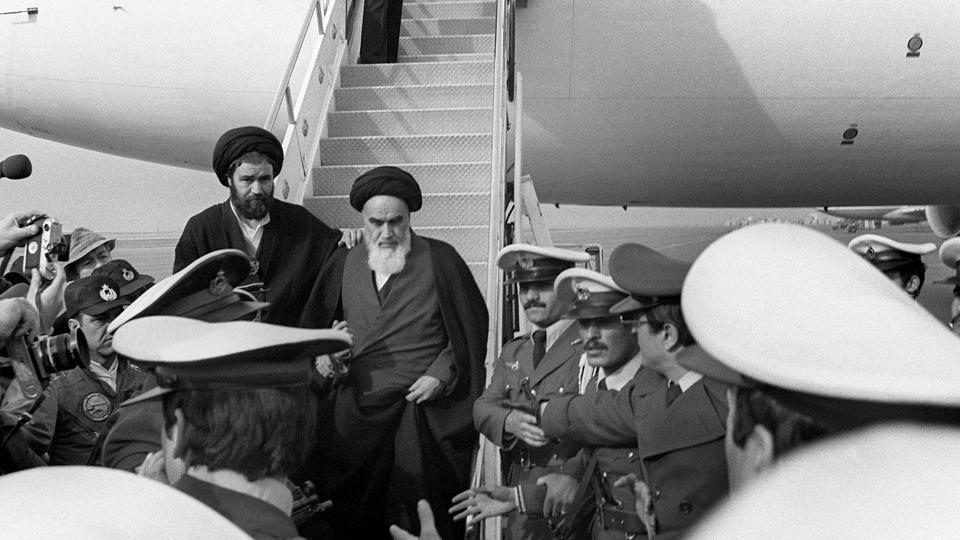

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1900-1989) was born in Kohmeyn in central Iran. He became a religious scholar and in the early 1920s rose to become an 'ayatollah', a term for a leading Shia scholar.In 1962, Khomeini was arrested by the shah's security service for his outspoken opposition to the pro-Western regime of the Shah. His arrest elevated him to the status of national hero. In 1964, he was exiled, living in Turkey, Iraq and then France, from where he urged his supporters to overthrow the shah. By the late 1970s, the shah had become deeply unpopular and there were riots, strikes and mass demonstrations across the country, like all great revolutionaries, mobilized support by articulating a compelling concept. Khomeini's concept of religious political leaders was a surprising innovation in Iran.He argued that only Iran's religious strength could save the country from foreign exploitation and that Islamic law, Shari'a, offered everything necessary for good government and a just society.Specifically, Khomeini argued that full implementation of Shari'a means Islamist jurists should rule the country.During the last few months of his exile, Khomeini received a constant stream of reporters, supporters, and notables, eager to hear the spiritual leader of the revolution. The word of Khomeini’s possible Kashmir ancestry in Reza’s statements spread worldwide and soon, several parts of India emerged with claims of the cleric’s ancestry.Earlier, during his time of exile in Iraq’s holy city of Najaf for more than a decade, Khomeini and Aga Syed Yusuf of Kashmir used to exchange letters and telegrams often. The exchange of letters was rather frequent till Khomeini was exiled from Iraq in 1978 by the then Vice-president Saddam Hussein on the request of the monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, of Iran.According to a statement of Khomeini’s elder brother, Syed Morteza Pasandideh, Khomeini’s grandfather, Syed Ahmad, left Lucknow (his point of departure was Kashmir, not Lucknow) sometime in the middle of the nineteenth century on pilgrimage to the tomb of Hazrat ‘Ali in Najaf. While in Najaf, Syed Ahmad met Yousef Khan, a prominent citizen of Khomeyn. Accepting his invitation, he decided to settle in Khomeyn to assume the responsibility for the religious needs of its citizens and also took Yousef Khan’s daughter in marriage.In March 1903, Khomeini was just 5 months old when he lost his father. And in 1918, Khomeini lost both his aunt, Sahiba, and his mother, Hajar. Responsibility for the family then devolved on his eldest brother, Syed Mourteza, later to be known as Ayatollah Pasandideh.In France, he got the international press coverage that he hadn’t been able to achieve in Iraq or Iran. Hundreds of journalists from all over the world thronged to a suburb of Paris where the biggest stories before Khomeini’s arrival had been car accidents and weather reports. He was named the ‘Man of the Year’ in 1979 by American news magazine Time for his international influence, and described as the “virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture”.During the last few months of his exile, Khomeini received a constant stream of reporters, supporters, and notables, eager to hear the spiritual leader of the revolution. The word of Khomeini’s possible Kashmir ancestry in Reza’s statements spread worldwide and soon, several parts of India emerged with claims of the cleric’s ancestry.Earlier, during his time of exile in Iraq’s holy city of Najaf for more than a decade, Khomeini and Aga Syed Yusuf of Kashmir used to exchange letters and telegrams often. The exchange of letters was rather frequent till Khomeini was exiled from Iraq in 1978 by the then Vice-president Saddam Hussein on the request of the monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, of Iran.When news was heard of Khomeini’s wish to go to Kashmir if denied asylum in France, everyone in the Aga’s family started thronging into action, calling for meetings about what and how the supreme leader should be welcomed. An invite party was to be sent to France to escort the Imam to Kashmir. Meanwhile in Iran, the Islamic revolution was gaining unprecedented momentum, the Shah of Iran was on his heels, time was running out fast, and the preparations for Khomeini’s arrival in Kashmir were taking time.Khomeini had not been allowed to return to Iran during the Shah’s reign (as he had been in exile). On January 17, 1979, the Shah left the country, ostensibly “on vacation”, never to return. Two weeks later, on Thursday, February 1, 1979, Khomeini returned in triumph to Iran, welcomed by a joyous crowd estimated.

Ayatollah Khomeini and his disciples promised paradise, free vehicles, free transport, free utilities, free gasoline and other free goods. Many believed in this but they opened the doors to hell. Today, many regret having taken part in the street demonstrations. The younger generation blame their parents for the current situation in Iran.”The White Revolution’s land reform and emancipation of women were not, in Mohammad Reza’s widow’s opinion, litigious: ‘The majority of the population supported them,” she states. “Obviously big landowners and some religious fanatics didn’t agree with them. The good result out of all this is that today’s Iran does not have a feudal system, despite the pressures of the extremists, and the Islamic Republic did not manage to change the rights of women to vote and to be elected.”

Ayatollah Khomeini and his disciples promised paradise, free vehicles, free transport, free utilities, free gasoline and other free goods. Many believed in this but they opened the doors to hell. Today, many regret having taken part in the street demonstrations. The younger generation blame their parents for the current situation in Iran.”The White Revolution’s land reform and emancipation of women were not, in Mohammad Reza’s widow’s opinion, litigious: ‘The majority of the population supported them,” she states. “Obviously big landowners and some religious fanatics didn’t agree with them. The good result out of all this is that today’s Iran does not have a feudal system, despite the pressures of the extremists, and the Islamic Republic did not manage to change the rights of women to vote and to be elected.”

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi died a king without a throne.In the end, he was a man without a country. Forced to flee the gathering storm of revolution in Iran in January 1979, the shah, his wife, Farah, members of his family and a dwindling retinue of aides and bodyguards moved from one country to another in search of a secure asylum.They went first to Egypt, then to Morocco, the Bahamas and Mexico. On Oct. 22, 1979, he came to the United States for a gall bladder operation and treatment of cancer. Thirteen days later, militant Iranian Moslems invaded the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took Americans there hostage to demand the shah's extradition, the return of his wealth and a U.S. confession of "crimes" in Iran.At the end of the shah's medical treatment in New York, Mexico refused to allow him to return. He went to Panama and then again to Egypt. He died of complications from his cancer treatment at the Maadi Military Hospital in Cairo. He was 60.The downfall of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi resulted from a number of factors. Among them were the way he used his country's fabulous oil wealth, the economic strains and corruption it fostered, the brutalities of his secret police and the repression of political dissent, the imperious personal style he projected.Yet the shah undeniably tried to promote the economic progress of his country and implement social reforms. He used the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 increases that he was instrumental in bringing about to launch a head-long industrialization drive designed to put Iran on a par with the world's most advanced countries in his lifetime.During the shah's reign, Iran made great strides in reducing illiteracy, improving health care, introducing modern technology to the country and generally raising the population's standard of living. His critics have charged that these improvements were not enough and that more could have been accomplished if Iran's oil money had not been misused.The trim, athletic shah also had earned a reputation as a survivor.He had narrowly escaped death in several assassination attempts and plots, walked away from two airplane crashes, and held on to power despite wars, revolutions and coups in neighboring states and serious upheavals in his own country.In 1953, the shah was forced into a brief exile by domestic opponents, and a decade later his regime was rocked by an upheaval against his consolidation of power with a land reform package.The shah contributed to this image because he was so unlike most Iranians and seemed at times even to disdain them. He became a stranger in his own land. He lost touch with his own people.In the last two decades especially, the shah surrounded himself with sycophants who told him mostly what he wanted to hear and reinforced a belief that he only had to give an order and his will would be done.The shah's illusions about the power he wielded were reflected in his often naive economic policies, which fueled the unrest that eventually toppled him.He seemed to believe that he could buck convention, that he could do the impossible by using Iran's huge influx of oil wealth to impose industrialization from the top. He tried to stick multibillion-dollar petrochemical complexes, nuclear power plants and other advanced industrial units into the arid landscape like pins into a map.

TOMB SHAH OF IRAN Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, Farah Diba, wife of the late Shah of Iran, puts her hand on her husband's tomb at the Rifai mosque in Cairo 26 July 2005 marking the 25th anniversary of the death of Shah. Pahlavi died in Egypt in 1980.

TOMB SHAH OF IRAN Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, Farah Diba, wife of the late Shah of Iran, puts her hand on her husband's tomb at the Rifai mosque in Cairo 26 July 2005 marking the 25th anniversary of the death of Shah. Pahlavi died in Egypt in 1980.