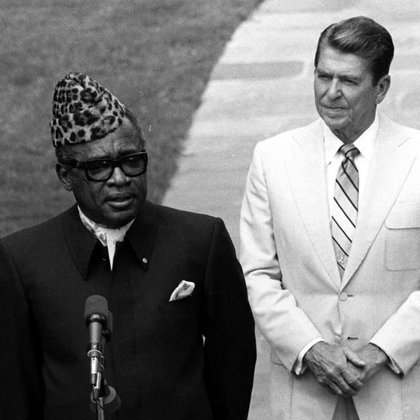

MOBUTU SESE SEKO (1930-1997) WAS THE SECOND PRESIDENT OF THE CONGO (ZAIRE).HE SET UP A DICTATORIAL KLEPTOCRACY 32 YEARS.LAURENT KABILA AND A REBEL ARMY FORCED HIM OUT OF THE COUNTRY AND TOOK POWER,LEAVING HIM IN EXILE IN MOROCCO,WHERE HE DID THREE MONTHS LATER.

The late Zairian President, Mobutu Sese Seko ruled the country known

nowadays as the Democratic Republic of Congo from 1965 to 1997. He is

known for spreading the Mobutism ideology in the country and for

implying a mono party rule.As a soldier, Mobutu developed a passion for literature and started

writing for Actualités Africaines, a magazine set by Belgian colonial.

After his service, he became a full-time journalist for l’avenir, a

daily magazine in Leopoldville. His work in journalism, allowed him to

meet several Congolese intellectuals who dreamt of bringing independence

to the country. At that time, he joined Partice Lumumba’s movement

called MNC, Mouvement National Congolais. He formed a close link with

Lumumba, in 1957 and became his secretary.

The late Zairian President, Mobutu Sese Seko ruled the country known

nowadays as the Democratic Republic of Congo from 1965 to 1997. He is

known for spreading the Mobutism ideology in the country and for

implying a mono party rule.As a soldier, Mobutu developed a passion for literature and started

writing for Actualités Africaines, a magazine set by Belgian colonial.

After his service, he became a full-time journalist for l’avenir, a

daily magazine in Leopoldville. His work in journalism, allowed him to

meet several Congolese intellectuals who dreamt of bringing independence

to the country. At that time, he joined Partice Lumumba’s movement

called MNC, Mouvement National Congolais. He formed a close link with

Lumumba, in 1957 and became his secretary.

Mobutu Sese Seko was born Joseph Désiré Mobutu on Oct. 14, 1930, at Lisala. Although his ascendancy was Ngbandi (a non-Bantu tribe of Sudanese origin), he grew up among the Bantu-speaking riverine peoples of the Congo who are commonly referred to as Bangala. He attended a secondary school run by Catholic missionaries at Coquilhatville (later Mbandaka) and after being dismissed for insubordination was drafted into the Force Publique in 1950. His father was a cook, who died when Mobutu was a child, and his mother was a maid in a hotel. She used her earnings to send him to a Christian Brothers Catholic boarding school for his education. In 1949 he joined the Force Publique, an internal security force of Congolese troops but with Belgian officers, and rose to sergeant. He stayed there for seven years, leaving to become a newspaper reporter. It was in that position that he met Congolese nationalist Patrice Lumumba, and Mobutu was so taken with him that he joined Lumumba's political party, the Congolese National Movement (MNC).The late dictator of the vast African country, renamed Democratic Republic of Congo after his overthrow, is buried in the European cemetery of the Moroccan capital without the fanfare associated with Mobutu during his rule.General Joseph-Desire Mobutu staged a coup in the former Belgian colony in 1965. He renamed the country Zaire and himself Mobutu Sese Seko.The 1994 genocide in Rwanda and the breakdown of order in Burundi that began in 1993 indirectly helped cause Mobutu's final downfall. More than one million refugees fled into Zaire's eastern border regions, unsettling the local population and reviving dormant feuds.Mobutu Sese Seko, Zaire's longtime dictator and the last of a generation of cold war rulers who grew fabulously rich by providing a bulwark against Communism.He built his political longevity on three pillars: violence, cunning and the use of state funds to buy off enemies. His systematic looting of the national treasury and major industries gave birth to the term ''kleptocracy'' to describe a reign of official corruption that reputedly made him one of the world's wealthiest heads of state.With the support of the army he/she took power in September 1960, suspended the Constitution for three months, Lumumba jailed and banned all political activities. It remained the highest judiciary in the country until February 1961, the date on which the Government gave to Kasavubu. Became involved him in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, who disappeared in mysterious circumstances in the province of Katanga. Kasavubu confirmed you as Chief of the General staff, since he/she tried to carry out the modernization and reorganization of the army. It gave a coup in November 1965 with the help of the army, to escalate clashes between supporters between President Kasavubu and Prime Minister Moses Tshombe, after which he/she became the owner of the country. Proclaimed himself President and appointed Prime Minister Leonard Mulamba.Although initially stated that it was only intended to retain power for a period of five years, while he/she considered necessary to restore order in the country, began to take a series of measures to consolidate power. He/She did all the members of the management and the Government to respond directly to him for their actions. It banned political parties and all that to appear contrary to its action was imprisoned or killed. In a decree issued in March 1966 it extended the period of its mandate and assumed all the powers of the Prime Minister, who had ceased. Mobutu founded the Popular Movement of the revolution, which became the only party in the country. In 1967, he/she had to deal with a revolt of the mercenaries who constituted an important group in the Congolese army.Plebiscite in which was the only candidate, confirmed you as President in 1970. He began to establish a sort of cult towards him, and all his actions and words were considered sacred and should be obeyed; Moreover, the decrees of the Government came to refer to him with the nickname of Messiah. In 1971 he started a program in order to Congo what he called African authenticity. Within this plan changed the name of the country, which up to then was called Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zaire, and his Joseph-Desire, by the of Sese Seko ('El Cesar'). In 1973 he/she undertook the nationalization of the main sectors of the Zairean economy, with special attention to the copper mines of Katanga, but the economic crisis in which the country because of this decision, was involved forced him in 1976 to allow the entry of foreign capital.He was confirmed in his post in 1977, but by then the corruption had become an endemic aspect in the Zairean administration, of which the main beneficiary was the own Mobutu, who became one of the biggest fortunes of the country. A new plebiscite, fully rigged, returned to confirm him as President in 1984. With the intention to end the pressures received from the opposition and the international community, it included civilians in some of the main jobs of the Administration and the Government. Despite this, he/she was forced to convene multi-party in 1990 legislative elections, although he/she managed to maintain power. The opposition was gradually creating a series of bodies devoted to unseat Mobutu.The end came in May 1997 when he was toppled by rebel leader Laurent Kabila with the support of Rwanda and Uganda.Because of his educational qualifications, Mobutu was trained as a noncommissioned officer and given a desk job as an accountant. He also tried his hand at journalism by writing a few pieces for army periodicals, and when he left the Force Publique in 1956, he became a stringer and then a regular staffer in Léopoldville, rising to the post of editor of the weekly Actualités Africaines. He received further training at the official Congo Information Office and then at a Brussels school of journalism.

He was installed and supported by the West, mostly Belgium and the US,

because of his strong stance against communism, but once in, the power

apparently went to his head and his regime became notorious for the

usual corruption, human rights abuse and nepotism – and also, in his

case, amassing an enormous personal fortune, partly through embezzlement

of US funds, that led some to nickname his rule a ‘kleptocracy’.

Eventually in 1997, after six years of promising to help stop economic

deterioration and unrest by sharing power with opposition leaders while

at the same time using the army to prevent anything changing.

He was installed and supported by the West, mostly Belgium and the US,

because of his strong stance against communism, but once in, the power

apparently went to his head and his regime became notorious for the

usual corruption, human rights abuse and nepotism – and also, in his

case, amassing an enormous personal fortune, partly through embezzlement

of US funds, that led some to nickname his rule a ‘kleptocracy’.

Eventually in 1997, after six years of promising to help stop economic

deterioration and unrest by sharing power with opposition leaders while

at the same time using the army to prevent anything changing.During that period, Mobutu met Patrice Lumumba and became his representative in Belgium, while reportedly serving as an informer for the Belgian security police. Lumumba brought him back to the Congo in 1960, made him a presidential aide, and raised him to the rank of colonel and chief of staff of the Congolese army.Within 2 months of his appointment, Mobutu used his position to unseat Lumumba and to install the College of Commissioners, made up of graduate students (Sept. 20, 1960). Mobutu consolidated his hold over a segment of the army, particularly over a commando battalion which he organized with the help of a right-wing Moroccan general serving in the UN force, turning it into a praetorian guard to control the capital city. He was instrumental in the decision to turn Lumumba over to the Katanga regime and thus bears a major responsibility for the death of the man who had been his political protector.Thereafter, Mobutu concentrated his efforts on reunifying the fragmented army under his command and even managed to have Moïse Tshombe subscribe to his nominal paramountcy over Katanga forces after securing his release from the brief captivity into which the secessionist leader had allowed himself to be ensnared (June-July 1961).Although civilian rule was officially restored in August 1961 under Premier Cyrille Adoula, Mobutu remained a major power broker. The army's position—and indirectly that of Mobutu—became seriously weakened as a result of its disastrous performance in attempting to control the Congo rebellion in 1963-1965. When Tshombe returned to the Congo as prime minister, Mobutu supported his decision to make use of foreign military support (foreign technicians had in any case been working with the Congolese army since 1960); and he maintained this position when Joseph Kasavubu, sensing international hostility to the presence of white mercenaries in the Congo, announced his intention to dismiss them in October 1965.On Nov. 25, 1965, the army took power (officially for a period of 5 years), and Mobutu became president. Rather than follow Tshombe's policy of open subservience to Western interests, however, Mobutu assumed—at least initially—a nationalistic pose, rehabilitated Lumumba's memory, and challenged Belgian economic control of the Katanga mining industry. His confrontation with the Union Minière eventually led to a face-saving compromise, and his attempts to organize a mass party under the name of MPR (Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution) turned out to be somewhat less than impressive, but he was successful in beating back all attempts to unseat him.Two such attempts (aiming at Tshombe's restoration) took the form of mutiny by Katanga forces and white mercenaries, leading to the latter group's final expulsion from the Congo at the end of 1967. Thereafter, the Mobutu regime gradually inflected its course in a conservative direction (as witnessed by the October 1968 execution of rebel leader Pierre Mulele, who had returned to the Congo following assurances of amnesty) and had to face growing disaffection and unrest on the part of student circles. Diplomatically, Mobutu tried to strengthen the Congo's influence on the African scene. He was consistently favorable to the United States and indeed was often accused of rising to power with CIA help and of being a Trojan horse for American influence in central Africa. In December 1971 he changed his country's name to Zaïre.Like Stalin in the Soviet Union and Saddam Hussein in Iraq, Mobutu consolidated his power by developing a cult of his own personality. Pictures of him were printed by the tens of thousands and sent to every part of the country. His every word was recorded; his was the only official voice to speak for Zaire; orchestrated crowds cheered his speeches; and the Zairian media, all of it state censored, sang his praises and enlarged his stature in an unceasing bombardment. As historian Michael Schatzberg noted, "Scarcely a day passed when the press did not hail even his most banal activities as the magnanimous paternal gestures of a man intent only on the well being of his children, the people of Zaire. Zairian television began its broadcasts with a surrealistic vision of Mobutu descending from the cloud-filled heavens.Mobutu beat back threats from outside Zaire in the 1970s that took the form of invasions from Shaba (formerly Katanga) Province by rebels, some of whom were former Tshombe supporters from the independence era; others were refugees from Mobutu's terror. Mobutu almost lost control of the mining districts for a while in 1978 during a second rebel offensive, and again was forced to offer vocal anti-Communist sentiments in order to obtain aid from American President Jimmy Carter, who was repelled by Mobutu's cynical approach to human rights.Mobutu mishandled his nation's economy almost from the beginning. Once secure in power, he tried to exploit Zaire's natural mineral riches, but he and his backers lacked the personnel, infrastructure, and business ethos to make it work. Even worse, his decision in 1973 to nationalize all other economic assets owned by foreigners led to a catastrophic decline in national productivity and wealth. Humiliated by his financial woes, Mobutu returned farms and factories to their original owners, but a fall in the world price of copper further devasted the Zairian economy.Through the 1980s and into the 1990s, Mobutu grew ever more entrenched and corrupt and ever more suspicious of attempts to liberalize his rule. He made some halfhearted concessions toward free speech and democracy in the early '90s, but was unable to yield any real power.

Laurent Kabila and a rebel army forced him out of the country and took

power, leaving him in exile in Morocco, where he died three months later

from prostate cancer.Laurent Kabila no doubt seemed a much more likely prospect to lead

Zaire, now newly renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo, out of

the dark days of Mobutu’s reign of terror and into the light of the

modern world in, but unfortunately things didn’t work out quite that

way. When the Congo gained independence in June 1960,Kabila was an officer in

the youth wing of the Balubakat (the General Association of the Baluba

People of Katanga), aligned with the first democratically elected

President, Patrice Lumumba.

Laurent Kabila and a rebel army forced him out of the country and took

power, leaving him in exile in Morocco, where he died three months later

from prostate cancer.Laurent Kabila no doubt seemed a much more likely prospect to lead

Zaire, now newly renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo, out of

the dark days of Mobutu’s reign of terror and into the light of the

modern world in, but unfortunately things didn’t work out quite that

way. When the Congo gained independence in June 1960,Kabila was an officer in

the youth wing of the Balubakat (the General Association of the Baluba

People of Katanga), aligned with the first democratically elected

President, Patrice Lumumba.

Another reason that explains the downfall of this strongmen is

related to his made policies towards neighbouring countries, and

especially Rwanda.Mobutu was overthrown in 1997 in a coup led by Joseph Laurent Kabila

encouraged by Rwanda. The ousted president fled the country searching

for exile.He died at the age of 66 in Rabat out of cancer.

Another reason that explains the downfall of this strongmen is

related to his made policies towards neighbouring countries, and

especially Rwanda.Mobutu was overthrown in 1997 in a coup led by Joseph Laurent Kabila

encouraged by Rwanda. The ousted president fled the country searching

for exile.He died at the age of 66 in Rabat out of cancer.