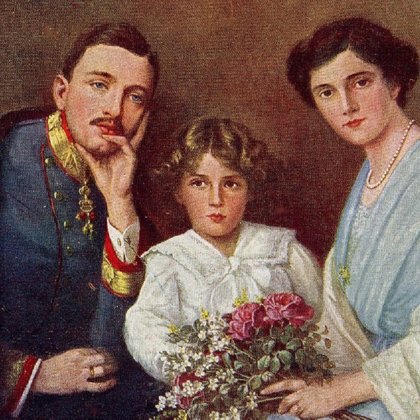

EMPEROR CHARLES I (KARL I)(1887-1922) ,KARL FRANZ JOSEPH LUDWIG HUBERT GEORG OTTO MARIA AND EMPRESS ZITA OF BOURBON - PARMA (1892-1989),THE LAST MONARCH BELONGING TO THE HOUSE OF HABSBURG - LORRAINE BEFORE THE DISSOLUTION OF AUSTRIA - HUNGARY .AFTER HIS UNCLE ARCHDUKE FRANZ FERDINAND OF ASSASSINATED IN 1914.

Emperor Karl is the only decent man to come out of the war in a leadership position, no one listened to him. He sincerely wanted peace, and therefore was despised by the whole world. It was a wonderful chance that was lostBlessed Karl was a happy married man. On his wedding day, he famously declared to his beautiful wife, Zita, “Now we have to help each other to get to heaven!” They were even more devoted to God than to each other and they inscribed their relationship with God into their daily lives together. Blessed Karl proposed to his lovely Zita at the Shrine of Mariazell in Austria and they inscribed a prayer inside their wedding bands, “Sub tuum presidium confugimus, sancta Dei Genitrix” (We fly to take refuge under your protection, O Holy Mother of God). Their love was intense and lasted to the end of Karl’s life. For her part, the Empress Zita never remarried but continued to carry the memory of her husband and she blessed others with the title she had received from him.

Emperor Karl is the only decent man to come out of the war in a leadership position, no one listened to him. He sincerely wanted peace, and therefore was despised by the whole world. It was a wonderful chance that was lostBlessed Karl was a happy married man. On his wedding day, he famously declared to his beautiful wife, Zita, “Now we have to help each other to get to heaven!” They were even more devoted to God than to each other and they inscribed their relationship with God into their daily lives together. Blessed Karl proposed to his lovely Zita at the Shrine of Mariazell in Austria and they inscribed a prayer inside their wedding bands, “Sub tuum presidium confugimus, sancta Dei Genitrix” (We fly to take refuge under your protection, O Holy Mother of God). Their love was intense and lasted to the end of Karl’s life. For her part, the Empress Zita never remarried but continued to carry the memory of her husband and she blessed others with the title she had received from him.Charles I or Karl I (Karl Franz Joseph Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Maria was the last Emperor of Austria, the last King of Hungary;, and the last monarch belonging to the House of Habsburg-Lorraine before the dissolution of Austria-Hungary. After his uncle Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in 1914,he is known to the Catholic Church as Blessed Karl of Austria. He was the last Emperor of Austria, the last King of Hungary (as Charles IV), and the last monarch belonging to the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. After his uncle Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in 1914, Charles became the designated successor of the Emperor Franz Josef. Charles I reigned from 1916 until 1918, when he "renounced participation" in state affairs, but did not abdicate. He spent the remaining years of his life attempting to restore the monarchy until his death in 1922. Following his beatification by the Catholic Church in 2004, within Catholic community he is commonly known as Blessed Karl of Austria.Karl was born on August 17, 1887, at the Castle of Persenbeug in Lower Austria. As he was the great-nephew of the then ruling Emperor, Franz Joseph, it was not envisioned at his birth that it would one day fall to him to rule. Yet, his education prepared him for the task.Charles parents were Archduke Otto Franz of Austria and Princess Maria Josepha of Saxony. At the time, his granduncle Franz Joseph reigned as Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, and his uncle Franz Ferdinand became heir presumptive two years later.That as Emperor he would rule wants to be emphasized. The emperors of the Holy Roman Empire and then the Austro-Hungarian one did not merely reign, like the European monarchs who remain today, all of the “constitutional” ones. By the time of Karl’s accession their power was no longer absolute as it still was with the Russian Tsar, but it was real. None was a figurehead unless rendered so by personal incapacity.As a child, Archduke Charles was reared a devout Roman Catholic. He spent his early years wherever his father's regiment happened to be stationed; later on he lived in Vienna and Reichenau an der Rax. He was privately educated, but, contrary to the custom ruling in the imperial family, he attended a public gymnasium for the sake of demonstrations in scientific subjects. On the conclusion of his studies at the gymnasium, he entered the army, spending the years from 1906 to 1908 as an officer chiefly in Prague, where he studied law and political science concurrently with his military duties.In 1907, he was declared of age and Prince Zdenko Lobkowitz was appointed his chamberlain. In the next few years he carried out his military duties in various Bohemian garrison towns. Charles's relations with his granduncle were not intimate, and those with his uncle Franz Ferdinand were not cordial, with the differences between their wives increasing the existing tension between them. For these reasons, Charles, up to the time of the assassination of his uncle in 1914, obtained no insight into affairs of state, but led the life of a prince not destined for a high political position.Charles became heir presumptive after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, the event which precipitated World War I. Only at this time did the old Emperor take steps to initiate the heir-presumptive to his crown in affairs of state. But the outbreak of World War I interfered with this political education. Charles spent his time during the first phase of the war at headquarters at Teschen, but exercised no military influence.Charles then became a Feldmarschall (Field Marshal) in the Austro-Hungarian Army. In the spring of 1916, in connection with the offensive against Italy, he was entrusted with the command of the XX. Corps, whose affections the heir-presumptive to the throne won by his affability and friendliness. The offensive, after a successful start, soon came to a standstill. Shortly afterwards, Charles went to the eastCharles succeeded to the thrones in November 1916, after the death of his grand-uncle, Emperor Franz Joseph.On 2 December 1916, he assumed the title of Supreme Commander of the whole army from Archduke Friedrich. His coronation as King of Hungary occurred on 30 December. In 1917, Charles secretly entered into peace negotiations with France. He employed his brother-in-law, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, an officer in the Belgian Army, as intermediary. However, the Allies insisted on Austrian recognition of Italian claims to territory and Charles refused, so no progress was made.Although his foreign minister, Graf Czernin, was only interested in negotiating a general peace which would include Germany, Charles himself went much further in suggesting his willingness to make a separate peace. When news of the overture leaked in April 1918, Charles denied involvement until French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau published letters signed by him. This led to Czernin's resignation, forcing Austria-Hungary into an even more dependent position with respect to its seemingly wronged German ally.The Austro-Hungarian Empire was wracked by inner turmoil in the final years of the war, with much tension between ethnic groups. As part of his Fourteen Points, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson demanded that the Empire allow for autonomy and self-determination of its peoples. In response, Charles agreed to reconvene the Imperial Parliament and allow for the creation of a confederation with each national group exercising self-governance. However, the ethnic groups fought for full autonomy as separate nations, as they were now determined to become independent from Vienna at the earliest possible moment.Foreign minister Baron Istvan Burián asked for an armistice 14 October based on the Fourteen Points, and two days later Charles issued a proclamation that radically changed the nature of the Austrian state. The Poles were granted full independence with the purpose of joining their ethnic brethren in Russia and Germany in a Polish state. The rest of the Austrian lands were transformed into a federal union composed of four parts: German, Czech, South Slav, and Ukrainian. Each of the four parts was to be governed by a federal council, and Trieste was to have a special status. However, Secretary of State Robert Lansing replied four days later that the Allies were now committed to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs. Therefore, autonomy for the nationalities was no longer enough. In fact, a Czechoslovak provisional government had joined the Allies 14 October, and the South Slav national council declared an independent South Slav state 29 October 1918.ern front as commander of an army operating against the Russians and Romanians.

Karl grew up imbued with a deep personal trust in God and equipped with all the Catholic moral principles whose political application he would combine, as Emperor, with his appreciation for the Church’s social doctrine. He came to the throne in 1916 due to a series of tragic events: the death at Mayerling (some say by suicide and others by assassination) of Franz Joseph’s only son, Archduke Rudolph; the early death of his own father, Otto, in 1906; and the assassination of his uncle Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo in 1914.As soon as he succeeded to the throne, Ven. Emperor Karl bent his energies to seeking the end of the carnage of World War I, which had been raging for two years. To that purpose he authorized a brother-in-law, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, an officer in the Belgian army, to deliver a set of peace proposals to President Poincare of France. As testimony to the sincerity of his effort, the Emperor stipulated his readiness to sacrifice his hereditary claim to Lorraine and to cede to Italy the Italian ethnic portion of the Trentino, even though Austrian troops at the moment were well advanced into the northern part of the Italian boot. In a Peace Note of August 1, 1917, Pope Benedict XV seconded Karl’s initiative. Both the Pope and Emperor foresaw that unless the war was quickly ended, the unstable Kerensky government that had taken power in Russia in March, 1917, could degenerate into something far worse because it would be far more threatening than imperial Russia ever was to what remained of Western Christendom. This is to speak of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in terms of what it was: the last Catholic world power.Unfortunately, Austria’s Western enemies of the moment, who were looking for U.S. intervention to enable them to achieve territorial and other ambitions, were not ready for peace. At the same time Karl’s own ally, the Prussian Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, hoped to beat England and France on the Western Front before effective U.S. aid could arrive. The war continued.It produced great deprivations on the home front. The poor were especially hard hit. In his capital of Vienna, Karl ordered that carriages and coaches of the imperial court be used to deliver coal to them. Further, he established a new Ministry of Social Welfare in his cabinet and gave its portfolio to the redoubtable Msgr. Ignaz Seipel, an apostle of reforms based on Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum and other papal social encyclicals. Karl also acted to restructure the Empire politically along federalist lines. Establishment of a kind of United States of Greater Austria was his aim. In a manifesto of October 16, 1918, he ordered each ethnic group in the Imperial Parliament to caucus and draw up a plan for the government of its portion of the Empire. These were excellent and desirable moves. However, powerful forces were working against Karl, forces within the West itself, forces which had their agents even inside the Empire.Since the beginning of his rule he favored the creation of third Croatian political entity, in his Croatian Coronation oath from 1916 he recognized the union of the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia with Rijeka and during his short reign supported trialist suggestions from the Croatian Sabor and Ban, but the suggestions were always vetoed by the Hungarian side which did not want to share power with other nations. After Emperor Karl's manifesto of 14 October 1918 was rejected by the declaration of the National Council in Zagreb. President of the Croatian pro-monarchy political party Pure Party of Rights Dr. Aleksandar Horvat, with other parliament members and generals went to visit the emperor on 21 October 1918 in Bad Ischl, where the emperor agreed and signed the trialist manifest under the proposed terms set by the delegation, on the condition that the Hungarian part does the same since he swore an oath on the integrity of the Hungarian crown. The delegation went the next day to Budapest where it presented the manifest to Hungarian officials and Council of Ministers who signed the manifest and released the king from his oath, creating a third Croatian political entity (Zvonimir's kingdom) After the signing, two parades were held in Zagreb, one for the ending of the K.u.K. monarchy, which was held in front of the Croatian National Theater, and another one for saving the trialist monarchy. The last vote for the support of the trialist reorganization of the empire was, however, too late. On 29 October 1918, the Croatian Sabor (parliament) ended the union and all ties with Hungary and Austria, proclaimed the unification of all Croatian lands and entered the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The curiosity is that no act of Sabor dethroned King Karl IV, nor did it acknowledge the entering in a state union with Serbia, which is today mentioned in the preamble of the Constitution of Croatia.A Council of Allied and Successor States Ambassadors assembled to decide the fate of the imperial couple. Extreme opinion called for the imprisonment of Karl as a “war criminal.” However, all his life he had been plagued by weak lungs that made him susceptible to pneumonia, and the infirmity was not overlooked by the All-Seeing Eye. Thus, a subtle, more permanent solution to the “Habsburg problem” was crafted. Karl and Zita were exiled to the damp and rainy island of Madeira. Marooned there without any funds on November 19, 1921, they had to accept the offer of a local banker who gave them the use of his unheated summer home 2,000 feet in the mountains. There was fungus growing on the humid walls.The couple’s gloom was somewhat dispelled by the arrival of their children, but in March, 1922, a dense fog and deep chill caused the Emperor to catch a bad cold. There was no money to summon a doctor and the cold developed into a fatal case of pneumonia.As Karl’s end approached, he placed himself with complete resignation into the hands of Our Lord. His eldest son and heir, Archduke Otto, was brought to the side of the deathbed so that as future head of the House of Habsburg he might learn, in Karl’s words, “how one behaves in such circumstances as a Catholic and as an Emperor.”the Emperor’s life and time as a ruler, as they have here been sketched, that recommends canonization.First, he was a champion of peace and reconciliation. His statesmanship in seeking an honorable peace to end World War I provides a model for political leaders today who do not scruple to wage war even in “anticipatory self-defense.” His deathbed forgiveness of his enemies, including the Masons, challenges the many forms of hatred that abound today. His example is instructive to the public as well as to leaders.Second, he was a champion of social justice. Influenced by Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, he established a Ministry of Social Welfare to implement the Church’s social doctrine. His personal commitment to social justice is shown by his use of his carriages and coaches to transport coal to the poor during the war. His implementation of the papal social encyclicals sets an example for public officials looking to solve today’s economic and social problems.Third, he was a champion of Austro-Slavonic unity and minority ethnic rights. Foreseeing Russian domination of the smaller Slavonic and other ethnic nations sandwiched between the Russian and Prussian Empires, Karl strove to transform his own centralized Empire into a confederation of individual ethnic nations, each having internal autonomy, but with their security and other benefits provided by a united defense, a common market, economic and financial union and foreign policy. Had he succeeded, both Hitler and Stalin would have been blocked.

The family's first home in exile was Wartegg Castle in Rorschach, Switzerland, a property owned by the Bourbon-Parmas. However, the Swiss authorities, worried about the implication of the Habsburgs living near the Austrian border, compelled them to move to the western part of the country. The next month, therefore, found them moving to Villa Prangins, near Lake Geneva, where they resumed a quiet family life. This abruptly ended in March 1920 when, after a period of instability in Hungary, Miklós Horthy was elected regent. Charles was still technically King (as Charles IV) but Horthy sent an emissary to Prangins advising him not to go to Hungary until the situation had calmed. After the Trianon Treaty Horthy's ambition soon grew. Charles became concerned and requested the help of Colonel Strutt to get him into Hungary. Charles twice attempted to regain control, once in March 1921 and again in October 1921. Both attempts failed, despite Zita's staunch support (she insisted on travelling with him on the final dramatic train journey to Budapest.

The family's first home in exile was Wartegg Castle in Rorschach, Switzerland, a property owned by the Bourbon-Parmas. However, the Swiss authorities, worried about the implication of the Habsburgs living near the Austrian border, compelled them to move to the western part of the country. The next month, therefore, found them moving to Villa Prangins, near Lake Geneva, where they resumed a quiet family life. This abruptly ended in March 1920 when, after a period of instability in Hungary, Miklós Horthy was elected regent. Charles was still technically King (as Charles IV) but Horthy sent an emissary to Prangins advising him not to go to Hungary until the situation had calmed. After the Trianon Treaty Horthy's ambition soon grew. Charles became concerned and requested the help of Colonel Strutt to get him into Hungary. Charles twice attempted to regain control, once in March 1921 and again in October 1921. Both attempts failed, despite Zita's staunch support (she insisted on travelling with him on the final dramatic train journey to Budapest.Zita of Bourbon-Parma (Zita Maria delle Grazie Adelgonda Micaela Raffaela Gabriella Giuseppina Antonia Luisa Agnese; 9 May 1892 – 14 March 1989) was the wife of Emperor Charles of Austria. As such, she was the last Empress of Austria, Queen of Hungary, and Queen of Bohemia.Born as the seventeenth child of the dispossessed Robert I, Duke of Parma and his second wife Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal, Zita married the then Archduke Charles of Austria in 1911. Charles became heir presumptive to the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria in 1914 after the assassination of his uncle Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, and acceded to the throne in 1916 after the old emperor's death.After the end of World War I in 1918, the Habsburgs were deposed when the new countries of Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs were formed. Charles and Zita left for exile in Switzerland and later Madeira, where Charles died in 1922. After her husband's death, Zita and her son Otto served as the symbols of unity for the exiled dynasty. A devout Catholic, she raised a large family after being widowed at the age of 29, and never remarried.Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma was born at the Villa Pianore in the Italian Province of Lucca, 9 May 1892. The unusual name Zita was given her after a popular Italian Saint who had lived in Tuscany in the 13th century. She was the third daughter and fifth child of the deposed Robert I, Duke of Parma and his second wife, Maria Antonia of Portugal, a daughter of king Miguel of Portugal and Adelaide of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg. Zita's father had lost his throne as a result of the movement for Italian unification in 1859 when he was still a child. He fathered twelve children during his first marriage to Maria Pia of the Two Sicilies (six of whom were mentally retarded, and three of whom died young). Duke Robert became a widower in 1882, and two years later he married Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal, Zita's mother. The second marriage produced a further twelve children. Zita was the 17th child among Duke Robert's 24 children. Robert moved his large family between Villa Pianore (a large property located between Pietrasanta and Viareggio) and his castle in Schwarzau in lower Austria. It was mainly in these two residences that Zita spent her formative years. The family spent most of the year in Austria moving to Pianore in the Winter and returning in the Summer. To move between them, they took a special train with sixteen coaches to accommodate the family and their belongings.Zita and her siblings were raised to speak Italian, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese and English. She recalled, "We grew up internationally. My father thought of himself first and foremost as a Frenchman, and spent a few weeks every year with the elder children at Chambord, his main property on the Loire. I once asked him how we should describe ourselves. He replied, 'We are French princes who reigned in Italy.' In fact, of the twenty-four children only three including me, were actually born in Italy.At the age of ten, Zita was sent to a boarding school at Zanberg in Upper Bavaria, where there was a strict regime of study and religious instruction. She was summoned home in the autumn of 1907 at the death of her father. Her maternal grandmother sent Zita and her sister Franziska to a convent on the Isle of Wight to complete her education. Brought up as devout Catholics, the Parma children regularly undertook good works for the poor. In Schwarzau the family turned surplus cloth into clothes. Zita and Franziska personally distributed food, clothing, and medicines to the needy in Pianore. Three of Zita's sisters became nuns and, for a time, she considered following the same path. Zita went through a patch of poor health and was sent for the traditional cure at a European spa for two years.

She was born on May 9, 1892, the 17th child of Roberto I, Duke of Parma. in Lucca, Italy. Named after a famous Tuscan saint she was only a child when the unification of Italy dethroned the House of Bourbon-Parma and she grew up moving between family homes in Lucca and Lower Austria. Being from a French royal family, reigning in Italy and forced to spend alot of time on the move they were a very international group and Princess Zita grew up speaking Italian, French, Spanish, German, Portuguese and English. Like all her siblings she was given a strict religious education and was raised to be a devout Catholic where regular charitable work was a family tradition. It was this quality which particularly impressed the young Austrian Archduke Charles who she met during stays in Lower Austria. Charles was smitten right away but for Zita the relationship grew over time before the Archduke proposed for fear she might be married to someone else if he did not act quickly.On October 21, 1911 Charles and Zita were married with the full approval of Emperor Francis Joseph I. Over the years the couple had eight children and it was a very happy marriage and a very close and happy family. They shared a love of simple pleasures, family life and devout faith. It came as a great shock in 1914 when the murder of Archduke Francis Ferdinand suddenly made Zita wife of the heir to the Austrian-Hungarian throne. Soon after World War I broke out and Charles, a general in the Austrian army, was called to the front. Archduchess Zita was very sorrowful about the war, both because of the risks to her husband, her dislike of Austria's German allies and the fact that her family was split by the hostilities; some fighting in the Austrian army and others (denied permission to fight for France) serving in the Belgian army. When Italy entered the war against the Central Powers some in Austria became suspicious of their Italian archduchess. However, the Emperor was very kind to her, brought her and the children to the palace at Schoenbrunn and often confided in her about his thoughts, concerns and worries about the war and the national situation.n the close vicinity of Schwarzau castle was the Villa Wartholz, residence of Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria, Zita’s maternal aunt. She was the stepmother of Archduke Otto, who died in 1906, and the step-grandmother of Archduke Charles of Austria-Este, at that time second-in-line to the Austrian throne. The two daughters of Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria were Zita’s first cousins and Charles’ half-aunts. They had met as children but did not see one another for almost ten years, as each pursued their education. In 1909, his Dragoon regiment was stationed at Brandeis an der Elbe (Brandýs on the Elbe), from where he visited his aunt at Franzensbad. It was during one of these visits that Charles and Zita became reacquainted. Charles was under pressure to marry (Franz Ferdinand, his uncle and first-in-line, had married morganatically, and his children were excluded from the throne) and Zita had a suitably royal genealogy. Zita later recalled, "We were of course glad to meet again and became close friends. On my side feelings developed gradually over the next two years. He seemed to have made his mind up much more quickly, however, and became even more keen when, in the autumn of 1910, rumours spread about that I had got engaged to a distant Spanish relative, Don Jaime, the Duke of Madrid. On hearing this, the Archduke came down post haste from his regiment at Brandeis and sought out his grandmother, Archduchess Maria Theresa, who was also my aunt and the natural confidante in such matters. He asked if the rumor was true and when told it was not, he replied, 'Well, I had better hurry in any case or she will get engaged to someone else.'"Archduke Charles traveled to Villa Pianore and asked for Zita’s hand and, on 13 June 1911, their engagement was announced at the Austrian court. Zita in later years recalled that after her engagement she had expressed to Charles her worries about the fate of the Austrian Empire and the challenges of the monarchy. Charles and Zita were married at the Schwarzau castle on 21 October 1911. Charles's great-uncle, the 81-year-old Emperor Franz Joseph, attended the wedding. He was relieved to see an heir make a suitable marriage, and was in good spirits, even leading the toast at the wedding breakfast. Archduchess Zita soon conceived a son, and Otto was born 20 November 1912. Seven more children would follow in the next decade.In 1916, when Francis Joseph died, Zita became the last Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary. She was very involved in national issues and was constantly at her husband's side. When they had to be apart Charles called her several times a day. She also played a major part in 1917 in the effort to make peace. Working secretly through her brother Prince Sixtus, an officer in the Belgian army, messages were sent via Switzerland to try to negotiate a seperate peace between Austria and France. Empress Zita also used her influence to stop a German plan to bomb the residence of the Belgian King and Queen. Unfortunately, the peace efforts went nowhere. King Albert I of the Belgians was in favor but the French and British were not and while Emperor Charles was in favor the Germans were not. The situation became worse when the Allies made the negotiations public which greatly endangered Austria and Charles and Zita in particular. There had never been any love lost between them and the Germans and the news that they had attempted a seperate peace brought threats of a German takeover of Austria.By the fall of the next year Austria-Hungary was coming apart and Charles and Zita and their family were forced to flee the country to Switzerland. Zita was a great source of strength and comfort to her husband in these hard times and the strain on her had to be great. In 1920 she showed again what she was made of when she accompanied Charles in his effort to regain his throne in Hungary. After both attempts failed the family eventually settled on the Portuguese island of Madeira where Charles died not long after. Empress Zita carried on with the same grace and dignity she always showed, raising her children in royal fashion and never giving up hope for a Hapsburg restoration. The family moved to Spain and later to Belgium. When Engelbert Dollfuss became chancellor of Austria the possibility of a restoration seemed good but all hopes were ended when Dollfuss was assassinated and Austria was occupied by Germany. World War II and the invasion of Belgium forced the family to flee to the United States where two of her sons joined the American army. Empress Zita contributed by raising money in the US and Canada. In 1982 she was finally allowed to return to Austria where she died, still loved and respected by all, in 1989 at the age of 96.

On 11 November 1918, the same day as the armistice ending the war between the Allied Powers and Germany was signed, Charles issued a carefully worded proclamation in which he recognized the Austrian people's right to determine the form of the state and "relinquish(ed) every participation in the administration of the State." He also released his officials from their oath of loyalty to him. On the same day the Imperial Family left Schönbrunn Palace and moved to Castle Eckartsau, east of Vienna. On 13 November, following a visit of Hungarian magnates, Charles issued a similar proclamation for Hungary.Although it has widely been cited as an "abdication", that word was never mentioned in either proclamation. Indeed, he deliberately avoided using the word abdication in the hope that the people of either Austria or Hungary would vote to recall him.Instead, on 12 November, the day after he issued his proclamation, the independent Republic of German-Austria was proclaimed, followed by the proclamation of the Hungarian Democratic Republic on 16 November. An uneasy truce-like situation ensued and persisted until 23–24 March 1919, when Charles left for Switzerland, escorted by the commander of the small British guard detachment at Eckartsau, Lt. Col. Edward Lisle Strutt. As the Imperial Train left Austria on 24 March, Charles issued another proclamation in which he confirmed his claim of sovereignty, declaring that "whatever the national assembly of German Austria has resolved with respect to these matters since 11 November is null and void for me and my House."Although the newly established republican government of Austria was not aware of this "Manifesto of Feldkirch" at this time (it had been dispatched only to the Spanish King Alfonso XIII and to Pope Benedict XV through diplomatic channels), the politicians now in power were extremely irritated by the Emperor's departure without an explicit abdication. The Austrian Parliament passed the Habsburg Law on 3 April 1919, which permanently barred Charles from returning to Austria. Other Habsburgs were banished from Austrian territory unless they renounced all intentions of reclaiming the throne and accepted the status of ordinary citizens. Another law, passed on the same day, abolished all nobility in Austria.In Switzerland, Charles and his family briefly took residence at Castle Wartegg near Rorschach at Lake Constance and later moved to Château de Prangins at Lake Geneva on 20 May 1919.Encouraged by Hungarian royalists ("legitimists"), Charles sought twice in 1921 to reclaim the throne of Hungary, but failed largely because Hungary's regent, Admiral Miklós Horthy (the last commander of the Imperial and Royal Navy), refused to support him. Horthy's failure to support Charles' restoration attempts is often described as "treasonous" by royalists. Critics suggest that Horthy's actions were more firmly grounded in political reality than those of Charles and his supporters. Indeed, the neighbouring countries had threatened to invade Hungary if Charles tried to regain the throne. Later in 1921, the Hungarian parliament formally nullified the Pragmatic Sanction, an act that effectively dethroned the Habsburgs.After the second failed attempt at restoration in Hungary, Charles and his pregnant wife Zita were briefly quarantined at Tihany Abbey. On 1 November 1921 they were taken to the Hungarian Danube harbour city of Baja, were made to board the British monitor HMS Glowworm and there removed to the Black Sea where they were transferred to the light cruiser HMS Cardiff. They arrived at their final exile, the Portuguese island of Madeira, on 19 November 1921. Determined to prevent a third restoration attempt, the Council of Allied Powers had agreed on Madeira because it was isolated in the Atlantic and easily guarded.Originally the couple and their children, who joined them on 2 February 1922, lived at Funchal at the Villa Vittoria, next to Reid's Hotel and later moved to Quinta do Monte. Compared to the imperial glory in Vienna and even at Eckartsau, conditions there were certainly impoverished.Charles did not leave Madeira again. On 9 March 1922 he had caught a cold in town, which developed into bronchitis and subsequently progressed to severe pneumonia. Having suffered two heart attacks, he died of respiratory failure on 1 April, in the presence of his wife (who was pregnant with their eighth child) and nine-year-old Crown Prince Otto, remaining conscious almost until his last moments. His last words to his wife were "I love you so much." His remains except for his heart are still interred on the island, in the Church of Our Lady of Monte (Igreja de Nossa Senhora do Monte), in spite of several attempts to move them to the Habsburg Crypt in Vienna. His heart and the heart of his wife are entombed in Muri Abbey, Switzerland.Karl was a great leader, a Prince of peace, who wanted to save the world from a year of war; a statesman with ideas to save his people from the complicated problems of his Empire; a King who loved his people, a fearless man, a noble soul, distinguished, a saint from whose grave blessings come."Furthermore, Anatole France, the French novelist, stated:"Emperor Karl is the only decent man to come out of the war in a leadership position, no one listened to him. He sincerely wanted peace, and therefore was despised by the whole world. It was a wonderful chance that was lostBlessed Karl was a happy married man. On his wedding day, he famously declared to his beautiful wife, Zita, “Now we have to help each other to get to heaven!” They were even more devoted to God than to each other and they inscribed their relationship with God into their daily lives together. Blessed Karl proposed to his lovely Zita at the Shrine of Mariazell in Austria and they inscribed a prayer inside their wedding bands, “Sub tuum presidium confugimus, sancta Dei Genitrix” (We fly to take refuge under your protection, O Holy Mother of God). Their love was intense and lasted to the end of Karl’s life. For her part, the Empress Zita never remarried but continued to carry the memory of her husband and she blessed others with the title she had received from him.Charles and Zita were crowned in Budapest on 30 December 1916. Following the coronation there was a banquet, but after that the festivities ended, as the emperor and empress thought it wrong to have prolonged celebrations during a time of war. At the beginning of the reign, Charles was more often than not away from Vienna, so he had a telephone line installed from Baden (where Charles's military headquarters were located) to the Hofburg. He called Zita several times a day whenever they were separated. Zita had some influence on her husband and would discreetly attend audiences with the Prime Minister or military briefings, and she had a special interest in social policy. However, military matters were the sole domain of Charles. Energetic and strong-willed, Zita accompanied her husband to the provinces and to the front, as well as occupying herself with charitable works and hospital visits to the war-wounded.By this time, the war was closing in on the embattled Emperor. A Union of Czech Deputies had already sworn an oath to a new Czechoslovak state independent of the Habsburg Empire on 13 April 1918, the prestige of the German Army had taken a severe blow at the Battle of Amiens, and, on 25 September 1918, King Ferdinand of Bulgaria broke away from his allies in the Central Powers and sued for peace independently. Zita was with Charles when he received the telegram of Bulgaria's collapse. She remembered it "made it even more urgent to start peace talks with the Western Powers while there was still something to talk about. On 16 October, the emperor issued a "People's Manifesto" proposing the empire be restructured on federal lines with each nationality gaining its own state. Instead, each nation broke away and the empire effectively dissolved.Leaving behind their children at Gödöllő, Charles and Zita travelled to the Schönbrunn Palace. By this time ministers had been appointed by the new state of "German-Austria", and by 11 November, together with the emperor's spokesmen, they prepared a manifesto for Charles to sign. Zita, at first glance, mistook it for an abdication and made her famous statement "A sovereign can never abdicate. He can be deposed... All right. That is force. But abdicate — never, never, never! I would rather fall here at your side. Then there would be Otto. And even if all of us here were killed, there would still be other Habsburgs!" Charles gave his permission for the document to be published, and he, his family and the remnants of his Court departed for the Royal shooting lodge at Eckartsau, close to the borders with Hungary and Slovakia. The Republic of German-Austria was pronounced the next day.The family's first home in exile was Wartegg Castle in Rorschach, Switzerland, a property owned by the Bourbon-Parmas. However, the Swiss authorities, worried about the implication of the Habsburgs living near the Austrian border, compelled them to move to the western part of the country. The next month, therefore, found them moving to Villa Prangins, near Lake Geneva, where they resumed a quiet family life. This abruptly ended in March 1920 when, after a period of instability in Hungary, Miklós Horthy was elected regent. Charles was still technically King (as Charles IV) but Horthy sent an emissary to Prangins advising him not to go to Hungary until the situation had calmed. After the Trianon Treaty Horthy's ambition soon grew. Charles became concerned and requested the help of Colonel Strutt to get him into Hungary. Charles twice attempted to regain control, once in March 1921 and again in October 1921. Both attempts failed, despite Zita's staunch support (she insisted on travelling with him on the final dramatic train journey to Budapest).Charles and Zita temporarily resided at Castle Tata, the home of Count Esterházy, until a suitable permanent exile could be found. Malta was mooted as a possibility, but was declined by Lord Curzon, and French territory was ruled out due to the possibility of Zita's brothers intriguing on Charles's behalf. Eventually, the Portuguese island of Madeira was chosen. On 31 October 1921, the former Imperial couple were taken by rail from Tihany to Baja, where the Royal Navy monitor HMS Glowworm was waiting. They finally arrived at Funchal on 19 November. Their children were being looked after at Wartegg Castle in Switzerland by Charles's step-grandmother Maria Theresa, although Zita managed to see them in Zurich when her son Robert needed an operation for appendicitis. The children joined their parents in Madeira in February 1922.