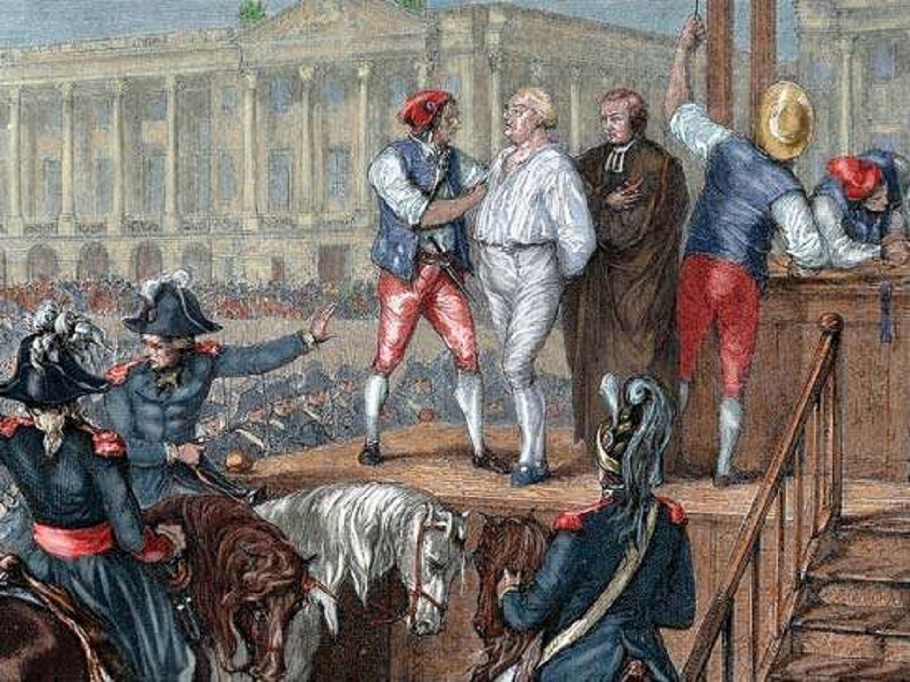

LOUIS XVI WAS KING OF FRANCE (1715 - 1774),HE WAS NICKNAMED" THE WELL - BELOVED " BUT HIS FAILURES CONTRIBUTED TO THE CRISIS THAT BROUGHT ON FRENCH REVOLUTION.FRENCH REVOLUTION, BEHEADED OF KING LOUIS XVI AND HIS WIFE MARIE ANTOINETTE.SHE WAS AN AUSTRIAN PRINCES OF THE HABSBURG DINASTY.

Louis XVI was the third son of Louis, Dauphin of France and grandson of Louis XV of France. His mother, Marie-Josephe of Saxony, was the daughter of Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, also the King of Poland.Starting at the age of 4, his reign of 72 years and 110 days is the longest recorded of any monarch of a sovereign country in European history. Louis XVI’s great-great-great grandfather was Louis XIV of France (also known as the “Sun King”).When Louis XVI acceded to the throne in 1774, he was nineteen years old. He had an enormous responsibility, as the government was deeply in debt, and resentment of "despotic" monarchy was on the rise. He himself felt woefully unqualified to resolve the situation.

Louis XVI was the third son of Louis, Dauphin of France and grandson of Louis XV of France. His mother, Marie-Josephe of Saxony, was the daughter of Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, also the King of Poland.Starting at the age of 4, his reign of 72 years and 110 days is the longest recorded of any monarch of a sovereign country in European history. Louis XVI’s great-great-great grandfather was Louis XIV of France (also known as the “Sun King”).When Louis XVI acceded to the throne in 1774, he was nineteen years old. He had an enormous responsibility, as the government was deeply in debt, and resentment of "despotic" monarchy was on the rise. He himself felt woefully unqualified to resolve the situation.

Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna was born in Vienna, the beautiful daughter of Emperor Francis I. Unlike Louis-Auguste, who had a rather austere upbringing, she was a very social child with a close family and many friends. She liked playing music and dancing and was reportedly very talented at both. Her mother Maria Theresa, acting as queen after the death of the emperor, planned to unite Austria with its former enemy France through marriage. Most likely, Antonia would not have been selected to fulfill this duty, but her older, eligible sisters had died from an outbreak of smallpox. Not yet 12 years old, she was promised to the future king of France.

Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna was born in Vienna, the beautiful daughter of Emperor Francis I. Unlike Louis-Auguste, who had a rather austere upbringing, she was a very social child with a close family and many friends. She liked playing music and dancing and was reportedly very talented at both. Her mother Maria Theresa, acting as queen after the death of the emperor, planned to unite Austria with its former enemy France through marriage. Most likely, Antonia would not have been selected to fulfill this duty, but her older, eligible sisters had died from an outbreak of smallpox. Not yet 12 years old, she was promised to the future king of France.

Louis XVI was the grandson of Louis XV. He became Dauphin in 1765 and inherited the throne in 1774 at the age of 20. His governor, the Duc de La Vauguyon, provided him with a well-rounded education but singularly failed to prepare the young prince for the concrete challenges of government. This lack of preparation was compounded by the fact that he was only the third royal son and did not become heir apparent until after the death of his two elder brothers. The future Louis XVI studied history, geography, science, law, Latin and Greek as well as various modern languages. His political philosophy was influenced by Fénelon and the thinkers of the Enlightenment, who held that the nation existed independently of the king – an idea which challenged the traditional conception of the French monarchy. Upon taking the throne Louis XVI decided to dispense with the political team assembled by his grandfather, Louis XV, and replaced them with ministers such as Turgot, Necker and Calonne. Although serious financial troubles beset the country, the king lent only ambivalent support to their efforts to suppress some of the nation’s many fiscal exemptions. These reforms were doomed to failure, and Louis XVI was eventually obliged to summon a meeting of the Estates General at Versailles, in May 1789. This extraordinary assembly brought together 1200 representatives of the three “orders” which made up the nation: the clergy, the nobility and the third estate. The French Revolution was underway.Louis XVI indulged his interest in the applied sciences and the latest technical and mechanical curiosities in the special cabinets and laboratories he had installed near his private chambers. They included workshops devoted to physics, mechanics, chemistry, woodworking, watchmaking and lock-making, along with a working forge and a room for experiments involving electricity. The king also took a keen interest in maritime exploration and the discovery of new lands. In the 1780s he sponsored the explorer Jean-François de La Pérouse for his circumnavigation of the globe. In 1783 the king hosted the first aeronautical experiments at Versailles: on 14th September, Étienne de Montgolfier floated a balloon filled with hot smoky air and carrying a basket holding a sheep, a rooster and a duck over the palace. On 21 November, Pilâtre de Rozier took off from Versailles and succeeded in remaining airborne for 25 minutes.Louis XIV was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1638. Taking the throne at the age of four following the death of his father, King Louis XIII, the young monarch received a thorough education from his mother Anne of Austria and his godfather Cardinal Mazarin. While his mother ruled as regent and Mazarin busied himself with the young king’s political training, a civil conflict known as the Fronde broke out (1648-1653). Originating as a dispute between the monarchy and the Parlement de Paris, the rebellion subsequently spread to the aristocracy. The child king felt humiliated by the arrogance of the great lords and physically threatened in the capital. He would never forget this experience.Louis XIV married his cousin (on both sides) Maria-Theresa of Austria, the Spanish Infanta, at Saint-Jean-de-Luz in 1660. Their marriage sealed the reconciliation between France and neighbouring Spain. The royal couple had six children. Only the eldest, Louis de France, known as The Grand Dauphin, would survive to adulthood. After the death of the queen in 1683, the king secretly married Mme de Maintenon. She was the last in a series of official mistresses which had included Mlle de La Vallière and Mme de Montespan, with whom he had several legitimated children.At the start of his reign, before turning to more political allegories, Louis XIV chose the sun as his personal emblem. The sun is the symbol of Apollo, god of peace and the arts; it is also the star which gives life to all things, rising and setting with unfailing regularity. Like the god, Louis XIV was a warrior fighting to restore peace; he was also a patron of the arts and the source of all privileges. Though the unstinting regularity of his life and with the public getting-up and going-to-bed ceremonies, he hammered home the symbolic parallels. The Palace of Versailles is replete with representations and allegorical allusions to the sun god combined with royal portraits and emblems.An absolute monarchy. As sovereign by divine right, the king was God’s representative on earth. It is in this respect that his power was “absolute”, which in Latin means literally ‘free of all restraints’: the king was answerable to no one but God. During his coronation, Louis XIV swore to defend the Catholic faith. To honour this pledge and preserve the religious unity of his kingdom, he cracked down on the Jansenists of Port-Royal and ordered the persecution of Protestants. The previous policy of religious tolerance was abandoned with the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Protestants were forced to convert, and over two hundred thousand fled the country. From his base in Versailles, Louis XIV ruled over a centralised, absolutist state which revolved entirely around him. The king lived in the main wing of the palace, on the first floor, in a suite of three apartments reserved for his use. He applied a strict etiquette at court, a set of rules and protocols by which his noble courtiers were obliged to abide. With the help of Colbert, he oversaw the administrative and financial reorganisation of his realm, and also set up manufactures and worked to boost trade. With Louvois he reformed the army and enjoyed a string of military victories. At the beginning of the summer of 1715 Louis XIV complained of a pain in the leg. In mid-August gangrene set in and by 1 September he was dead. He’d been on the throne for 72 of his 77 years. A new exhibition at Versailles looks at the elaborate rituals that followed.The Sun King died as he had lived in public. Despite his illness, he carried on his daily routine until two days before his death, a decision made easier perhaps by the fact that he’d always conducted a good part of the affairs of France from his bedroom. It was no ordinary bedroom, and what went on there wasn’t ordinary either. It is in the exact centre of the palace façade, so the view from his bed would have cut straight down the middle of the magnificent gilted approach to the palace he built, a line which is, not at all coincidentally bien sur, the East–West axis of the sun.

Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were barely in their teens when they married.In the days of the European monarchies, marriage was less a matter of personal inclination than political expediency. Governments interested in forming alliances with other countries would as a matter of course attempt to unite their leaders with the offspring of other royalty. This was the case for Louis-Auguste, third son of the dauphin of France, grandson of King Louis XV.

Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were barely in their teens when they married.In the days of the European monarchies, marriage was less a matter of personal inclination than political expediency. Governments interested in forming alliances with other countries would as a matter of course attempt to unite their leaders with the offspring of other royalty. This was the case for Louis-Auguste, third son of the dauphin of France, grandson of King Louis XV.

On his accession, France was poverty-stricken and burdened with debts, and heavy taxation had resulted in widespread misery among the French people. Immediately after he was crowned, Louis remitted some of the most oppressive taxes and instituted financial and judicial reforms. Calonne was appointed finance minister in 1783. He borrowed money from the court until 1786, when the borrowing limit was reached. The French people, angered by the taxes and the excessive spending of the court, recalled Necker, who, however, could not prevent the bankruptcy of the government. With no other choice, Louis XVI was forced to call a meeting of the Estates-General in Versailles on May 5, 1789.At first the king seemed inclined to work with the Revolution to try to solve the problems. But the influence of the queen and his courtiers was too strong. He was encouraged by them to disregard all promises he had made and sought to flee France in order to obtain aid against the Revolution from Austria. His disregard of his promises to abide by the Constitution led to the storming of the royal palace of the Tuileries on August 10, 1792. The king and his family escaped before the mob arrived and took refuge in the hall of the Legislative Assembly. The Assembly declared that the king was suspended from office and ordered that he and his family should be imprisoned. They then called a new assembly, the Convention, to decide whether France should continue to be a monarchy.The Convention brought Louis XVI to trial on the charge of conspiring with foreign countries for the invasion of France. He was declared guilty and sentenced to death. His execution had important consequences for France, because it increased the prejudice against the Revolution in other countries, which were also monarchies.Joseph was succeeded by his younger brother, Leopold II. Leopold’s reign (1790–92) was a short one, which many believe was quite unfortunate for the Habsburg monarchy because, had he lived, he might have been able to salvage many of Joseph’s reforms. In addition, evidence indicates that he planned to introduce a measure of popular representation into the Habsburg government that might have given the monarchy greater stability as it encountered the challenges of industrialization, nationalism, liberalism, and democracy that became increasingly compelling in the next century.Prior to his accession, Leopold had gained a considerable reputation as an enlightened prince of the Italian state of Tuscany, a land ruled directly by Maria Theresa’s husband and then passed to the second Habsburg son . When he became emperor, Leopold saw as his primary task ending the war with the Turks as quickly as possible. That, he believed, would relieve a great deal of the strain in domestic matters so that he could slowly implement a reform program of his own.By the time of Leopold’s accession, the Turkish war had become somewhat complicated—not in a military sense but in a diplomatic one. In 1788 Prussia and Great Britain had formed a coalition to put pressure on Austria and Russia to conclude the war with little or no compensation. This pressure carried with it the threat of war if the two eastern empires did not comply. In 1789 Joseph had wanted to reach such an agreement, but he could not convince Kaunitz to do so, and Kaunitz still had great influence. Leopold, however, did not hesitate to cast aside the old chancellor’s advice. Two weeks after he reached Vienna, Leopold notified the king of Prussia that he sought an accommodation based on the status quo ante, an accommodation reached in April 1790. The war was effectively over, although peace with the Turks was not concluded until August 1791.Initially Leopold accepted the cancellation of many of Joseph’s reforms and the increasing authority of the secret police under the guidance of Johann Anton, Graf (count) Pergen. But soon the new emperor began to twist this apparent reaction into something far more progressive. In 1790 and 1791 there came to him a number of petitions from the lower classes of society demanding redress of various grievances. Leopold welcomed these petitions and began to cite them as reasons for introducing some changes in the nature of government, including providing greater representation for the lower orders in the provincial diets and placing the police under the rule of the law, a proposal that caused Pergen to resign. In fact, Leopold adopted a proposal of Joseph von Sonnenfels, an official often considered the leading enlightened political theorist in the monarchy, to make the police a service institution rather than an instrument of control. He put them in charge of local health measures and authorized them to settle minor disputes so that people would not have to go to law courts with petty arguments.Apparently, in early 1792 Leopold was beginning to take steps to extend representation in the provincial diets to virtually all classes in society. Clearly he did not intend to establish a constitutional monarchy, but he believed that, by drawing the nonprivileged classes into the government, he could check the resistance of the privileged classes and at the same time create a constituency that would support an improved kind of enlightened absolutism. Whatever he had in mind, however, did not come to pass, for he died prematurely on March 1, 1792.Succeeding Leopold was his much less able but longer-lived eldest son, Francis II (known as Holy Roman Emperor Francis II until 1806 and as Francis I, emperor of Austria, from 1804 to 1835). Francis’s foremost problem was significantly different from those that had faced his father and uncle. The domestic situation was settled again, but foreign matters had become increasingly perilous owing to events in France. The French Revolution had erupted in the summer of 1789, and the initial Austrian policy had been essentially to leave France alone. Indeed, Leopold had at first made some approving remarks about the changes in France, and Kaunitz had noted that at least France would not be a serious force in international affairs for some time. The event that changed these passive responses was the flight to Varennes, when King Louis XVI and his wife, Marie-Antoinette (the youngest daughter of Maria Theresa and therefore sister of Joseph and Leopold and aunt of Francis), fled Paris in June 1791 for the safety of the Austrian Netherlands. They reached the French border town of Varennes, where they were recognized and placed under arrest; later they were returned to Paris.

The reign of Louis XVI, the final Bourbon king of France, was a varied and eventful one, but when we think of him and his queen Marie Antoinette, certain associations inevitably pop into our minds. Perhaps we think of the couple’s ostentatious wealth, as exemplified by their palace at Versailles. Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI had four children. They could not have been born at a more problematic time for the French royal family.The last queen of France has been vilified as the personification of the evils of monarchy. At the same time, Marie Antoinette has also been exalted as a pinnacle of fashion and beauty, with obsessive scholarship on her choices in wardrobe and jewelry and endless speculation about her extramarital love life.

The reign of Louis XVI, the final Bourbon king of France, was a varied and eventful one, but when we think of him and his queen Marie Antoinette, certain associations inevitably pop into our minds. Perhaps we think of the couple’s ostentatious wealth, as exemplified by their palace at Versailles. Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI had four children. They could not have been born at a more problematic time for the French royal family.The last queen of France has been vilified as the personification of the evils of monarchy. At the same time, Marie Antoinette has also been exalted as a pinnacle of fashion and beauty, with obsessive scholarship on her choices in wardrobe and jewelry and endless speculation about her extramarital love life.

Maria Antonia was born on 2 November 1755 at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria. She was the youngest daughter of Empress Maria Theresa, ruler of the Habsburg Empire, and her husband Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor.Her godparents were Joseph I and Mariana Victoria, King and Queen of Portugal; Archduke Joseph and Archduchess Maria Anna acted as proxies for their newborn sister. Shortly after her birth she was placed under the care of the governess of the imperial children, Countess von Brandeis.Maria Antonia was raised together with her three-year older sister Maria Carolina, with whom she had a lifelong close relationship.She had a difficult relationship with her mother, but both the empress and her daughter loved each other.Archduchess Maria Antonia (watercolor by Jean-Étienne Liotard, 1762) .Maria Antonia spent her formative years between the Hofburg Palace and Schönbrunn, the imperial summer residence in Vienna, where on 13 October 1762, when she was seven, she met Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, two months her junior and a child prodigy Despite the private tutoring she received, the results of her schooling were less than satisfactory.At the age of ten she could not write correctly in German or in any language commonly used at court, such as French and Italian, and conversations with her were stilted.Following the Seven Years' War and the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, Empress Maria Theresa decided to end hostilities with her longtime enemy, King Louis XV of France. After 1789 Louis XVI’s incapacity to rule, his irresolution, and his surrender to reactionary influences at court were partially responsible for the failure to establish in France the forms of a limited constitutional monarchy. He allowed himself to be persuaded that royal dignity required him to avoid communication with the deputies assembled at Versailles, and he made no attempt to lay out a program that might have attracted their support. At critical moments, he was distracted by the illness and death of his eldest son, the dauphin (June 4, 1789).By this time the fundamental weakness of the king’s character had become evident. Lethargic in temperament, lacking political insight, and therefore incapable of appreciating the need to compromise, Louis continued to divert himself by hunting and with his personal hobbies of making locks and doing masonry. His dismissal of Necker in early July 1789 set off popular demonstrations culminating in the storming of the Bastille, which forced the king to accept the authority of the newly proclaimed National Assembly. Despite his reluctance, he had to endorse its "destruction" of the feudal regime and its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August. The king privately continued to believe that the Revolution would burn itself out. Publicly, however, he appeared ready to accept his new role as constitutional monarch, and gestures such as his visit to Paris after the storming of the Bastille led to an upsurge in his popularity; in early August 1789 the National Assembly proclaimed him the “restorer of French liberty.Their common desire to destroy the ambitions of Prussia and Great Britain and to secure a definitive peace between their respective countries led them to seal their alliance with a marriage: on 7 February 1770, Louis XV formally requested the hand of Maria Antonia for his eldest surviving grandson and heir, Louis-Auguste, Duke of Berry and Dauphin of FranceAt first, Marie-Antoinette was beloved by the people of France as the embodiment of youth, beauty and promise.She gave generously to those in need. But, at court, factions were forming.Tongues were wagging. Was her husband, Louis XVI impotent? Marie-Antoinette must be getting satisfaction elsewhere from the king’s handsome younger brother from her good friend Princess Lamballe, newly appointed Mistress of the Wardrobe, and later Madame Polignac, governess to her children (when she did finally produce them).Irritated by the crushing court etiquette, Antoinette dismissed those whose positions had been a closely guarded privilege, and instead selected friends who amused her. As a result, enemies were piling up.Louis, a bit of a slouch, wasn’t all that popular either. His cousin, Philippe d’Orléans, had his eye on the throne. So did Louis’ younger brothers. And they were all happy to criticize him, the indecisive fool, and his wife, the spendthrift shrew. They fueled demonizing broadsheets in Paris and printed some of their own.These damning newspapers and pamphlets appeared with increasing frequency and virulence as the revolution was about to explode! By 1785, the once-beloved Antoinette was known as the “Autrichienne” (the Austrian bitch) after she pushed her influence on Louis to help her brother, the Archduke in a political fracas in Poland. Louis didn’t come to Austria’s aid, but the fear was there. Antoinette’s ulterior allegiance must be to her native country.State bankruptcy was looming in France. The broadsheets printed stories of Antoinette’s huge expenses, inciting the new epithet “Mrs. Deficit”. Her expenditures were a concern and definitely over-the-top. The same could be said of Louis XIV’s mistress, Madame de Montespan and Louis XV’s mistress, Madame du Barry. However, nobody printed their extravagances.Then came the fluke hail storm and crop failure of 1788. Already detested, mistrusted and dragged through the media mud, another smear came into print. The heartless queen was reported to have said, if there was no bread to be had, then the people should eat brioche . She never said it, but people believed it. Her detractors took advantage of the suffering to fabricate another smear about her in the press. And it’s still taught in history books today – 2 centuries later – a testament to the power of the press in its burgeoning days. When queen of France Marie Antoinette was indicted in August 1793, months after the execution of her husband Louis XVI during the French Revolution, she asked that she would not “suffer long”. However, she went on to spend two and a half months living in squalor before her trial and eventual execution for treason. Here, Will Bashor shares the final events of Marie Antoinette's life, including an escape attempt which would become known as the Carnation Affair.The tragic tale of Marie Antoinette's death during the French Revolution is the stuff of legend. But while the story of Marie Antoinette ends with her beheading in 1793, the tragedy of her family continued to unfold long after her death.Marie Antoinette and her husband, the Dauphin, were married for seven years before consummating their marriage much to the chagrin of Marie's family, particularly her critical mother, the Empress Maria Teresa of the Holy Roman Empire. Marie's place in the royal household of France and Franco-Austrian relations absolutely depended on her producing a male heir, even before her husband became the King of France in 1774. Despite the rocky start, Marie and Louis XVI would have four children only one of whom lived to adulthood.Marie Antoinette's first child was a girl, named Marie Thérèse after Marie's mother. When she was born on December 9, 1778, Marie Antoinette suffered a convulsive fit and collapsed, not surprising after 12 hours of labor in her stuffy room and the possibly dangerous incompetence of her doctor. The Queen wasn't informed the sex of the child until hours later. But when she woke, she reportedly said, "Poor little girl, you are not what was desired, but you are no less dear to me on that account. A son would have been property of the state. You shall be mine." There certainly would have been witnesses to the episode: Court custom at the time dictated that queens gave birth in full view of their courtiers.Louis Joseph, the King's male heir and the next Dauphin of France, was born three years later, followed by Louis Charles in March of 1785 and Sophie in July of 1786. But Sophie, who was born premature, died just a month shy of her first birthday, and Louis Joseph, who'd been a delicate child most of his life, died two years later, at the age of 7, likely from tuberculosis.

Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France, spent the final two months of her life in this prison, before her execution on October 16th, 1793.Her figure, which can only be seen from behind, is shown sitting in a cell at a small wooden desk, guarded by a member of the National Guard . Contrary to its appearance, this scene is not set in the cell in which the queen was actually imprisoned, but is only meant to be an accurate reconstruction.The cell in which Marie-Antoinette was imprisoned still exists, but not as a cell.

Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France, spent the final two months of her life in this prison, before her execution on October 16th, 1793.Her figure, which can only be seen from behind, is shown sitting in a cell at a small wooden desk, guarded by a member of the National Guard . Contrary to its appearance, this scene is not set in the cell in which the queen was actually imprisoned, but is only meant to be an accurate reconstruction.The cell in which Marie-Antoinette was imprisoned still exists, but not as a cell.

During the Revolution, after the government had placed the royal family under house arrest in the Tuileries Palace in October 1789, several events linked to Marie Antoinette, in particular the June 1791 attempted flight to Varennes and her role in the War of the First Coalition, had disastrous effects on French popular opinion.Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793; Marie followed 10 months later, on October 16. On June 8, 1795, their son, the Dauphin and the boy royalists had named Louis XVII, died at the age of 10, most likely of tuberculosis exacerbated by his brutal prison conditions.

During the Revolution, after the government had placed the royal family under house arrest in the Tuileries Palace in October 1789, several events linked to Marie Antoinette, in particular the June 1791 attempted flight to Varennes and her role in the War of the First Coalition, had disastrous effects on French popular opinion.Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793; Marie followed 10 months later, on October 16. On June 8, 1795, their son, the Dauphin and the boy royalists had named Louis XVII, died at the age of 10, most likely of tuberculosis exacerbated by his brutal prison conditions.