EMPRESS CATHERINE THE II OF RUSSIA (CATHERINE THE GREAT)( 1729 -1796).THIS REMARKABLE WOMAN WAS NEITHER RUSSIAN NOR ORIGINALLY NAMED CATHERINE.SHE WAS A GERMAN PRINCES WHO WAS SENT TO RUSSIA IN A DIPLOMATIC PRUSSIAN INTRIGUE. BORN SOPHIE FRIEDERIKE AUGUSTE VON ANHALT - ZERBST,GERMANY.

Catherine, who ruled Russia for three decades until her death in 1796, viewed herself a patron of the arts and liberty, and a "philosopher on the throne", but has been criticised for the little she did for the millions of peasants in her empire.Voltaire supported her military endeavours, including her war against the Turks. Mr Bompard said that after Louis XVI's wedding to Marie Antoinette, the monarch, soon to be deposed by the French revolution, celebrated by setting off hundreds of fireworks which apparently killed many bystanders. "He wrote that more people were probably killed by the fireworks than by Catherine's war against the Turks.

Catherine, who ruled Russia for three decades until her death in 1796, viewed herself a patron of the arts and liberty, and a "philosopher on the throne", but has been criticised for the little she did for the millions of peasants in her empire.Voltaire supported her military endeavours, including her war against the Turks. Mr Bompard said that after Louis XVI's wedding to Marie Antoinette, the monarch, soon to be deposed by the French revolution, celebrated by setting off hundreds of fireworks which apparently killed many bystanders. "He wrote that more people were probably killed by the fireworks than by Catherine's war against the Turks.

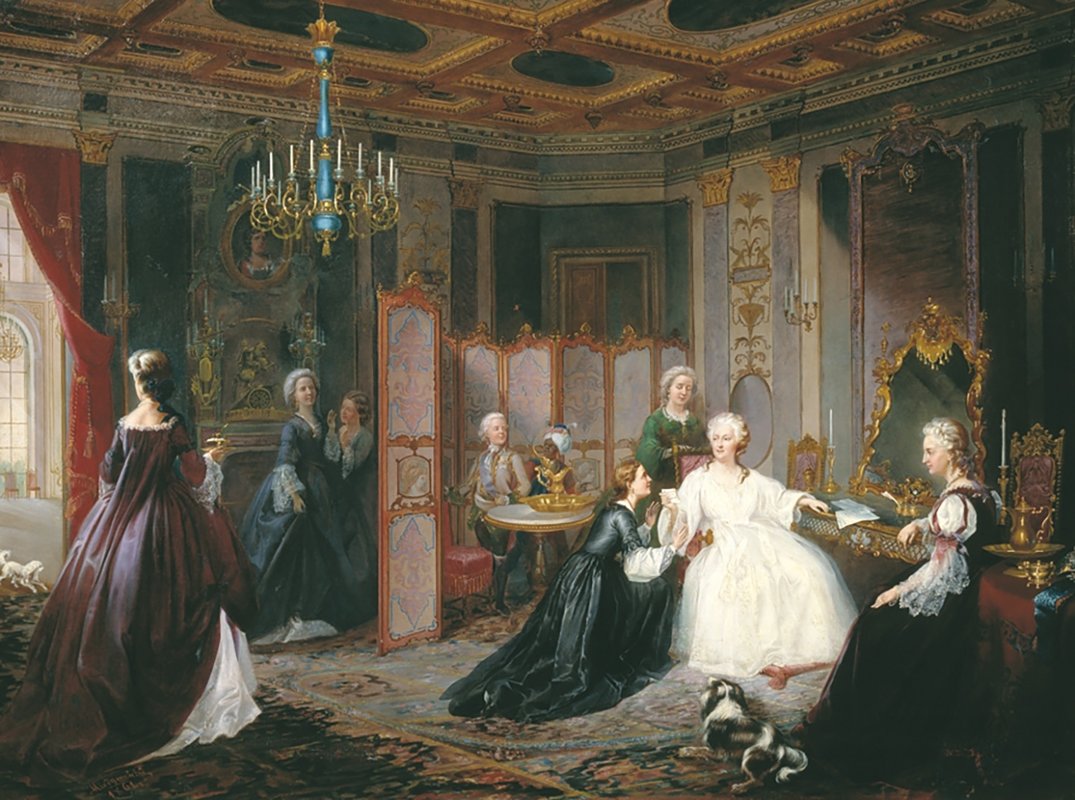

Catherine II of Russia (also known as Catherine the Great) was born in Stettin, Pomerania, Prussia as Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg. She was a German princess who was sent to Russia in a diplomatic Prussian intrigue and grew more popular than the man she married, the Grand Duke Peter - later Peter III. After his death she became empress, extending the Russian empire south and westwards. She considered herself a philosopher, and the arts flourished. . She corresponded with the great minds of her day, including Voltaire, who called her "the Star of the North".She was raised in an environment of German culture and traditions. Although born a princess, her family had little money and an arrangement was made for her to marry Peter III who stood in the line of succession to the Russian throne. She arrived in Russia in 1744 and married Peter in 1745. Catherine became Empress of Russia in July 1762 following a coup d'état and the assassination of her husband, Peter III, who had recently become Emperor following the death of his mother, the Empress Elizabeth. Catherine's accession to power came at the end of the Seven Years' War, a religious and political struggle that left much of Western Europe in dire economic and social conditions.Catherine had aspirations for the Russian throne at an early age. The study of her family’s connections to royalty gave her hope that she could also be a part of the nobility. Catherine inferred that “this idea of a crown began running in her head like a tune, and has been running a lot in it ever since.” Achieving political success however was difficult because she had few allies in the beginning. She later learned that she could overcome this by practicing neutrality. “I tried to be as charming as possible to everyone and studied every opportunity to win the affection of those whom I suspected of being in the slightest degree ill-disposed towards me it pleased me when I realized that I was daily winning the affection of the public.” In addition to learning politics actively, the future Empress became an avid reader of Plutarch, Tacitus, Machiavelli, Montesquieu and most importantly, Voltaire. “She had a profound understanding of the nature and important of public opinion, and of the need to mold it” . Her fascination with enlightenment principles led her to be a proponent for civil rights and the position that government had a duty to provide security and welfare to its citizens.Like Sophie, Peter was German-born, but this was almost all that the new couple had in common. Peter, who was at the very least eccentric, loathed the country into which he had been imported as child heir, and remained a staunch supporter of all thingsPrussian, especially the Prussian military, which did nothing to ingratiate him to his new subjects. Sophie, on the other hand, came to Russia committed to doing whatever had to be done and to believing whatever was required to be believed in order to qualify for the crown. She learned the Russian language, converted to Orthodoxy, whereby she received the name Catherine, and with charm and determination carefully cultivated long-term relationships with the powerful and the well-connected. Thus, after the death of Elizabeth in 1762, a swift and bloodless palace coup was all it took to remove the hapless Peter from the throne upon which he had sat a mere six months and to replace him with the charismatic Catherine. And so, this German princess, with no Russian blood in her veins and no legal right to rule, became the sole occupant of the Empire's throne from which she governed for the next thirty-four years - longer than any of the country's other women sovereigns.On August 21, 1745, when Peter was just seventeen, he married a young, intelligent princess from Anhalt-Zerbst, in Germany, named Sophie Frederike Auguste, who took the name Yekaterina Alekseyevna, or, as we better know her in history, Catherine.It was a terrible match. Catherine was a girl of prodigious intellect, savvy at court, and she did her best to Russianize herself, get her courtiers to warm to her and to make allies her new home. Peter, on the other hand, was an epic man-child. He spent every night in bed with her playing with the toy soldiers he was so obsessed with. Sometimes, he would force his new wife to dress up as a soldier so he could pretend to be a general and put her through intense, rigorous military drills. When he grew bored of that, he’d beat his hunting dogs.The story goes that, one time, after he’d spent hours meticulously setting up his toy soldiers in pretty rows all throughout his bedroom, a rat came out of the woodwork and chewed the head off of one of Peter’s toys. The young Czar was so incensed that he caught the rat and held a proper military court martial for it. He proclaimed the rat guilty of treason and hung it on a tiny gallows he’d constructed just for the occasion. His wife, Catherine wrote about this event and many others in her memoirs, depicting him as an idiot, a drunkard, prone to brutal practical jokes and interested only in playing with his toy soldiers.Now, he might have ruled for many years (insane rulers often did), except for one thing: Peter was obsessed with Germany and Prussia, and he hated Russia, and Russia hated Peter. The moment Peter III became Czar of Russia, he reversed his aunt’s foreign policy against Prussia, withdrew Russia from the war with Frederick the Great (even though Frederick was losing!), and, as if that wasn’t enough, he struck an alliance with Prussia and planned to start a war with Denmark! On top of all that, he alienated the Russian Orthodox church when he attempted to force it to adopt Lutheran religious practices, and thought it would be an excellent idea to threaten to disband his own personal guard.

On August 21, 1745, when Peter was just seventeen, he married a young, intelligent princess from Anhalt-Zerbst, in Germany, named Sophie Frederike Auguste, who took the name Yekaterina Alekseyevna, or, as we better know her in history, Catherine.In all of six months, Peter III was without friends at court and without a loyal personal guard. He’d managed to make all of Russia angry. Around the year of 1762, when he was just 34, his wife, Catherine, suspected that he meant to divorce her. Well, Catherine was intelligent and completely capable of ruling by herself, and she had many supporters at court. She was not about to lose the Russian throne. So, she conspired with her lover and other members of Peter III’s own guard to overthrow him.

On August 21, 1745, when Peter was just seventeen, he married a young, intelligent princess from Anhalt-Zerbst, in Germany, named Sophie Frederike Auguste, who took the name Yekaterina Alekseyevna, or, as we better know her in history, Catherine.In all of six months, Peter III was without friends at court and without a loyal personal guard. He’d managed to make all of Russia angry. Around the year of 1762, when he was just 34, his wife, Catherine, suspected that he meant to divorce her. Well, Catherine was intelligent and completely capable of ruling by herself, and she had many supporters at court. She was not about to lose the Russian throne. So, she conspired with her lover and other members of Peter III’s own guard to overthrow him.

Czar Peter III of Russia was born on February 21, 1728, in Kiel, Germany. Karl Peter Ulrich was the only son of Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp and of Anne Petrovna, eldest surviving daughter of Peter the Great. Until his adoption by Elizabeth Petrovna, he lived at the court of Holstein.He was son of Anna, one of Peter the Great’s daughters, and Charles Frederick, duke of Germany, which made him technically German. How on earth did he become Czar of Russia, then? Well, he wasn’t supposed to be originally. In fact, he was the grandson of Charles XII of Sweden, on his father’s side, which meant that once his parents died when Peter was young, he was placed into the care of tutors and officials at the German court. Their job was to groom him for the Swedish throne.Young Peter had a very unhappy childhood. His tutor was a cruel, sadistic man, and Peter was a very poor student. He had a lot of interest in the arts, but he failed in nearly every academic subject. Consequently, he was beaten, starved, and generally mistreated during the formative years of his life. It was a treatment that would later forge him into a strange breed of manchild-psychopath.When Peter III was just fourteen, his closest relative, his aunt Elizabeth on his mother’s side, became Empress of Russia. She whisked young Peter away from everything he knew, renamed Pyotr Fyodorovich, inducted into the Russian Orthodox faith, and proclaimed him heir to the Russian throne. The trouble was, Peter hated living in Russia, and the Russian people hated Peter.In December 1741, Karl Peter Ulrich was adopted by his aunt, Elizabeth Petrovna, as soon as she was safely established as Empress of Russia.On November 18 1742, Karl Peter Ulrich was received into the Orthodox Church, exchanging his original name for that of Peter Fedorovich.On August 21 1745, by the command of his aunt, Peter married Princess Sophia Augusta Frederica of Anhalt-Zerbst, who exchanged her name for that of Catherine Aleksyeevna. Their tastes were divergent and their tempers incompatible.On January 5 1762, Peter succeeded his aunt Elizabeth Petrovna as Peter III. His immediately proclaimed an amnesty for the statesmen arrested or exiled by Elizabeth after her accession. His foreign policy was the absolute reversal of the policy of his predecessor. At the end of February, he made pacific overtures to the almost vanquished King Frederick II of Prussia, whom he habitually alluded to as "the king my master." On May 5, Peter's enthusiastic worship of Frederick II resulted in a peace. On June 19, he even entered into an offensive and defensive alliance with Prussia whereby Peter restored to Prussia all the territory won from her by Russia during the last five years. Peter III then sent a series of menacing letters to the Court of Vienna, threatening to attack Austria unless it complied with all the demands of the King of Prussia. On July 6, Peter III ordered the Russian army to invade Denmark by way of Mecklenburg. This conflict was due to the refusal by Denmark of the terms to be submitted by Russia to a peace conference to meet at Berlin for the purpose of adjusting the differences between the two powers.Meanwhile, Peter III paid off all the debts that his wife Catherine had contracted as soon as he acceded to the throne. On her birthday, in April, he made her a present of large domains though he had already readjusted her establishment on a truly imperial scale. Meanwhile Peter III had a liaison with Countess Elizabeth Vorontsova who was invited to the Winter Palace. Catherine accepted it as a matter of course. She had her own love affair with the young guardsman, Gregory Orlov. However, Catherine soon resolved to snatch the reins of government from the hands of Peter III.On July 9 1762, Catherine led a coup d'état against Peter III. Immediately after his surrender, Peter was removed to Ropshinskyi Castle. Catherine then sent messengers to stop the advance of the Russian army against Denmark. When these messengers finally reached their destination, the opposing forces were almost within touch of each other.Peter was kept prisoner at Ropshinskyi Castle from July 9 to July 18. At first Catherine and her counselors could not make up their minds what to do with "the former emperor". They initially considered imprisoning him for life in the Fortress of Schlüsselburg or repatriating him to Holstein. However, these alternatives were both considered as too dangerous. The Orlovs had even stronger motives than Catherine herself for suppressing the ex-emperor. With the elimination of Peter, Gregory Orlov could aspire to marry Catherine, thus becoming emperor. Finally, on the afternoon of July 18, Peter III, along with his consort's connivance, was murdered at Ropshinskyi Castle by Alexius Orlov, Theodore Baryatinski and several others.Catherine and Peter tolerated each other’s affairs with indifference. Her estrangement to Peter became the catalyst for the affair with lover Sergius Saltykov. In 1754, after almost nine years without producing a child with Peter, she gave birth to the heir, Paul. “Later, an important point of controversy arose over the identity of Paul’s biological father Peter or Sergius endangering her son’s claim to the throne” Catherine’s personal memoirs suggest that Peter, who is suspected of being infertile, is not the father to Paul. Paul would later attempt to burn all records of these allegations to secure his place as heir. Elizabeth took Paul away the moment he was born from Catherine. She did not see much of her son in the beginning and throughout his life, straining their relationship indefinitely.His foolish bias towards Prussia created far too many enemies amongst the Russian court and military. In time, the nobility realized that Catherine was the only legitimate alternative to Peter. The former Empress Elizabeth had already died and she eventually favored Catherine over Peter. Catherine used the help of guards and other influential figures of the Russian court to conspire against her husband. The Orlov brothers were the key allies in her aid. The coup had to be defended from retaliation from Peter, Ivan VI, and her son Paul. Peter was killed by the officers who guarded his imprisonment. Two years later, Ivan VI (great-grandson of Peter the Great’s half-brother Ivan V who had been languishing in a monastery since Elizabeth’s coup) died. “He was found lying on the floor in a pool of blood” . Paul’s claim to the throne was rejected by Catherine continuously. It is clear that Empress Catherine learned a great deal from her time as Grand Duchess. Her charm and neutrality allowed her to gain favor with the men who could help her defeat Peter. The murder of Ivan VI and suppression of her son Paul has clear Machiavellian ruthlessness in its essence. She balanced cleverness with brutality.Catherine writes :“we rulers were created for our people for God’s forbid that after this legislation is finished any nation on earth should be more just and, consequently, more flourishing.” This led her to propose legislation that would benefit a greater segment of the population. Notably, her reforms excluded the serfs in Russia. To her, a privileged gentry meant a closer supervision of the popular mood and tighter control over incipient unrest.

On July 9, 1762, Catherine, with the approval of the Russian guard, the Russian Orthodox Church, and the entire senate, became Catherine II, Empress of Russia. She forced Peter to formally abdicate, and he was arrested and taken into custody. Just nine days later, on July 18th, 1762, he was assassinated, probably at Catherine’s own command.

On July 9, 1762, Catherine, with the approval of the Russian guard, the Russian Orthodox Church, and the entire senate, became Catherine II, Empress of Russia. She forced Peter to formally abdicate, and he was arrested and taken into custody. Just nine days later, on July 18th, 1762, he was assassinated, probably at Catherine’s own command.

For decades, Russia had attempted to productively colonize its empire to the south after winning territory from the Ottoman Empire. The government felt that the area along the lower Volga River was unstable and bands of roving bandits made settlement impossible. Catherine and her government wanted to solidify this region as Russian territory and she needed free settlers who would turn the land into productive farms and serve as a model for native people living in the area.An attempt was made to lure colonists to the region in 1731, but fears about the lack of military protection resulted in almost no interest. In 1732, Empress Anna Ivanova resettled a group of over 1,000 Don Cossack families along the lower Volga under the pretext of protecting and stabilizing the frontier. The Cossacks reportedly made poor colonists and often took part in looting the trade routes in the region.Attempts in the 1740's to attract Russian subjects to the lower Volga was problematic as serfdom prevented the free movement of the general population. The serfs were bound to the landowners who had no interest in releasing their workers or weakening the class system. Landowners were reluctant to create new farms in the troubled region. As a result, the Russian government began to look beyond its borders for colonists.The question of inviting foreigners was resolved by Empress Elisabeth. During her reign the basic legal and economic questions about colonization were answered and a government resolution encouraging settlement in Russia was sent to the Russian ambassadors living abroad on May 2, 1759. Active recruitment of colonists would have to wait until the conclusion of the Seven Year's War which ended in 1763. Sadly, Empress Elisabeth died on January 5, 1762 and would not see her colonization plans carried out.Shortly after becoming the next Empress of Russia, Catherine II approved a new colonization policy designed to benefit her empire on October 14, 1762. Catherine’s first Manifesto, issued on December 4, 1762, was printed in Russian, German, French, English, Polish, Czech, and Arabic. This Manifesto was largely symbolic given that the Russian government had not yet established an administrative structure to plan and manage such a large colonization program.Catherine’s second Manifesto was issued on July 22, 1763, at the end of the Seven Years' War. This Manifesto was perfectly timed to appeal to the war and tax weary European populace. Copies of the Manifesto were printed in newspapers and on leaflets that were distributed throughout Europe, but with a focus in the German speaking lands where much of the war had been fought. These lands had no national government and were comprised of a large number of small principalities, counties, duchies and city states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Some of these territories, such as the County of Isenburg, did not have legal restrictions preventing their subjects from traveling or migrating to new lands.The second Manifesto was enhanced to be make the offer more specific and attractive. Among the promises made to the colonists was exemption from military service, freedom of religion, a 30 year exemption from taxes, land provided at no cost and travel expenses paid by the Russian government. At the time, and even by today's standards, this was a very enlightened and generous offer to prospective immigrants.The Manifesto of 1763 had great appeal to many who were seeking a better life. Over 30,000 people began their migration to Russia between 1763 and 1766.An Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers was established under the leadership of Catherine's trusted friend, Count Grigory Orlov, to plan and administer the colonization program. The Guardianship reported directly to Catherine and Count Orlov reported to her on the conditions in Norka in 1769.The Manifesto was soon followed by many supplementary stipulations. On February 19, 1764 Catherine approved the "agrarian law" for the colonists, which was developed by Grigory Orlov. The law defined the basic conditions of the settlement and the organization of the foreign settlers.Several provisions of the 1763 Manifesto were never truly fulfilled, such as the promise that colonists were free to settle anywhere in the Russian Empire, including towns and cities, and to practice their trade. After arrival in Russia, nearly all of the colonists were directed to settle in the Volga region near Saratov where they would primarily work as farmers and practice their trade as time allowed.After more than 100 years of settlement in Russia, all of the remaining provisions of the 1763 Manifesto were revoked between 1871 and 1874. The loss of the privileges promised by Catherine sparked another large scale migration of these ethnic Germans, this time to the Americas.At the time of Catherine's accession, Russia was still regarded as a distant provincial wilderness by many Europeans. Catherine, who understood the power of image and symbol, sought to change this negative view by creating a powerful, modern, wealthy country ruled over by a sophisticated, enlightened autocrat (herself). She therefore purposefully became a patron of literature, science, the arts, and education - not only because she believed these fields to be important in and of themselves, but because she understood that success here would contribute to Russia's reputation as a center of civilization. She founded elementary schools, academies, libraries and other institutions of learning across the empire. Russian scholars and artists were sent abroad to learn from Western examples, and foreign scientists, architects, and artists were attracted to Petersburg in order to enrich the city's appearance and cultural life. The Empress herself laid the foundation stone for the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in 1765: since its completion, this magnificent early neoclassical edifice crowned by a statue of Minerva has been the alma mater of a plethora of Russian painters, sculptors and architects.Catherine II the Great’s coup and subsequent rule impresses historians when considering the circumstances. She began her career in court as a foreigner to the political game. Her ambition however led her to take the throne away from her imprudent husband. She survived Paul’s, Ivan VI, and Peter’s attempts at gaining power. With her charm and wit, she gained the approval of the men closest to her court. With all her praise intact one must note that “by her stratification of classes in Russia, she perhaps did more to prepare the coming of the 1917 revolution than any other single Russian monarch.” Her legislation, although progressive, festered into future complications. In hindsight, historians propose that her reign has a great deal to do with the arrival of the Bolshevik Revolution a century later. Regardless of perspective, Catherine will be remembered for her leadership in a time of unprecedented Russian political growth.

Catherine II granted Cossacks lands.The Zaporizhian Sich grew rapidly in the 15th century from serfs fleeing the more controlled parts of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It became established as a well-respected political entity with a parliamentary system of government. During the course of the 16th, 17th and well into the 18th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks became a strong political and military force that challenged the authority of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Tsardom of Russia, and the Crimean Khanate.The Cossacks served a valuable role of conquering the Caucasian tribes and in return enjoyed considerable freedom granted by the Tsars.

Catherine II granted Cossacks lands.The Zaporizhian Sich grew rapidly in the 15th century from serfs fleeing the more controlled parts of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It became established as a well-respected political entity with a parliamentary system of government. During the course of the 16th, 17th and well into the 18th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks became a strong political and military force that challenged the authority of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Tsardom of Russia, and the Crimean Khanate.The Cossacks served a valuable role of conquering the Caucasian tribes and in return enjoyed considerable freedom granted by the Tsars.

Catherine maintained voluminous correspondence with the French Enlightenment philosophers Voltaire and Diderot. When the former, who called her the "Star of the North", died, she wept, and then bought his book collection. And when the latter fell upon hard times, the Empress - who he said possessed the charm of Cleopatra and the soul of Caesar - purchased his personal library, generously leaving it in his possession until his death and paying him a salary as a librarian. Such renowned acquaintances increased Catherine's prestige and such important acquisitions expanded the Imperial library from a few hundred volumes to 38,000. Meanwhile Catherine further stunned Europe by spending vast sums of money purchasing masterpieces of art. Her outstanding collection, containing works by Raphael, Rubens, Rembrandt, and many others, was the largest in Europe and formed the basis for one of the world's most magnificent museums: the Hermitage. Catherine likewise maintained a court worthy of such magnificence - more than one of every ten rubles in the state budget was spent on court expenses. Not that the Empress did not enjoy an extravagant ball or an impressive diplomatic reception, but she also understood the symbolic significance that such grandeur conveyed to awed Western beholders.Catherine might well have achieved more had the infrastructure in Russia been better equipped for major societal transformations. In reality, she was attempting to transplant progressive Western ideas from the Age of Enlightenment into the vast expanses of Russia at a time when serfs comprised the majority of the population. In addition, the Russian nobility was generally conservative and wary of reforms, especially when it came to issues like freeing the serfs. Despite such impediments, Catherine nonetheless left the country stronger, wealthier and more beautiful than she had received it. She continued the westernization begun under Peter the Great, significantly expanded the empire's territory, and imported a wealth of literature and art. The French ambassador to Russia in the 1780s wrote: "The court of Catherine was the meeting place of all European monarchs and celebrities of her age. Before her reign, Petersburg, built in the realm of cold and ice, went almost unnoticed and seemed to be somewhere in Asia. During her reign Russia became a European power. St. Petersburg occupied an important place among the capitals of the educated world and the Russian throne was raised as high as the most powerful and significant thrones."If there ever was a Europhilic ruler that embodied the simultaneous retention of and privileging of autocratic rule through numerous, simulative exchanges between Western Europe and “European Russia,” and who perpetually employed, was fascinated with, deflected, and then downright rejected certain European Enlightenment ideas on principle, such a ruler was no one other than Catherine the Great, Empress and Autocrat of All the Russias. Catherine, though German-born, after becoming betrothed to Peter the III, converted to the Russian Orthodox Church and learned Russian. Before her reign and during her reign, Catherine was an inveterate admirer of Western culture. She had traveled all over Europe as a young woman, and had devoured French Literature and philosophy in various passionate spurts and critical distances. Catherine, a ruler many traditional scholars have dubbed an “enlightened despot,” if anything, serves as a prime example of collusive and prevailing ambiguities inherent within Eastern European/Russian autocracies during the 18th and 19th centuries.Whereas the Enlightenment was in full bloom during Catherine’s rule and the bubbling specters of Romanticism were always already inherent as a direct assault on the notions of “universal Reason,” such specters were not only within Western Europe, but also within Russia, which never “fully” embraced Enlightenment ideas, but certainly entertained them.Catherine here makes the distinction between theory and action abundantly clear. That is, Catherine is certainly charmed by Diderot’s “brilliant mind.” However, she insists on emphasizing the difference between Enlightenment thought and her own position that “works on human skin, which is far more sensitive and touchy.” Such ambiguous statements, of course, those which work “on human skin” evoke a distancing, an essentialist position, a ‘we are not you’ take on Western ideas. Yet, Catherine, in practice, through her later codification of laws, her famous “Nakaz” claims something quite different.Catherine’s predication of Voltaire as “so good a Russian” indicates something inherently intimate. They only communicated through letters, and as it was pointed out above, it was Diderot who went to Russia to visit her court, not Voltaire. Strangelyenough, however, Voltaire in another letter emphasizes that his dying wish was to be buried in Russia, writing “why should I not have the pleasure of being buried in some corner of Petersburg, where I could see you pass to and fro under your arches of triumph, crowned with laurel and olive?” Voltaire is either obsessed with Catherine, obsessed with dying in Russia, or obsessed with the East in general. Perhaps, all of these are true for the Voltaire-Catherine-West-East exchange during the period of the so-called Enlightenment are indicative of “orientalism” in both political spheres, Eastern and Western Europe: the frugal application of conceptual framework which Russia, in this case, under Catherine the Great, refused to accept and the West’s unbridled fascination with the East.7 Such undertones of fascination bring to mind themes of power dynamics which resonate in the Prussian novel Venus in Furs by Sacher-Masoch, which not only reeks with direct references to Catherine the Great but also underscores the sexual/intellectual phantasms between Western “Enlightenment elites” and “Slavic monarchs” who, both operating upon an “orientalist” axis, stop nothing short of redefining “Enlightened Despotism” as nothing short of “orientalist” perversion.The “human skin” factor, however, reveals something else about Catherine the Great: she quite literally flirted both politically and erotically with Western Europe. When Diderot returned to France, Voltaire grew jealous, writing to the Empress:Madame, I am positively in disgrace at your court. Your Imperial Majesty has jilted me for Diderot, of for Grimm, or for some other favorite. You have had no consideration for my advanced age. All is well and good if your Majesty were a French coquette; but how can a victorious, lawgiving Empress be so inconstant I am trying to find crimes I have committed that would justify your indifference. I see that there is indeed no passion which does not end.Voltaire once noted the usefulness of keeping a few crowned heads up one’s sleeve; for her part, Catherine of Russia found profit in having at her disposal an assortment of philosophes.Within weeks of her accession in 1762, she took steps to win over the luminaries of France with an irresistible combination of flattery and spectacular generosity.For all their love of reason, the philosophes succumbed quickly to her blandishments, thinking so much the more of the Empress of Russia - so unlike the French authorities - who acknowledged their merit with such handsome marks of esteem.'If I Were Younger I Would Make Myself Russian': Voltaire's Encounter With the Czars.Voltaire spoke for the 18th century's amazement at the phenomenon of Russia, its revolutions and transformations, unforeseeable and unimaginable to those who watched from far away.

A Forgotten Love Triangle: Voltaire, Diderot, and Catherine the Great.Voltaire apparently was either an “orientalist” who Catherine entertained from time to time in his correspondences with her, who took offence that he was “jilted” for Diderot, or Catherine and Voltaire were both “orientalists” who quite frankly used Western European rhetoric to intellectually seduce one another. Catherine responds to Voltaire:Monsieur, and let us be reconciled; for in any case there is no cause for quarrel between us you are so good a Russian that you could not be the enemy of Catherine.

A Forgotten Love Triangle: Voltaire, Diderot, and Catherine the Great.Voltaire apparently was either an “orientalist” who Catherine entertained from time to time in his correspondences with her, who took offence that he was “jilted” for Diderot, or Catherine and Voltaire were both “orientalists” who quite frankly used Western European rhetoric to intellectually seduce one another. Catherine responds to Voltaire:Monsieur, and let us be reconciled; for in any case there is no cause for quarrel between us you are so good a Russian that you could not be the enemy of Catherine.

How Voltaire praised the 'enlightened despot' Catherine the Great.In Voltaire's bedroom there was a portrait of Catherine in front of his bed."Satirist's heartfelt letters to the woman he admired are bought for Russia.They are the heartfelt correspondence from the great acerbic wit of the European Enlightenment to the last Russian empress, in which he praises her authoritarian style and mocks the extravagances of her French counterparts.Our own century has witnessed revolutions in Russia no less astonishing and unpredictable, right up to the most recent years; tremendous events have left every interested observer, even the visionaries, reeling from the pace at which history has outstripped our imaginations. Voltaire was not altogether unintimidated by the unforeseen success of Russia, of an empire "more vast than all the rest of Europe, than the Roman empire ever was, or that which Alexander conquered from Darius." At the same time, his notion of Russia's volatility allowed him to imagine its success as something precarious, even reversible; he wondered hypothetically if "the most vast empire on earth might relapse into the chaos from which it had only barely emerged." In his trepidation, as in his amazement, Voltaire speaks directly to us across the centuries as we contemplate Russia today, where St. Petersburg has become St. Petersburg again."I am older, madame, than the city where you reign," Voltaire wrote to Catherine the Great in 1765, when he was 70 years old. "I even dare to add that I am older than your empire." He dated its rise from the reign of Peter the Great, regarded Russia as the international prodigy of his own lifetime, and therefore as his own titanic contemporary.Voltaire was born in 1694, and the approaching occasion of his 300th birthday next week will be marked in France, and all over Europe, by an attempt to come to terms with his monumental significance for the 18th century and for ours as well. Voltaire's own vast empire of plays, fables, letters, histories, poems and polemics made him, too, a power to be contemplated with awe and amazement. One still catches one's breath at the dazzling irreverence of the "Philosophical Dictionary," in which he alphabetically, blasphemously, comically revised anything and everything from atheism, baptism and circumcision to torture, transubstantiation and virtue.What made him the first modern intellectual was his refusal to recognize any subject as off-limits, his readiness to write about whatever excited his anger or admiration, his contempt or curiosity. He was also the first of many modern intellectuals to take Russia as his subject "almost unknown to us until then," he wrote to make of it a lifelong fascination and to demand that his contemporaries recognize its overwhelming importance. Voltaire was a child when Peter built his fleet, traveled incognito to Holland and England to learn about the world outside Russia and began to build the city of St. Petersburg on the marshes by the Gulf of Finland. Voltaire was a young man in 1717, when Peter's visit to Paris created the kind of sensation that other Russian leaders have also excited, even in our own times, in going abroad.Catherine’s manifesto would become great literature in abstract but difficult to enforce in practice. “She created eighty provinces in which she allowed a limited measure of democracy and permitted the local gentry to elect the councilors of the district director. As for foreign policy, her activity led to successful wars against Turkey which created better trade routes on the Black Sea. Diplomatically, Russia’s presence and importance to the West grew with key acquisitions such as the colonization of Alaska. Catherine subsequently became obsessed with new legislation of civil and moral order which became known as “legislomania.” Immigration and economic growth was increased “equaling some of the highest rates of expansion in preindustrial Europe.Aside from politics, “Catherine saw the need for greater education in Russia.” Academies for the arts, sciences, women and medicine were completed during her reign. During this time, Catherine did not remarry. “Unlike male rulers, she could not remarry or be allowed a consort for fear, one assumes, of polluting the imaginary male line.This proposal of bias against women’s sexual relations is an important device in modern politics. It is known that Catherine had twelve lovers between 1752 and her death including Sergei, the proposed father of the heir, Paul. Orlov and Poniatowksi are both suspected to be fathers to her two other children as well. Paul lived away from the court and her daughter was also forgotten. Mostly, Catherine ruled alone.

Catherine’s predication of Voltaire as “so good a Russian” indicates something inherently intimate. They only communicated through letters, and as it was pointed out above, it was Diderot who went to Russia to visit her court, not Voltaire. Strangely enough, however, Voltaire in another letter emphasizes that his dying wish was to be buried in Russia, writing “why should I not have the pleasure of being buried in some corner of Petersburg, where I could see you pass to and fro under your arches of triumph, crowned with laurel and olive?”

Catherine’s predication of Voltaire as “so good a Russian” indicates something inherently intimate. They only communicated through letters, and as it was pointed out above, it was Diderot who went to Russia to visit her court, not Voltaire. Strangely enough, however, Voltaire in another letter emphasizes that his dying wish was to be buried in Russia, writing “why should I not have the pleasure of being buried in some corner of Petersburg, where I could see you pass to and fro under your arches of triumph, crowned with laurel and olive?”