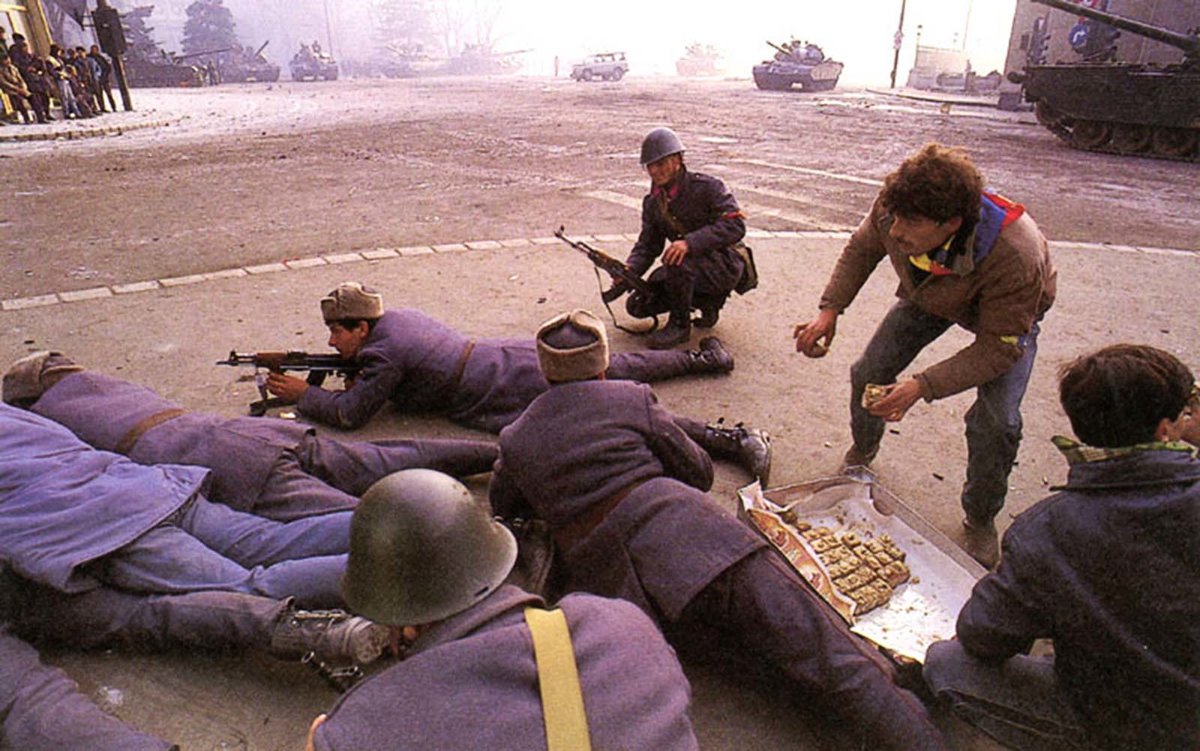

THE 1989'S ROMANIAN REVOLUTION, THE COMMUNIST NICOLAE CEAUSESCU WAS A ROMANIAN DICTATOR ,RULED THE COUNTRY ABOUT 24 YEARS.NICOLAE AND HIS WIFE ELENA WERE EXECUTED BY FIRING SQUAD.

Nicolae Ceausescu became a megalomaniac dictator, ruthless and surrounded himself blindly by people who were trying to take advantage of his power. He started huge expensive constructions like The People’s House and he had this ambition to pay all Romania’s external debt. But all came with a great price. The people got poorer and their life became miserable. The Romanian people were starving, had no link to the world outside the Russian borders and had rationalized heat, gas and water into their homes. Above that, the secret service of the communist regime, named “Securitate”, was watching everybody’s moves and punished everything they considered to be a threat to the regime.

Nicolae Ceausescu became a megalomaniac dictator, ruthless and surrounded himself blindly by people who were trying to take advantage of his power. He started huge expensive constructions like The People’s House and he had this ambition to pay all Romania’s external debt. But all came with a great price. The people got poorer and their life became miserable. The Romanian people were starving, had no link to the world outside the Russian borders and had rationalized heat, gas and water into their homes. Above that, the secret service of the communist regime, named “Securitate”, was watching everybody’s moves and punished everything they considered to be a threat to the regime.

On

22 December 1989, Romania's communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu was

overthrown in a violent revolution and fled from the capital, Bucharest.

Three days later, he and his wife Elena were executed by firing squad.

It was the last of the popular uprisings

against communist rule in eastern Europe that year.After the euphoria

of Solidarity's victory in free elections in Poland and the Velvet

Revolution in Prague, this was different. The Romanian revolution was

the last, and the bloodiest, in the whole region. It came to a head on

Christmas Day, when the dictator and his wife were executed.Two days

later, video pictures of their summary trial and execution were shown on

television in Romania and around the world. Ten years on, conspiracy

theories still abound, suggesting that many of the key events were

stage-managed by enemies of democracy - that the Romanian revolution was

not a revolution at all, but rather a coup d'etat.In 22 December

1989, Bucharest’s stolid Central Committee building had been an

impenetrable seat of communist power for decades. Then, on that day,

hundreds of ordinary Romanians armed only with stones and courage surged

past troops and stormed inside.There could be no clearer sign that the

regime’s grip on its cold, hungry, deprived people had been broken.

Dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena raced for a helicopter

waiting on the roof, as bewildered as they were scared. His 25-year

control of the country had been complete and paranoid. Children who

presented flowers at official events had to spend days in quarantine

first, portraits that only showed one of his ears were banned, and

dissidents were jailed or worse.As communist governments collapsed

across Europe, Ceausescu looked set to ride out the wave of longing and

discontent, fuelled by clandestine reports on change elsewhere, until a

standoff with a dissident priest in western Romania triggered his

downfall.On 17 December troops fired on crowds that had gathered to stop

pastor Laszlo Tokes being evicted from his home. Dozens were killed and

news of the brutality whipped through Romania, sparking protests in

other cities. Within a week Ceausescu had vanished from Bucharest and

from power, his departure stunning a country that for so long had bent

to his will. His reappearance in TV news reports three days later, as an

executed convict, was almost as shocking. The image of Romania’s

communist despot reduced to a crumpled, bloody corpse was beamed across

the world, apparently a triumphant declaration of all-out revolution.

Fast forward 25 years and the verdict on what happened next is, at best,

mixed. Many argue that the execution of the Ceausescus was a false

dawn. The show trial was organised by fellow communists, who twisted a

popular uprising into little more than a palace coup and held on firmly

to the levers of power.Prominent at the start of the revolution, he

called for senior communists to be blocked from office in Romania, but

was sidelined after asking the man who went on to become president: “Who

are you and what have you been doing the last five years?”That man, Ion

Iliescu, and other former communists ran the government for years and

still sit in parliament. Former members of the security forces and their

families have got rich from privatisation and there has been no justice

for the regime’s former victims.Romania was one of Europe’s few former

Soviet bloc countries that did not pass a “lustration” law to ban senior

communists from holding office in the new government.For

his 24 years as communist party leader - 21 of them as Romania's

president - Nicolae Ceausescu kept up a reign of fear, suppressing all

opposition with the help of the brutal secret police, the Securitate,

with the largest network of spies and informers

in Eastern Europe.At home he encouraged an extreme kind of personality

cult among the population. He skilfully exploited his policy of

independence from Moscow within the communist bloc to bolster his

position at home and abroad.

Ceausescu was a master at playing off

the world powers against each other during the Cold War. But when

Gorbachev's perestrioka reforms took hold, and one by one the countries

of the Warsaw Pact claimed their freedom, his world fell apart.His

downfall came as a result of his violent overreaction to public unrest

over local issues such as food shortages.It began on 15 December with

demonstrations in the western city of Timisoara against the harassment

of a dissident ethnic-Hungarian priest, Laszlo Tokes.These soon swelled

into a mass protest, in which slogans like "We want bread" soon turned

into "Down with Ceausescu".Ceausescu was away on a visit to Iran at the

time, but when he heard of this open challenge to his power he is said

to have gone into a blind rage.He railed against what he thought was a

plot against him, orchestrated jointly by the Russians and the

Americans. He denounced the army and Securitate generals who had ignored

his orders to shoot protestors, and personally ordered troops to fire

on the Timisoara demonstrators.On

17 December they did so, and initial reports suggested many hundreds

had been killed. In fact the number of dead was probably fewer than 100,

but mass protests quickly spread to many cities, including

Bucharest.Ceausescu sought to restore his own authority

on 21 December by stage-managing a show of support for his government,

as he had often done before, in Bucharest's main square. But the ploy

went disastrously wrong when the crowds interrupted his speech, jeering

at Ceausescu live on television.Parts of the army as well as the

Securitate, which had been built up as Ceausescu's private army, were

still loyal. But Ceausescu's fate was sealed when senior army generals

as well as communist party figures turned against him.Priest Laszlo

Tokes became a public icon Priest Laszlo Tokes became a public iconAmid

bloody street battles on 22 December, an angry mass of people stormed

Ceausescu's offices. He fled by helicopter, but was seized outside the

city. In a summary court martial held in secret, Nicolae and Elena

Ceausescu were accused of ordering the deaths of 60,000 people, and on

Christmas Day they were shot "like dogs".Anti-Ceausescu forces within

the power elite made sure the couple was swiftly put to death. And when

pictures showing their dead bodies, riddled with bullets, were

broadcast, the street protests subsided.Within a few days the so-called

National Salvation Front, headed by a then little-known communist figure

Ion Iliescu, had assumed power and announced the abolition of the

one-party system. Iliescu and his allies were to stay in power until

1996.But rather than carrying out through democratic reforms, successive

Romanian governments blocked attempts to prosecute those responsible

for the bloodshed of 1989; while much economic power stayed in the hands

of shadowy figures from the old regime.For the past three years

Romania's rulers have been committed to democratic change, and a

faltering process of democratisation has gone forward.Recently many of

the extravagant gifts the Ceausescus received from world leaders were

auctioned off to the public, to try to dispel memories of their

megalomaniac rule.But their dark influence has proved so strong that 10

years after their deaths, the people of Romania are still trying to

overcome the legacy of mistrust and secrecy of the Ceausescu years.

Elena

Ceaușescu was a Romanian communist politician who was the wife of

Nicolae Ceaușescu, President of the Socialist Republic of Romania. She

was also the Deputy Prime Minister of Romania.She

joined the Bucharest branch of the Romanian Communist Party in 1939 and

met 21-year-old Nicolae Ceaușescu. Ceaușescu was instantly attracted to

her which, reportedly, made him never look at another woman in a

romantic manner.[3] Their relationship was interrupted by Ceaușescu's

frequent stints in prison, but they finally married on 23 December 1947.

Elena

Ceaușescu was a Romanian communist politician who was the wife of

Nicolae Ceaușescu, President of the Socialist Republic of Romania. She

was also the Deputy Prime Minister of Romania.She

joined the Bucharest branch of the Romanian Communist Party in 1939 and

met 21-year-old Nicolae Ceaușescu. Ceaușescu was instantly attracted to

her which, reportedly, made him never look at another woman in a

romantic manner.[3] Their relationship was interrupted by Ceaușescu's

frequent stints in prison, but they finally married on 23 December 1947.

On the morning of 21 December Ceausescu addressed an assembly of approximately 100,000 people, to condemn the uprising in Timișoara. Party officials took great pains to make it appear that Ceausescu was still immensely popular. Thousands of workers were bussed into the square under threat of being fired. They were given red flags, banners and large pictures of Ceausescu and his wife. The crowd were given orders on where to stand, when to applaud and what to sing. The front rows of the assembly were made up of low-level Communist Party officials and members who acted as cheer-leaders.Ceausescu blamed the Timișoara uprising on “fascist agitators”. However, Ceausescu was out of touch with his people and completely misread the crowd’s mood. The people remained unresponsive, and only the front rows supported Ceausescu with cheers and applause. Eight minutes into the speech, some in the crowd actually began to jeer, boo, whistle and utter insults at him. In response, Ceausescu raised his right hand in hopes of silencing the crowd; his stunned expression remains one of the defining moments of the end of Communism in Eastern Europe.The entire speech was being broadcast live around Romania, and it is estimated that perhaps 76% of the nation was watching. Censors attempted to cut the live video feed, and replace it with Communist propaganda songs and video praising the Ceausescu regime, but parts of the riots had already been broadcast and most of the Romanian people realized that something unusual was in progress. His security guard appeared, disappeared and, finally, hustled Ceausescu off the balcony. At that very moment, many everyday Romanians saw the weakness of Ceausescu’s regime for the first time.“It is as if, in that moment, everyday Romanian’s saw the possibility, saw the reality of the weakness of Ceausescu’s regime”, according to the Center for History & New Media. “Those moments of Ceausescu’s weakness and the power of popular pressure explain why, a mere 48 hours later,Ceausescu was attempting to flee Romania, all power lost".The following day, violence erupted on the streets of Bucharest. Senior generals gave up their support for Ceausescu, and the remaining loyal sections of the army and Securitate were overrun. At approximately 09:30 on the morning of December 22, Vasile Milea, Ceausescu’s minister of defense, died under suspicious circumstances. A communique by Ceausescu stated that Milea had been sacked for treason, and that he had committed suicide after his treason was revealed. The most widespread opinion at the time was that Milea hesitated to follow Ceausescu’s orders to fire on the demonstrators, even though tanks had been dispatched to downtown Bucharest that morning. Milea was already in severe disfavor with Ceausescu for initially sending soldiers to Timișoara without live ammunition. The rank-and-file soldiers believed that Milea had actually been murdered, and went over virtually en masse to the revolution. The senior commanders wrote off Ceausescu as a lost cause and made no effort to keep their men loyal to the regime. This effectively ended any chance of Ceausescu staying in power.As crowds stormed Communist Party headquarters, senior officials directed the Ceausescus to escape by helicopter; the shaken couple was said to be carried aboard by bodyguards shortly after noon. The helicopter was forced to land before it could reach its intended destination because of reports that the army would shoot it down.What happened was a groundswell of protest, quite spontaneous, in which Ceausescu was shouted down by the hundreds of thousands of people who 305 had been summoned, bused in as they always were to these events to be the passive witnesses to this repetitive call to national unity and follow-the-leader. He was in fact shouted down. He ended up retreating back from the balcony, while the police and security forces stepped in and quelled an incipient civil protest for the first time in anybody’s memory. This happened about six or eight weeks before the roof ultimately collapsed in December.After this national day surprise, the embassy started to gear itself up for what could be more of the same. There emerged a general consensus on the desk, in the analytical community and from embassy reporting that unlike the rest of Eastern Europe, if anything happened in Romania it would not be evolutionary or nonviolent because it was no basis for an evolutionary, nonviolent transition in the Romanian context. It was either going to be more of the same, and we were still betting that it was going to be more of the same, or it was going to be violent and nobody was prepared to predict how that might turn out.When there was a protest,it started out in Timisoara, which was the far western provincial capital, a multi-ethnic part of Romania near the Yugoslav border. There were a lot of Hungarians, a lot of Serbs.The police and the army were nowhere to be seen and the original protesters had by that time also dispersed. Iliescu went on national television, appealing to people to come to Bucharest to prevent "fascist extremists" from overthrowing the government.The next morning, thousands of coal miners descended on the city. Armed with clubs, chains and sledgehammers, the miners attacked the university, beating students and professors. The headquarters of opposition political parties were also ravaged.Iliescu thanked the miners, calling them patriots. To this day, he credits them with saving his government. In an interview with RFE/RL, he glossed over the havoc the miners inflicted.Victor Stanculescu, an agile former Romanian general who arranged the escape of the Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989, then joined the insurgent government and engineered Mr. Ceausescu’s trial and execution three days later.General Stanculescu (pronounced stahn-kul-ESS-ko) was first deputy defense minister when he was dispatched by Mr. Ceausescu to Timisoara, in western Romania, to suppress a pro-democracy protest.But after ordering security forces to fire on unarmed dissidents on Dec. 17, 1989, Mr. Ceausescu, the country’s last Communist leader and its brutally Stalinist head of state for two decades, lost control of his army as the revolt spread. Nearly 100 civilians were killed in Timisoara alone.

Nicolae Ceausescu ,his wife Elena and daughter Zoia Ceaușescu. Nicolae

Ceausescu was one of 10 children of a peasant farmer from a village in

the south of Romania. Aged 11 he ran away from home to escape his

drunken and abusive father to work as a shoemaker in the capital. From

there he was introduced to the then illegal Communist Party and the

young Ceausescu was arrested and jailed on several occasions for his

activism.

Nicolae Ceausescu ,his wife Elena and daughter Zoia Ceaușescu. Nicolae

Ceausescu was one of 10 children of a peasant farmer from a village in

the south of Romania. Aged 11 he ran away from home to escape his

drunken and abusive father to work as a shoemaker in the capital. From

there he was introduced to the then illegal Communist Party and the

young Ceausescu was arrested and jailed on several occasions for his

activism.

Romania under Nicolae Ceausescu’s communist regime Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena ruled the country for 24 years, from 1965 until 1989. During those years, Romania underwent several changes, and the population had to endure an endless number injustices and restrictions. Generally, historians present the Romanian Communism in two segments: one between 1965 and 1971, and one between 1971 and 1989.But the couple's three children have constantly expressed doubts their parents were actually buried in the graveyard in Ghencea, western Bucharest.They have fought a long-running battle for the remains to be exhumed, claiming there was no paperwork to prove they were in fact buried there.Ceausescu maintained an independence from the Soviet Union that was unparalleled in the Eastern Bloc. In the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries began to liberalize, Ceausescu maintained his hardline policies. In 1981, Ceausescu began an austerity program designed to enable Romania to liquidate its entire national debt ($10 billion).Ceausescu launched an offensive against the cultural autonomy and desired to return to the strict guidelines of socialist realism by directly attacking all of its opponents. This period was characterized by an increasingly erratic personality cult, extreme nationalism, and the deterioration of foreign relations with Western Europe and the Soviet Union. All activities were strictly controlled by the Party activists, and massive campaigns of population indoctrination began.In 1972, the members of the Ceausescu family were placed in key political positions, and Elena Ceausescu made her political debut one year later. Soon after, she became the second most powerful authority of the state. Romania recorded a drastic decline at the end of the 1980s when Ceausescu decided to pay all of the external debt of the country. This led to a severe austerity for the Romanian citizens, and to a massive decrease in living standards.As food shortages became common, the Party introduced cards for a strict supervision of food stocks. Sugar and oil limitations differed depending on population groups: higher ratios were given to people living in the urban areas and smaller ratios were given to the rural residents. Bread was sold in limited quantity, and could only be purchased from the place where one was domiciled.In October 1981, a restrictive decree stated that those who purchased basic food products in quantities exceeding the needs of one-month household consumption will be imprisoned for six months to five years.The secret police, Securitate, had become so ubiquitous as to make Romania essentially a police state. Free speech was limited and opinions that did not favor the Communist Party were forbidden. Even by Soviet bloc standards, the Securitate was exceptionally brutal.The Ceausescus’ killing showcased a disregard for the rule of law that continued for many years. When change came, in part under pressure from the European Union, it was focused on tackling corruption in the post-communist era. “If there are so many victims yet to find justice, there is no rule of law,” says General Dan Voinea, prosecutor at the Ceausescus’ trial, who later forged an unexpected career seeking justice for more than 1,000 people killed in the “revolution”.He is unrepentant about his role in what he insists was rough but real justice for a dictator with blood on his hands, and managed to secure the convictions of a handful of leaders for ordering troops to fire on protesters and other crimes during the revolution.As time passes, victims and perpetrators of crimes dating to the 1950s are dying. The hopes of those who wanted to see someone pay for the death of a parent, the torture of a spouse or other mistreatment were raised when the European court in Strasbourg ruled that there was no statute of limitations on crimes against humanity.But the Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and Memory of the Romanian Exile, which is meant to be spearheading efforts to hold historical abusers to account, has not got far. A list of nearly 170 potential targets for prosecution, published in 2007, has so far produced no convictions. A single trial finally began this autumn, but is proceeding at a glacial pace. “Nobody was ever convicted,” says the institute head, Cosmin Budeanca. “A few cases are open in front of prosecutors, but we need political will for something to happen.”A political appointee himself, critics say Budeanca is happy to drag his feet. He insists he is boxed in by lack of resources and intransigence from government officials unenthusiastic about revisiting the past. “Politicians’ resumés start from the 1990s, because what came before was not comfortable to present to the population,” he says.There are no prosecutors who specialise in crimes against humanity, he says, and there is a staff of only 36 to fight the bureaucracy. The justice ministry archives are out of bounds and interior ministry and former security service archives restricted.One aspect is a growing nostalgia for Ceausescu’s rule, including among Romanians who were spared rationing, propaganda and political controls.The deprivations included government-controlled neighbourhood central heating systems that kept whole blocks of flats at less than 10 degrees during frigid winters, and queues for food at department stores that started around 2am, even though people had no idea what they were waiting to buy.

Demonstrations

began in the western city of Timisoara against the harassment of a

dissident ethnic-Hungarian priest, Laszlo Tokes.It

led to protests about a lack of basic supplies such as bread but the

backlash from Ceausescu's armed forces led to accusations many people

were massacred.Demonstrators

stormed Ceausescu's palace and he and his wife tried to flee Bucharest

but they were captured by military forces who had turned against them.

Demonstrations

began in the western city of Timisoara against the harassment of a

dissident ethnic-Hungarian priest, Laszlo Tokes.It

led to protests about a lack of basic supplies such as bread but the

backlash from Ceausescu's armed forces led to accusations many people

were massacred.Demonstrators

stormed Ceausescu's palace and he and his wife tried to flee Bucharest

but they were captured by military forces who had turned against them.Ceausescu had built an empire on his own. The internal Stalinist dynamic if you will did not depend upon Soviet might. The Secret Police were an ever-present glue that kept Romanian society in place. Ceausescu, who had never bowed to events that had gone on in the rest of the Bloc, was not about to do so again.Bucharest was always bleak. They burn a lot of soft coal and in the wintertime the environment was sooty and murky 24 hours a day. The fact is that the Ceausescu regime deprived the population of all of the basic comforts, heat and light in the dark days of winter and certainly any kind of quality food products on the shelves.It was a terribly depressing environment.One of Ceaușescu’s dream was for Romania to reach a number of 20 million inhabitants. Thus, in 1966, he declared abortion illegal. As a result, between 1966 and 1989, over ten thousand women died from abortions performed in secret using improvised tools such as coat hangers. The whole phenomenon was however ignored by the Party, and instead, the title of “Heroic Mother” was awarded for women who had at least 10 children.Despite living in these harsh conditions, criticizing the Party was close to impossible, as whoever dared speak against the Communist regime was severely punished by the Department of State Security. The Securitate was the secret police agency of the Socialist Republic of Romania, and it closely monitored all Romanian citizens, especially the ones with foreign connections. Leaving the country was also a far-away dream for most of the citizens. Those who tried it risked many years of prison and torture. Going to church was also illegal, and the trust between friends or family was basically non-existent, as anyone could have been a member of the secret police.An attempt by police in June to violently disperse the crowd led to several minor clashes. But then, something unusual occurred. Groups of young men arrived and began setting fire to police cars and ransacking shops.The worst excesses of the Ceausescu regime were indeed gone: the authorities no longer mandated how many light bulbs could be used in each house, how many children a woman should have or which conversations had to be reported to the secret police. But intimidation and occasional violence remained tools of the government. Loud dissent was met with truncheons, uncomfortable questions about the past hushed up and any serious political opposition stifled.Ceausescu was a big fan of Kim Il-Sun and his “Cult of Personality”, eventually implementing a lot of N. Korean type changes to the way he and his family ran the country. The spectacularly corrupt and autocratic regime of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu. As with most, if not all dictatorships, power was maintained using the services of a brutal secret police, in Romania's case, the Securitate. Stalin once said that, "power alone is not enough, you need to gain prestige", this was very much the case for Elena. Her way to gain prestige and respectability was to be seen to excel in the fields of chemistry and chemical engineering.On the path to respectability Elena had to have a PhD, so a thesis was duly produced for and attributed to her - but there was a problem. By Romanian law the candidate for a doctoral thesis had to subject his or her work to public scrutiny by giving a presentation. She overcame this by quickly changing the law thus removing the requirement - absolute power does have its benefits.The unbelievable mismanagement of the Ceausescu regime over 24 years brought food shortages, routine torture, hundreds of executions and most famously, state neglect of orphans and handicapped children. This generated so much anger within Romania that when the regime collapsed the end was swift. Within an hour Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu had been tried, put against a wall and shotThe Ceausescu regime began to fall apart when despite the threat of reprisals from the Securitate, demonstrators amassed on the streets of the provincial city of Timisoara in unprecedented numbers, protesting against the regime.When democratic forces regained the upper hand and President Emil Constantinescu replaced Iliescu in 1996, many hoped things would finally change. Constantinescu, the rector of Bucharest University, was supported by many of the dissident intellectuals who had found themselves outmaneuvered by Iliescu in the first weeks of the 1989 revolution. An investigation of the events of 1989 and 1990 as well as a break with Iliescu's policies were key planks in his electoral platform.The trial of Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu was a short trial held on 25 December 1989 by an Exceptional Military Tribunal, a drumhead court-martial created at the request of the Council of the National Salvation Front, resulting in the death sentence and execution of former Romanian President and General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife, Elena Ceaușescu.Officially, Ceausescu and his wife were executed for their roles in the murders of some 70,000 people who had opposed their rule. This happened following a brief trial - not exactly “impartial” but it was, at least, a trial.The executions of Ceasescu and his wife were broadcast live on television, immediately showing any pro-Ceausescu forces that there was no need to continue to resist. So for many Romanians, yes, it was definitely necessary to put that era to an indisputable end.