VENEZUELA UNDER RIGHT WING LEADERS ,HUGO CHAVEZ AND NICOLAS MADURO : " HOW VENEZUELA WENT FROM A RICH DEMOCRACY TO A DICTATORSHIP ON BRINK OF COLLAPSE.VENEZUELAN DEBT AND POLITICAL CRISIS UNDER PRESIDENT NICOLAS MADURO'S EFFORTS TO CONSOLIDATE POWER AMID A DEEPENING ECONOMIC AND HUMANITARIAN CRISIS".

Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez has died of cancer at 58 in Caracas, here's five facts about Nicolas Maduro, Chavez's successor. From Bus Driver to Minister of Foreign Affairs: Maduro, born on November 23, 1962, went from bus driver to union leader to congressman to foreign minister and now to president.Maduro is married to Cilia Flores, a prominent lawyer within Chavez's Fifth Republic Movement, who became the first woman to serve as president of the National Assembly in 2006 and is now the country's Attorney General.Maduro, one of the founders of the Fifth Republic Movement (MVR), is credited with securing Chavez's release from prison in 1994 after his unsuccessful coup d'etat in 1992. Maduro accused "the domestic and foreign enemies of Venezuela" of somehow infecting Hugo Chavez with cancer. He also expelled a U.S. Embassy diplomat who Maduro said was seeking military support for a plot against the government. Chavez's endorsement of Maduro alienated Diosdado Cabello, a powerful Socialist Party official with ties to the armed forces, who had been considered another top candidate as the strongman's successor. During his youth, Chávez dreamed of becoming a famous baseball player. His hero was Venezuelan pitcher Néstor Isaías "Látigo" Chávez . He instead enrolled in a military academy to become a soldier.In February 1992, Chávez organized a failed coup against then President Carlos Andrés Pérez. Chávez spent more than two years in prison before being granted a pardon.In December 1998, Chávez won Venezuela's presidential election with 56 percent of the vote.When Chávez visited the United States in June 1999, he threw the opening pitch at a Mets baseball game and rang the closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange.On April 11, 2002, Chávez was briefly ousted by an attempted coup. He regained the presidency three days later and accused the United States of backing the failed coup.In 2007, a constitutional referendum failed that would have allowed for Chávez to be re-elected infinitely. In 2008, a second referendum vote ending presidential term limits passed.The foreign policy of the Hugo Chávez administration concerns the policy initiatives made by Venezuela under its former President, Hugo Chávez, towards other states. Chávez's foreign policy may be roughly divided into that concerned with United States-Venezuela relations and that concerned with Venezuela's relations with other states, particularly those in Latin America and developing countries on other continents. In many respects the policies of the Chávez government were a substantial break from the previous administrations that governed Venezuela. Hugo Chavez’s Failed Socialist Experiment Is Deadlier Than Ever.Hugo Chávez had barely been in office two months when Nelson Chitty La Roche, a burly, gruff, gun-toting lawmaker from the Venezuelan political establishment, told me he was fed up. Chitty didn’t care for the way the young socialist leader was pushing around Congress and threatening to rule by decree, and he let out, somewhat flippantly, that he was starting to map out plans to have him impeached.It was an absurd notion. In those heady, early days of the regime, Chávez was wildly popular. Polls showed he had the support of about 80 percent of the population, an estimate that, if anything, struck me as low. He was their showman, their savior, their avenger the man who would speak for them and fight for them and provide for them.Trying to drive him out of power then would have caused a wicked backlash. And yet here was a high-ranking lawmaker talking openly about such a possibility, giving voice to a notion I’ve heard countless times since that the Chavistas’ days are numbered, that the regime is bound to collapse under the weight of its own incompetence.Dec. 6 marks the 20th anniversary of the landslide electoral victory that first brought Chávez to power. And, amazingly, his socialist government still stands. (Nicolás Maduro took over as president upon Chávez’s death five years ago.) So when I hear chatter about the imminent demise of the regime, it leaves me somewhat cold.Sure, the place seems ripe for change. Even from my vantage in the U.S., where the trauma of a kidnapping in Venezuela still haunts my family, the excruciating crisis the Chavistas have engendered is plain to see: the hyperinflation, the starvation, the epidemics. Talk of a military coup swirls constantly; international sanctions are hamstringing top officials; and neighboring governments, now in the hands of right-leaning leaders, are growing increasingly impatient with Maduro’s inability to control the flood of migrants pouring into their countries.But this regime, through guile and brute force, has managed to overcome any number of existential challenges before. Under Chávez all of the obvious indicators moved in the right direction. Poverty was halved. Extreme poverty almost disappeared. Unemployment fell dramatically. Inequality was lowered at last. Calorific intake rose. Illiteracy was eradicated. Millions achieved access to free medical services for the first time. And political inclusion was boosted by voter-registration drives, with a knock-on effect on turnout in elections.But the most significant change was less tangible, as Chávez attempted to shift the national ideal away from crude and conspicuous aping of western consumer capitalism towards greater confidence in local culture, character and capability. Abroad, Chávez promoted stronger relations among developing countries to curb the influence of major powers and international financial institutions. He fought the spread of neoliberal free-trade agreements that prioritised corporate interests over social wellbeing and democratic control. And he routinely spoke up for those weaker countries subjected to the violent whims of the strong.

His critics argue that Chávez is merely expropriating property in a Robert Mugabe-style land grab. (No doubt Mugabe is flattered by the allusion.) But Chávez has declared it a ‘war on the latifundio’ (or rich estate owners), casting himself as a latterday Robin Hood of the Amazon Forest.No doubt few Venezuelans appreciated that Chávez was a bigger crook than any drug lord who ever menaced Latin America. Yet he earned his rightful place in the rogue’s gallery of dead kleptomaniacs, which includes everyone from Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier of Haiti to Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire/DR Congo and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya. Crime bosses like Al Capone and drug lords like Pablo Escobar had nothing on political dictators.

His critics argue that Chávez is merely expropriating property in a Robert Mugabe-style land grab. (No doubt Mugabe is flattered by the allusion.) But Chávez has declared it a ‘war on the latifundio’ (or rich estate owners), casting himself as a latterday Robin Hood of the Amazon Forest.No doubt few Venezuelans appreciated that Chávez was a bigger crook than any drug lord who ever menaced Latin America. Yet he earned his rightful place in the rogue’s gallery of dead kleptomaniacs, which includes everyone from Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier of Haiti to Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire/DR Congo and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya. Crime bosses like Al Capone and drug lords like Pablo Escobar had nothing on political dictators.

In the Chavista era, the government has only had control over its state oil company, its main source of export revenue and hard currency, since about 2003, four years after the late Hugo Chavez was first took office. It took South Korea, a country not regarded as an ideological threat to the imperial powers, about 40 years to achieve the living standards of a rich country. It took Cuba about forty years to achieve a lower child mortality rate than the United States a rich country that is a notorious laggard by that measure.People who care about the success of progressive change in Venezuela and in Latin America must do all they can to ensure that huge self-inflicted problems are avoided. Progressive governments will face extreme hostility abroad and at home during the best of times. They can least afford to make such serious mistakes.

In the Chavista era, the government has only had control over its state oil company, its main source of export revenue and hard currency, since about 2003, four years after the late Hugo Chavez was first took office. It took South Korea, a country not regarded as an ideological threat to the imperial powers, about 40 years to achieve the living standards of a rich country. It took Cuba about forty years to achieve a lower child mortality rate than the United States a rich country that is a notorious laggard by that measure.People who care about the success of progressive change in Venezuela and in Latin America must do all they can to ensure that huge self-inflicted problems are avoided. Progressive governments will face extreme hostility abroad and at home during the best of times. They can least afford to make such serious mistakes.

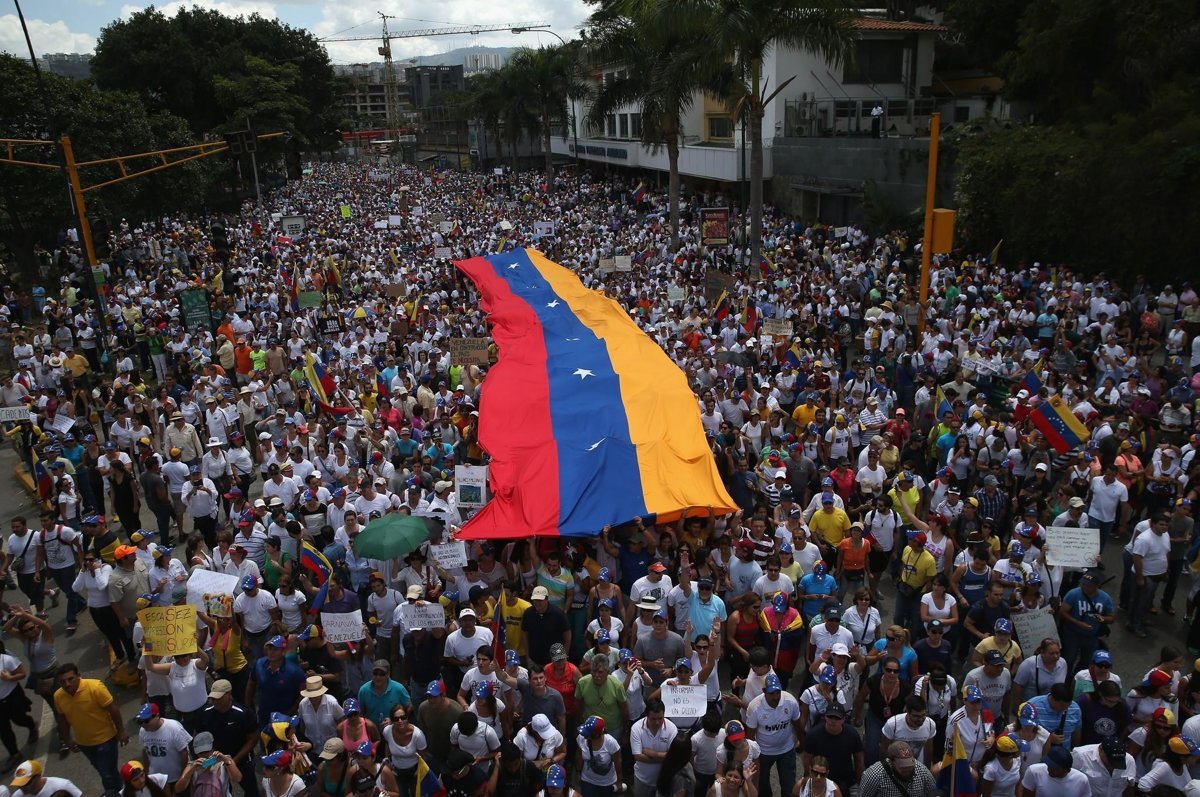

Have those who state that Nicolás Maduro is a dictator, a usurper, and that the 2019-2025 presidential period lacks legitimacy.This opinion was first advanced by the 12 Latin American countries that make up the Lima Group. Their statement reads: “The electoral process carried out in Venezuela on 20th May 2018 lacks legitimacy in that it didn’t have the participation of all Venezuelan political actors, nor the presence of independent international observers, nor the international guarantees and standards needed for it to be a free, just, and transparent process.The leaders of the Venezuelan opposition, the non-democratic ones, repeat ceaselessly, and without arguments, that Maduro is a usurper.It was the Venezuelan opposition that requested an early election. It was held in May rather than December, as is tradition, because the opposition asked, during a dialogue with the government held in the Dominican Republic, for it to be conducted in the first term of 2018.In Venezuela voting is a right, but not compulsory. Those who freely, although influenced by undemocratic political organisations that called for abstention, decided not to vote had every right to do so. But in no way does this delegitimise the electoral process, especially when this would imply disregarding the 9,389,056 people who decided to vote and exercised democratically their right to suffrage.Sixteen political parties participated in the electoral contest, including governing PSUV and the MSV, Tupamaro, UPV, Podemos, PPT, ORA, MPAC, MEP, PCV, AP, MAS, Copei, Esperanza por el Cambio, and UPP89.In Venezuela it is not compulsory that all political parties participate in electoral processes. It is their right to choose whether to participate or not. That’s exactly why our system is democratic. The fact that three parties (AD, VP, and PJ) decided freely not to participate does not delegitimise the electoral process.Six candidates competed for presidency: Nicolás Maduro, Henri Falcón, Javier Bertucci, Reinaldo Quijada, Francisco Visconti Osorio and Luis Alejandro Ratti (the last two later decided to withdraw.Maduro won by a wide margin, obtaining 6,248,864 votes, that is 67.84%; followed by Henri Falcón with 1,927,958, or 20.93%; Javier Bertucci with 1,015,895, 10.82%; and Reinaldo Quijada, who obtained 36,246 votes, or 0.39% of the total. The difference between Maduro and Falcón was of 46.91 percentage points.Nicolás Maduro, the president of Venezuela, is scrambling to cling to power as his country is battered by an unprecedented economic crisis. And in the process, he’s becoming an autocrat.Maduro is tossing political opponents in prison. He is cracking down on growing street protests with lethal force, with government security forces killing at least 46 demonstrators in recent months. He has repeatedly postponed regional government elections in order to stave off threats to his party’s power. And in July he held a rigged election for a special legislative body that supplanted the country’s parliament the one branch of government that was controlled by his political opposition. The new superbody has carte blanche to rewrite the country’s constitution and expand his executive powers.Maduro and his supporters now have total control of the government, and they’re showing no signs of slowing down.It’s difficult to overstate how dire Venezuela’s economic plight is. The country entered a deep recession in 2014 spurred by the drop in global oil prices, and cumbersome regulations on its currency are helping produce record-breaking inflation. The International Monetary Fund estimates that prices in Venezuela are set to increase more than 700 percent this year. Seventy-five percent of the country’s population has lost an average of 19 pounds of bodyweight between 2015 and 2016 due to food shortages throughout the country.But Maduro has done everything he can to prevent swelling popular discontent from limiting his power. His tactics place him among a special league of democratic authoritarians like Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has used a referendum to expand the powers of his presidency, imprisoned political prisoners, attacked the judiciary branch of his government, and restricted free press in the wake of an attempted coup against him last year. Both leaders use crisis as a pretext for strengthening executive power while leaving the shells of their country’s democratic institutions intact.For the US, Maduro’s increasing authoritarianism and refusal to reform his economy represents a major geopolitical and humanitarian challenge. The country’s total collapse would cause chaos in Latin America, creating an exodus of refugees to neighboring nations and likely exacerbating high crime rates in Central America and the Caribbean. Thousands of Venezuelans are already fleeing to Colombia and, as of this year, Venezuelans top the list of asylum seekers in the US for the first time ever.So far, the Trump administration has tried using diplomatic and economic tools to pressure Maduro to drop his power grabs.But Maduro’s expanding control of Venezuela’s institutions should not be mistaken for an expansion of real power. As the country’s economic crisis deepens and he becomes more tyrannical, he is alienating his own political base, according to experts. And his increasing reliance on appointing members of the military to power in his administration shows he doesn’t have unilateral sway over the government. Maduro’s heavy-handed tactics mask his deep strategic weakness.Presidential elections in Venezuela are scheduled for next year, and a number of outcomes are possible. If they are actually held even somewhat fairly and the opposition unites in their participation in them, experts say it could be the end for Maduro and a blow to the political revolution that brought him into power. Or in the face of a united opposition Maduro could double down on his repression and push Venezuela even closer to dictatorship.

Oil-rich Venezuela has skidded into crisis as global crude prices have plunged since mid-2014, pushing Chavez and Maduro's socialist model to the brink.Venezuelans spend long hours lining up outside supermarkets and pharmacies only to find bare shelves and soaring prices inside. Shortages have triggered outbreaks of looting and riots.The country is facing its third year of deep recession this year, with inflation set to top 700 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund.In a country rife with economic and political turmoil, Venezuela President Nicolas Maduro seeks to provide renewed hope by holding what he describes as mega elections.

Oil-rich Venezuela has skidded into crisis as global crude prices have plunged since mid-2014, pushing Chavez and Maduro's socialist model to the brink.Venezuelans spend long hours lining up outside supermarkets and pharmacies only to find bare shelves and soaring prices inside. Shortages have triggered outbreaks of looting and riots.The country is facing its third year of deep recession this year, with inflation set to top 700 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund.In a country rife with economic and political turmoil, Venezuela President Nicolas Maduro seeks to provide renewed hope by holding what he describes as mega elections.

International capitalism rallies behind Venezuela’s right-wing opposition leaders.The social, political and economic crisis which is currently rocking Venezuela poses crucial questions and lessons for socialists and the international working class.The forces of international capitalism have rallied behind the declaration of the Venezuelan right-wing opposition leader Juan Guaidó who has declared himself the self-appointed ‘interim’ president. Abrams was convicted for his involvement in arming the ‘Contras’ – paramilitary forces in Nicaragua in the 1980s.Socialists and workers should have no truck with, nor lend any support to, the reactionary attempts at a coup carried out by these right-wing forces of reaction.Should these forces succeed, the repression and attacks Venezuelan workers and socialists are currently suffering will dramatically worsen. Any right-wing regime coming to power to replace Maduro will enact revenge on the working class and socialists.The hypocrisy of western imperialism knows no limits. They condemn the Maduro government but have collaborated and supported brutal regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America. This long list includes Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the military dictatorships in Chile, Argentina, Brazil and elsewhere to name but a few!Despite opposing these reactionary attempts to carry through a regime change, socialists cannot put any confidence or complete trust in the Maduro regime.An economic and social catastrophe is engulfing Venezuela. GDP collapsed by 35% between 2013 and 2017! This is a greater collapse than in the US depression between 1929 and 1933, when it fell by 28%. It is slightly higher than that experienced when the former USSR disintegrated in 1992 and capitalism was restored.The economic collapse in Venezuela has resulted in the wiping out of the gains in healthcare, education and other areas that were introduced previously by the Hugo Chávez-led government.Hunger and starvation have returned, and the social collapse is measured in the soaring crime rate in the major cities. In the largest refugee crisis in Latin American history, an estimated three million people have fled the country – about 10% of the population!The capitalist class and its political representatives internationally are using this devastating social and economic crisis to claim another ‘failure of socialism’.Venezuela was used in a ferocious campaign in Spain and Brazil to try and discredit socialism.Since the turn of the century, every big country in South America except Colombia has elected a socialist president at some point. Socialists have taken power in South America’s largest economy (Brazil), in its poorest (Bolivia) and in its most capitalist (Chile). Socialists have led South America’s most stable country (Uruguay) as well as its most unstable (Ecuador). Argentina and Peru elected leftists who, for various reasons, didn’t refer to themselves as socialists but certainly governed as such.Mysteriously, the supposedly automatic link between socialism and the zombie apocalypse skipped all of them. Not content with merely not-collapsing, a number of these countries have thrived.Take Peru. When Ollanta Humala, widely seen as one of the most radical hard-left leaders in the region, was elected president in 2011, 28 percent of Peruvians were poor. In office, Humala governed from the left, but sensibly, investing in the poor while nurturing economic growth. By the time he handed over power in 2016 (peacefully, to a right-wing successor), just 21 percent of Peruvians were poor.Economic activity has collapsed to near 40% year-over-year in the third quarter, though this is the best-case scenario. It is probably worse. Venezuela’s government is not as transparent as it used to be, so these are market estimates using all available economic data. Domestic oil and natural gas production are shrinking.The large scale protests witnessed in 2017 have ended. Instead, millions of people have fled on foot into Colombia and Brazil. Venezuela’s population is shrinking. Recently, a former top judge asked for asylum in the U.S. Could there be more this year if Maduro cracks down on the opposition and demands loyalty among political appointees?As Maduro enters yet another term, the real test of his strength is in how much pain Venezuelans can take. The economy is forecast to contract again this year. They have declining oil production, so PdVSA can’t be PSUV’s ATM machine. Some say they will get the money through illegal means. The U.S. has called senior members of PSUV narco-traffickers. Black market businesses could be one way of funding. Central bank reserves minus gold have to be heading to single digits this year. Venezuela also tried cryptocurrency as a funding mechanism, but there is little information on how the Petro coin has helped them.Venezuela has been turning into a dictatorship for the last two years.

Nicolas Maduro has warned world leaders at a Non-Aligned Summit that his country was being lashed by a US economic war aimed at toppling him.Speaking at the same event, which opened Saturday, Maduro’s closest regional ally, Cuban President Raul Castro, echoed the charge, despite his country’s thawing relations with the United States.“Venezuela is facing an onslaught ,that is against all of Latin America and the Caribbean, that is trying to re-impose and recolonize the politics, economy, culture and life of our countries,” Maduro , a socialist who has made the economy increasingly state-run charged in his speech after taking over the movement’s rotating presidency from Iran.

Nicolas Maduro has warned world leaders at a Non-Aligned Summit that his country was being lashed by a US economic war aimed at toppling him.Speaking at the same event, which opened Saturday, Maduro’s closest regional ally, Cuban President Raul Castro, echoed the charge, despite his country’s thawing relations with the United States.“Venezuela is facing an onslaught ,that is against all of Latin America and the Caribbean, that is trying to re-impose and recolonize the politics, economy, culture and life of our countries,” Maduro , a socialist who has made the economy increasingly state-run charged in his speech after taking over the movement’s rotating presidency from Iran.

Venezuela, named the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela since 1999, is located on the northern coast of South America. The country comprises a continental mainland and numerous islands in the Caribbean Sea. It borders Guyana to the east, Brazil to the south, and Colombia to the west. Its Caribbean neighbors off the northern coast are Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Curaçao, Bonaire, Aruba, Saint Vicent and the Grenadines and the Leeward Antilles. Falling within the tropics, Venezuela sits closer to the Equator, in the Northern Hemisphere.Venezuela is known widely for its petroleum industry, the environmental diversity of its territory, and its natural features. Home to a huge diversity of wildlife in a variety of protected habitats, Venezuela is considered to be among the 17 most megadiverse countries in the world. Venezuela is also among the most urban countries in Latin America. The majority of the population is concentrated in the north, especially in the largest metropolis, Caracas. Other major cities include Maracay, Maracaibo, Barquisimeto, Valencia, and Ciudad Guayana.The governments of Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and St. Lucia. Most of these governments are themselves involved in massive corruption, violent suppression of dissent, or both.The right-wing government of President Mauricio Macri of Argentina is battling labor unions in the streets as it cuts social welfare to the bone, yet the Argentine economy is seen by many as at the point of collapse.The extremely unpopular Brazilian government of President Michel Temer of Brazil took power in an illegal coup and is widely considered illegitimate by Brazilians. Temer’s government just engineered, by means of a kangaroo court proceeding, the imprisonment and deprivation of political rights of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was far ahead in the polls to win the presidency again in elections later this year.In Colombia, social justice activists are being murdered by death squads, and opposition leaders face state repression. In Guatemala, the indigenous population, a majority by some criteria, continues to be oppressed by the corrupt and undemocratic government of President Jimmy Morales. Honduras just underwent an outrageously corrupt election; in ensuing protests, scores of people have been killed by militarized security forces, many oppositionists have been jailed and people continue to flee the country.In Mexico, many suspect that, as has happened in the past, the right wing will rig the coming presidential election to keep the leftist front runner, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, from winning, and the country continues to be wracked by deadly violence. Paraguay has a similar situation to those of Guatemala and Honduras. In Peru, the president was just forced to resign because of a scandal in which he was credibly accused of pardoning former dictator Alberto Fujimori in exchange for immunity from impeachment under his own corruption charges.In Colombia, social justice activists are being murdered by death squads, and opposition leaders face state repression. In Guatemala, the indigenous population, a majority by some criteria, continues to be oppressed by the corrupt and undemocratic government of President Jimmy Morales. Honduras just underwent an outrageously corrupt election; in ensuing protests, scores of people have been killed by militarized security forces, many oppositionists have been jailed and people continue to flee the country.In Mexico, many suspect that, as has happened in the past, the right wing will rig the coming presidential election to keep the leftist front runner, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, from winning, and the country continues to be wracked by deadly violence. Paraguay has a similar situation to those of Guatemala and Honduras. In Peru, the president was just forced to resign because of a scandal in which he was credibly accused of pardoning former dictator Alberto Fujimori in exchange for immunity from impeachment under his own corruption charges.The oil multinationals and finance capital are also on the move in this drama, however. Former President Hugo Chávez had nationalized some properties of the most abusive multinationals, and they are maneuvering to get their property back if the current left-wing government of President Nicolás Maduro loses the Sunday elections.Most of the opposition parties in Venezuela, having failed to take power through violence, decided to boycott the elections and appeal to the United States and the “Lima Group” nations to intervene. However, three opposition presidential candidates did jump into the race: Henri Falcón, the former governor of Lara state until he was defeated by a leftist in last year’s gubernatorial elections, used to be a supporter of Chávez’s Bolivarian movement, but has now moved into opposition.He advocates neoliberal solutions for Venezuela’s economic crisis, such as partial dollarization and new approaches to the International Monetary Fund for help. He is probably the strongest of the opposition candidates in terms of support, but he has been denounced by others on the right for not joining the election boycott.Another opposition candidate is Javier Bertucci, an Evangelical Christian preacher. He preaches a return of Venezuela to Christian values, a stance that is somewhat undermined by his involvement in corruption scandals in recent years.The third opposition presidential candidate is another former supporter of the left-wing Bolivarian government, Reinaldo Quijada. He and his party, Popular and Political Unity, broke with the governing left-wing alliance (the Great Patriotic Pole) in 2015 and attacks the government of Maduro and his United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) from a far left position. He is supported by Venezuelan admirers of Leon Trotsky and others and could gain some votes from sectors of the Chavista base who want stronger pro-socialist measures.The Central Bank of Venezuela is responsible for developing monetary policy for the Venezuelan bolívar which is used as currency. The currency is primarily printed on paper and distributed throughout the country. The President of the Central Bank of Venezuela is presently Eudomar Tovar, who also serves as the country's representative in the International Monetary Fund. According to the Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal, Venezuela has the weakest property rights in the world, scoring only 5.0 on a scale of 100; expropriation without compensation is not uncommon. Venezuela has a mixed economy dominated by the petroleum sector, which accounts for roughly a third of GDP, around 80% of exports, and more than half of government revenues. Per capita GDP for 2009 was US$13,000, ranking 85th in the world. Venezuela has the least expensive petrol in the world because the consumer price of petrol is heavily subsidized.More than 60% of Venezuela's international reserves is in gold, eight times more than the average for the region. Most of Venezuela's gold held abroad is located in London. On November 25, 2011, the first of US$11 billion of repatriated gold bullion arrived in Caracas; Chávez called the repatriation of gold a "sovereign" step that will help protect the country's foreign reserves from the turmoil in the U.S. and Europe.[80] However government policies quickly spent down this returned gold and in 2013 the government was forced to add the dollar reserves of state owned companies to those of the national bank in order to reassure the international bond market.Manufacturing contributed 17% of GDP in 2006. Venezuela manufactures and exports heavy industry products such as steel, aluminium and cement, with production concentrated around Ciudad Guayana, near the Guri Dam, one of the largest in the world and the provider of about three-quarters of Venezuela's electricity. Other notable manufacturing includes electronics and automobiles, as well as beverages, and foodstuffs. Agriculture in Venezuela accounts for approximately 3% of GDP, 10% of the labor force, and at least a quarter of Venezuela's land area. Venezuela exports rice, corn, fish, tropical fruit, coffee, beef, and pork. The country is not self-sufficient in most areas of agriculture. In 2012, total food consumption was over 26 million metric tonnes, a 94.8% increase from 2003.Since the discovery of oil in the early 20th century, Venezuela has been one of the world's leading exporters of oil, and it is a founding member of OPEC. Previously an underdeveloped exporter of agricultural commodities such as coffee and cocoa, oil quickly came to dominate exports and government revenues. The 1980s oil glut led to an external debt crisis and a long-running economic crisis, which saw inflation peak at 100% in 1996 and poverty rates rise to 66% in 1995 as (by 1998) per capita GDP fell to the same level as 1963, down a third from its 1978 peak. The 1990s also saw Venezuela experience a major banking crisis in 1994. The recovery of oil prices after 2001 boosted the Venezuelan economy and facilitated social spending. In 2003 the government of Hugo Chávez implemented currency controls after capital flight lead to a devaluation of the currency. This lead to the development of a parallel market of dollars in the subsequent years with the official exchange rate less than a sixth of black market value. The fallout of the 2008 global financial crisis saw a renewed economic downturn.With social programs such as the Bolivarian Missions, Venezuela made progress in social development in 2000s, particularly in areas such as health, education, and poverty. Many of the social policies pursued by Chávez and his administration were jumpstarted by the Millennium Development Goals, eight goals that Venezuela and 188 other nations agreed to in September 2000.It is expected that Venezuela will meet all eight goals by the 2015 deadline.Industries: petroleum, construction materials, food processing, iron ore mining, steel, aluminum; motor vehicle assembly, real estate, tourism and ecotourism.

There comes a time in many people’s lives when they have to make a decision that will define them forever.Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has vowed to block the aid, calling it a pretext for US intervention in his crisis-stricken country. Venezuela is in the midst of a dire humanitarian crisis, and the relatively small amount of aid is meant to begin to relieve a severe shortage of basic goods that has fuelled malnutrition and disease. But opposition leaders and US officials also hope to elicit the first public mass defection of Venezuelan troops if the soldiers disavow their orders and accept the shipment.

There comes a time in many people’s lives when they have to make a decision that will define them forever.Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has vowed to block the aid, calling it a pretext for US intervention in his crisis-stricken country. Venezuela is in the midst of a dire humanitarian crisis, and the relatively small amount of aid is meant to begin to relieve a severe shortage of basic goods that has fuelled malnutrition and disease. But opposition leaders and US officials also hope to elicit the first public mass defection of Venezuelan troops if the soldiers disavow their orders and accept the shipment.