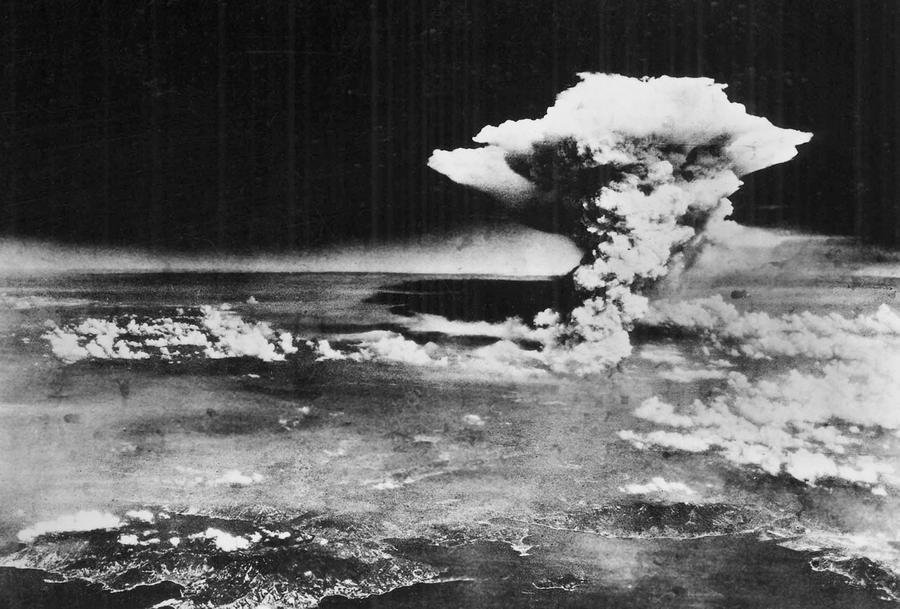

OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR II IN THE ASIA PACIFIC,THE FALL OF JAPANESE IMPERIAL AND JAPAN SURRENDERED .THE US DROPPED ATOMIC BOMBS IN HIROSHIMA & NAGASAKI IN AUGUST 1945 HAS LONG REMAINED ONE OF MOST CONTROVERSIAL DECISIONS OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR.

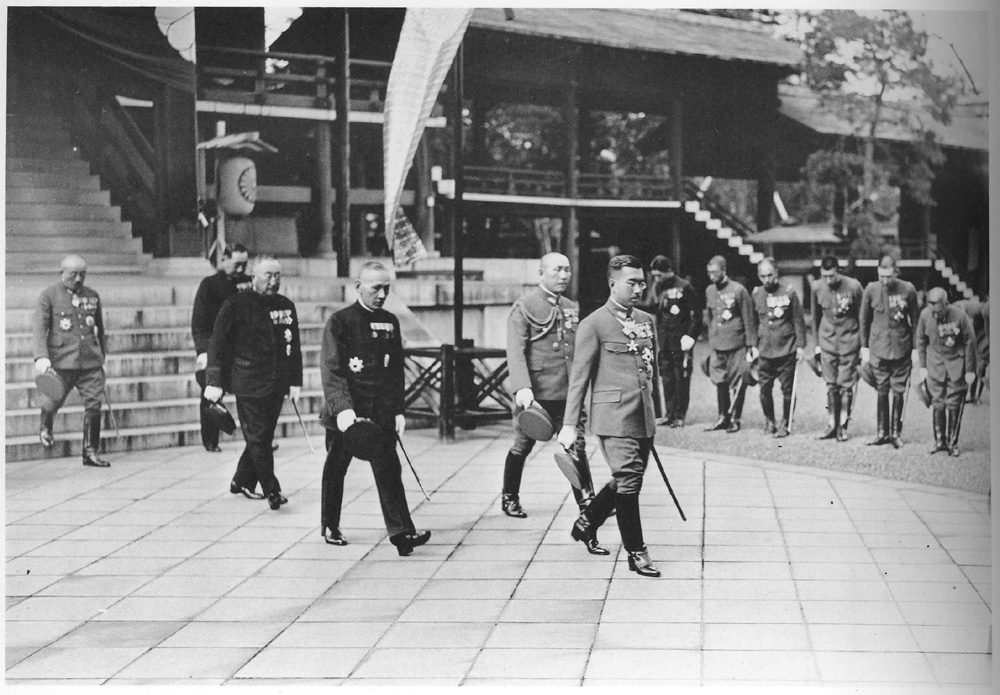

Hirohito quit Yasukuni Shrine visits over concerns about war criminals. Hirohito (1901 – 1989) was the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 25 December 1926, until his death. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Akihito. In Japan, he is now referred to primarily by his posthumous name, Emperor Shōwa The word Shōwa is the name of the era (Shōwa period , Shōwa jidai, potentially "period of enlightened peace/harmony" or "period of radiant Japan") that corresponded with the Emperor's reign, and was made the Emperor's own name upon his death.

Hirohito quit Yasukuni Shrine visits over concerns about war criminals. Hirohito (1901 – 1989) was the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 25 December 1926, until his death. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Akihito. In Japan, he is now referred to primarily by his posthumous name, Emperor Shōwa The word Shōwa is the name of the era (Shōwa period , Shōwa jidai, potentially "period of enlightened peace/harmony" or "period of radiant Japan") that corresponded with the Emperor's reign, and was made the Emperor's own name upon his death.

The primary foreign policy goal of Japan’s leadership in the 1870-1900 period was to rid Japan of the unequal treaties; both the government and public opinion objected to the treaties’ limitations on import duties and to the despised extraterritoriality. Thus, the newly nationalistic Meiji leadership undertook a host of reforms aimed at creating a Japanese state to them Japan needed to be unified and strong in the face of the outside threat. The government pursued a “rich country, strong army” policy: a modern, Western-style army, a new taxation system, conscription, a centralized local government structure, universal education, national universities, a European-style legal system, a Prussian-style constitution, built model factories to import up-to-date Western industrial technology, and encouraged entrepreneurship among rural landlords and the urban merchant class. Two reforms in this process of state building stand out: the creation of an orthodox nationalist ideology centered on the emperor reinvented tradition and the creation of a Japanese language.The ideology focused on the emperor as descended from the founding deities, as national father figure, and as the focus of the citizens’ loyalty. He became the symbol of Japanese nationalism.The newly created elementary school system was used as the primary disseminator of this patriotism. But in 1873, Japan did not have a unified language to spread nationalism. People spoke local dialects that were often mutually unintelligible, and the literate few wrote in a variety of difficult writing systems that were totally unlike the spoken language. Debates over how to reform the language raged throughout the late nineteenth century. Finally around 1900, the Education Ministry decided on a new language: elite Tokyo Japanese became kokugo, that is, “national language,” not “Japanese,” and the writing system was based on this new language. These two reforms, the creation of a new nationalist ideology and of a new national language allowed the government to turn “peasants into Japanese,” to borrow Eugen Weber’s title of his book on the same process in France in exactly the same time period.By the beginning of the twentieth century, these reforms were well underway. Japan had remade itself to the point that it was able to negotiate an end to the unequal treaties: Westerners in Japan came under Japanese law by the end of the century, and Japan finally regained tariff autonomy in 1913, over half a century after the limitations were imposed. But this did not end the Japanese quest for equality with the West. Even as Japan escaped its status as victim of imperialism, it joined in the European and American game—that is, Japan began to build its own empire, to be one of the perpetrators. The drive for empire can be better explained in nationalistic than economic terms: great nations have empires; if we are to be a great nation, we need an empire. In 1879 Japan annexed Okinawa. In 1894-5, Japan won a war with China and gained another colony, Taiwan; it also gained a huge indemnity from China and thus was able to take its monetary system onto the gold standard, a point of great national pride. Membership in these two clubs: the imperialist club and the gold standard club, reinforced Japan’s view of itself as a rising power.In 1902, Japan also made an alliance with Great Britain, another sign of its success—another Asian first: an alliance with the world’s primary power of the time. In 1904-5, Japan fought a war with Russia, and won once again. This brought Korea into Japan’s empire, and Manchuria into its economic sphere of influence. These annexations of territory, when viewed from today’s perspective, look like blatant aggression; however, they were well within the acceptable framework of Western imperialism. Britain, by signing its treaty with Japan in 1902, and then re-signing the pact after the war, endorsed the Japanese annexation of Korea. Theodore Roosevelt, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts, mediated the treaty that ended the war; the Treaty of Portsmouth signed in 1905 recognized Japan’s supremacy in Korea and thus the United States pre-approved Japan’s annexation of Korea (this was only seven years after the US had taken the Philippines from Spain and Hawaii from its ruling family, and three years after the United States military had brutally suppressed a Filipino independence movement.

The Imperial Japanese Army Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun; "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of War, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor of Japan as supreme commander of the army and the navy. Later an Inspectorate General of Aviation became the third agency with oversight of the army. During wartime or national emergencies, the nominal command functions of the emperor would be centralized in an Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ), an ad-hoc body consisting of the chief and vice chief of the Army General Staff, the Minister of War, the chief and vice chief of the Naval General Staff, the Inspector General of Aviation, and the Inspector General of Military Training.

The Imperial Japanese Army Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun; "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of War, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor of Japan as supreme commander of the army and the navy. Later an Inspectorate General of Aviation became the third agency with oversight of the army. During wartime or national emergencies, the nominal command functions of the emperor would be centralized in an Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ), an ad-hoc body consisting of the chief and vice chief of the Army General Staff, the Minister of War, the chief and vice chief of the Naval General Staff, the Inspector General of Aviation, and the Inspector General of Military Training.

Background Meiji Restoration of 1868 Japanese military rises in power Japanese Emperor becomes the symbolic icon of Japanese pride Historical and cultural legacies Highly valued the samurai code (bushido) .Weakness and surrender were seen as dishonourable.Japan’s ambitions, establish equality with the modern Western powers Create an empire similar to the Western empires Japan’s attitude towards war and international relations was shaped by how the different world powers interacted with Japan as it pursued these two aims.China Britain Russia America. Conflicts with China, Japan wanted to take advantage of China’s weaknesses and political instability Seized control of Taiwan and Korea from China in the First Sino-Japanese War. Issued the Twenty-One Demands in 1915 that forced China to give in to Japanese interests Encouraged Japan to expand further into China.Japan’s ambitions ,conflict with Russia , Russia wanted to establish military bases in Manchuria This threatened Japanese forces in Korea (see p.168) Japan wanted to negotiate a compromise but Russia refused! Japan declared war on Russia in 1905 and won! (Russo- Japanese War) .First time that an Asian power had beaten a Western power Gave Japan confidence that they could defeat the Western powers .On September 18, 1931, Japanese military officers planted a bomb on the Southern Manchurian railway and blamed the incident on Chinese soldiers. The Imperial Japanese Army used this fabricated incident as a n excuse for invading Manchuria, a move that historians designate as the start of the Asia - Pacific War. The area was turned into a Japanese puppet state called Manchukuo in 1932. The League of Nations condemned Japan for this aggression, and in response Japan withdrew from the League in 1933. A few years later, in 193 7 , Japan , Ger many and Italy formed the Axis Powers . On July 7 th, 1937 , Japan used a conflict between Chinese and Japanese troops around the Marco Polo Bridge at the outskirt of Beijing, as a pretext to launch an all - out but undeclared war against China, taking Shanghai and then Nanking (now called Nanjing) , China’s capital at the time. During a 6 to 8 - week period, Imperial soldiers reportedly killed tens of thousands of captured soldiers and civilians, a nd brutally treated and raped women and children . This massacre became known as the Rape of Nanking . Having occupied many parts of China, and with the war in Europe having broken out in 1939, Japan looked to the rest of Asia to secure an independent supply of natural resources. Japan thus continued imperial expansion in Asia under the guise of “liberating” Asia from Western domination, committing horrific atrocities and crimes against humanity along the way. These atrocities included mass slaughters, Japa nese military sexual slavery , the use of human experimentation in its biochemical warfare development, germ warfare attacks in China, the forced labor of POWs and civilians , and more. When the Imperial Japanese forces started moving into Indochina in 1940 - 1941, Western countries began to act . This included the US , the UK and Canada imposing economic sanctions against Japan. Japan thus decided that to win control over Asia, it would need to confront the United States. On December 7, 1 941, Imperial Japanese forces attacked US bases at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the Philippines. At the same time , Japanese forces also launched an assault against Commonwealth forces in Hong Kong and Malaya. The End of the War A rmed resistance to the Impe rial Japanese Army in China and other occupied countries , the US’s economic and technological superiority , and the joint efforts of the Allied Forces took its toll on Imperial Japan , putting it on the defensive by 1944. But the end of the war didn’t come until the summer of 1945, when the US , with the support of UK and Canada, dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. The first one fell on Hiroshima on August 6 and the second one on Nagasak i on August 9. This led to Imperial Japan officially surrendering on August 15, putting an end to 14 years of war in Asia.In December 1941 Japan, already at war with China, attacked British, Dutch and American territories in Asia and the Pacific. By June 1942, Japanese conquests encompassed a vast area of south-east Asia and the western Pacific. Under Japanese occupation,prisoners of war and enslaved civilians were forced to work for their captors in harsh and often inhuman conditions.A series of land battles were fought in China, Burma and New Guinea. Although Japan achieved early successes, its resources were overstretched. In contrast, America was able to mobilise huge economic resources to intensify its efforts, beginning with amphibious landings in the Pacific. Tokyo and other Japanese cities suffered unprecedented destruction by conventional bombing. Finally, after atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and following Soviet intervention, Japan surrendered in August 1945.Japanese occupation hastened the end of European colonialism and the rise of communism in Asia, while post-war American occupation transformed Japanese society.The conflict continued during World War I this time over Japanese policy toward China. One group advocated a more autonomous Japanese policy from Great Britain and the United States on the Asian mainland. Japan should use loans to competing Chinese warlords and military intervention to gain what it saw as its deserved imperialist position in China. The Twenty-One Demands of 1915, the Japanese government’s attempt, in the absence of an Anglo-American presence during World War I, to become the primary imperialist power in China, and the Nishihara Loans of 1917-18, represented this view. Takahashi and others opposed this approach on three grounds: it alienated the Chinese government, with whom Japan should cooperate economically; it aroused Chinese nationalism, which he feared would rebound against Japan in the future; and it endangered Japan’s relations with Britain and America. In 1920, Takahashi, while serving as finance minister, not only criticized his government’s China policy, but even advocated the abolition of the army’s and navy’s general staffs because they undermined the democratizing government’s control over foreign policy. In 1923, he called for the appointment of civilian army and navy ministers. As the dean of historians of Taisho democracy, Shinobu Seizaburo wrote, “Takahashi was the leading representative of the bourgeois politicians who advocated civilian control of the military.” His China policy views won out temporarily, but efforts to control the military did not. Moreover, in the process he made powerful enemies; his inflammatory memorandum was leaked to the army, which produced over 500 pages of critical responses.

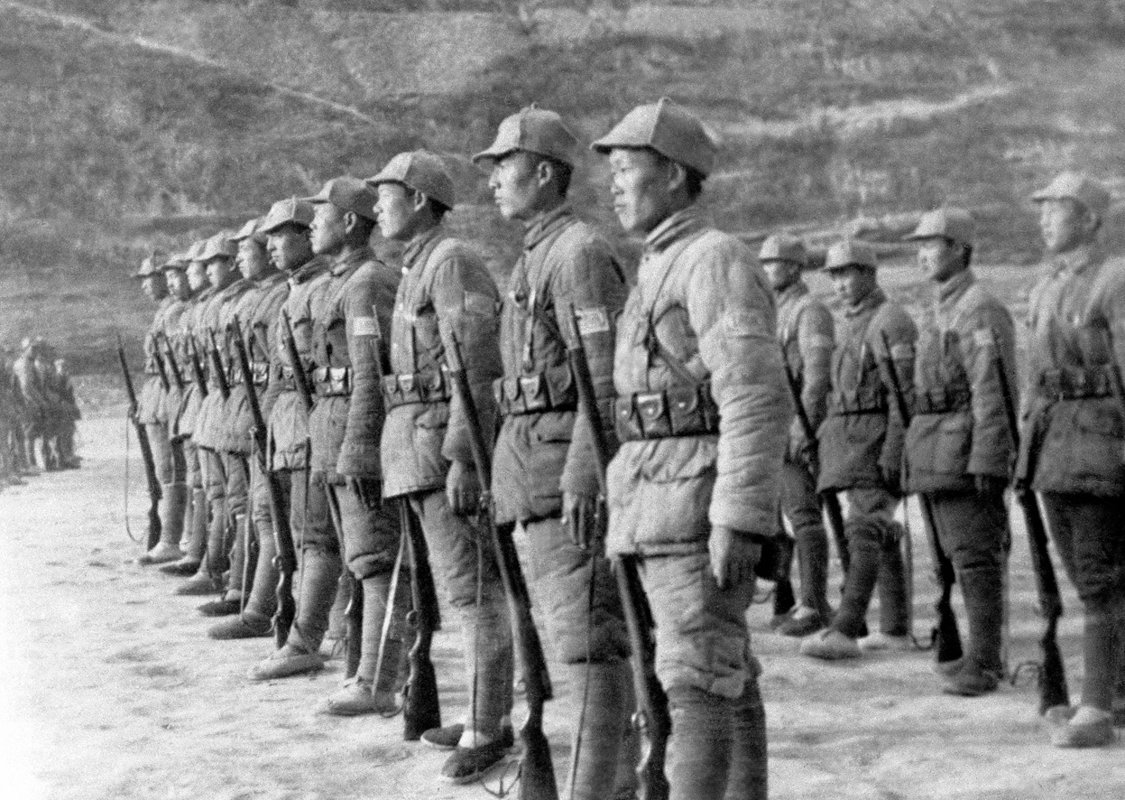

Entering their fourth year of war against Japan, Chinese military forces were strengthening their air force, producing their own armaments, and training their officers in the methods of modern war. Here, Chinese cadets in full battle dress, they favor the German type of steel helmet, on parade somewhere in China, on July 11, 1940.

Entering their fourth year of war against Japan, Chinese military forces were strengthening their air force, producing their own armaments, and training their officers in the methods of modern war. Here, Chinese cadets in full battle dress, they favor the German type of steel helmet, on parade somewhere in China, on July 11, 1940.

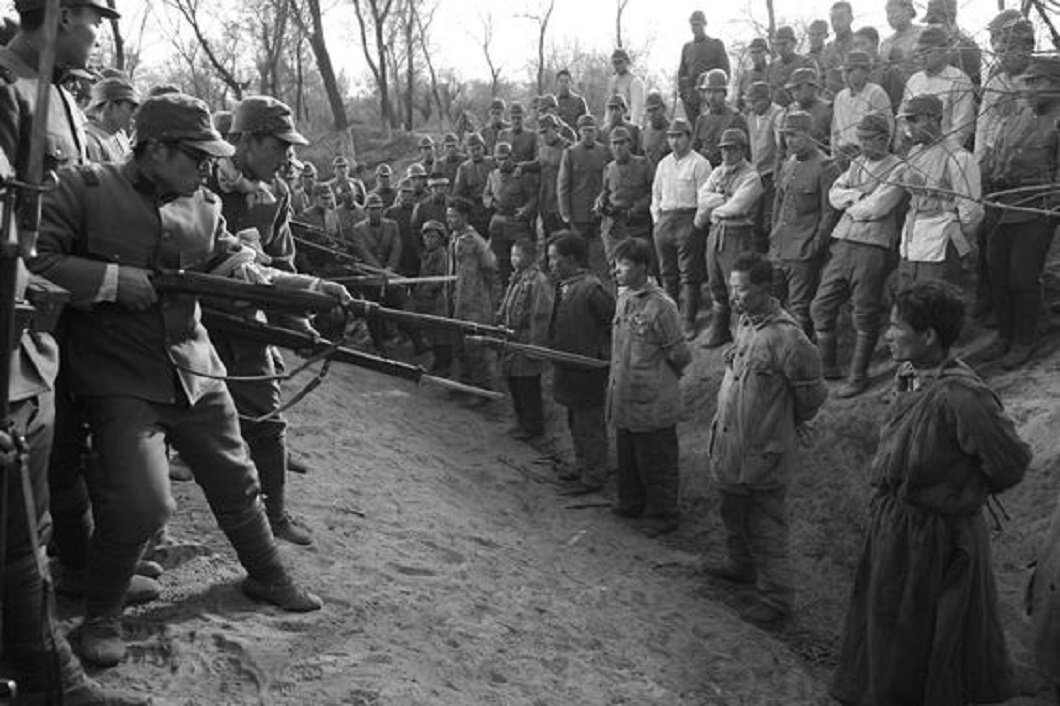

Rape of Nanking,the Nanking Massacre was an episode of mass murder and mass rape committed by Japanese troops against the residents of Nanjing (Nanking), then the capital of the Republic of China, during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The massacre is also known as the Rape of Nanking or, using Pinyin romanization, the Nanjing Massacre or Rape of Nanjing.The massacre occurred over a period of six weeks starting on December 13, 1937, the day that the Japanese captured Nanjing. During this period, soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army murdered Chinese civilians and disarmed combatants who numbered an estimated 40,000 to over 300,000, and perpetrated widespread rape and looting.

Rape of Nanking,the Nanking Massacre was an episode of mass murder and mass rape committed by Japanese troops against the residents of Nanjing (Nanking), then the capital of the Republic of China, during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The massacre is also known as the Rape of Nanking or, using Pinyin romanization, the Nanjing Massacre or Rape of Nanjing.The massacre occurred over a period of six weeks starting on December 13, 1937, the day that the Japanese captured Nanjing. During this period, soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army murdered Chinese civilians and disarmed combatants who numbered an estimated 40,000 to over 300,000, and perpetrated widespread rape and looting.

Soviet entry into the war was indeed a shock to the Japanese ruling elite, both civilian and military alike. Politically and diplomatically, it dashed any hope of ending the war through Soviet mediation. But Soviet entry meant more than merely precluding the option of Soviet mediation for peace. Here, we must consider the political calculations and psychological factors apparent in dealing with Japan’s two enemies. Before the invasion of Manchuria, the Soviet Union had been Japan’s best hope for peace, while the Japanese ruling elite felt bitter resentment toward the United States, which had demanded unconditional surrender. After August 9, this relationship was reversed. The small opening that the United States had intentionally left ajar in the Potsdam terms, which Japanese foreign ministry officials had astutely noticed as soon as the Potsdam Proclamation was issued, suddenly looked inviting, providing the only room in which the Japanese could maneuver. They concluded that suing for peace with the United States would confer a better chance of preserving the imperial house, if not the kokutai as it was envisaged by ultranationalists. No sooner had the marriage of convenience uniting right-wing Japan and the communist Soviet Union broken down than the Japanese ruling elite’s fear of communism sweeping away the emperor system was reawakened. To preserve the imperial house, it would be better to surrender before the USSR was able to dictate terms. On August 13, rejecting Anami’s request that the decision to accept U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes’s counteroffer (the “Byrnes note”), which rejected Japan’s conditional acceptance of the Potsdal terms, be postponed, Suzuki explained: “If we miss today, the Soviet Union would take not only Manchuria, Korea, [and] Karafuto [Sakhalin Island], but also Hokkaido. This would destroy the foundation of Japan. We must end the war when we can deal with the United States.”[68] Furthermore, when Shigemitsu had a crucial meeting with Kido on the afternoon of August 9 at Prince Konoe’s request, which eventually led to Kido’s meeting with Hirohito that persuaded the emperor to accept the “sacred decision” scenario, Shigemitsu stressed the negative effect of further Soviet expansion on the fate of the imperial household.What motivated Hirohito was neither a pious wish to bring peace to humanity nor a sincere desire to save the people and the nation from destruction, as his imperial rescript stated and as the myth of the emperor’s “sacred decision” would have us believe. More than anything else, it was a sense of personal survival and deep responsibility to maintain the imperial house, which had lasted in unbroken lineage since the legendary Jinmu emperor. For that purpose, Hirohiro was quick to jettison the pseudo-religious concept of the kokutai, and even the emperor’s prerogatives as embodied in the Meiji Constitution. What mattered to him was the preservation of the imperial house, and to that end, he was willing to entrust his fate to the will of the Japanese people. Hirohito’s transformation from a living god (arahitogami) to a human emperor (ningen tenno), which is seen as having occurred during the American occupation, actually took place during the final “sacred decision” at the imperial conference. With astonishing swiftness, the members of the imperial house closed ranks and defended Hirohito’s decision. To attain this objective, Hirohito was prepared to part with the military and the ultranationalists, who were major obstacles.It is difficult to document just how the Soviet factor influenced the emperor’s decision and the thinking of his close advisers. It is possible to conjecture, however, that the emperor and his advisers wished to avoid any Soviet influence in determining the fate of the imperial household and the emperor’s status. It is not far-fetched to assume that Suzuki’s statement and Shigemitsu’s thinking quoted above, which explain the need to accept the Byrnes note before the Soviet Union expanded its conquered territories, was widely shared by the ruling circles in Japan.There was another factor in the political calculations of the Japanese ruling elite: fear of popular unrest. On August 12, Navy Minister Yonai Mitsumasa told Takagi Sokichi: “They may not be the appropriate words, but the atomic bombs and the Soviet entry into the war are in a way a godsend, since we don’t have to decide to stop the war because of the domestic situation. The reason why I have advocated the end of war is not that I was afraid of the enemy’s attack, nor was it because of the atomic bombs or the Soviet entry into the war. It was more than anything else because I was afraid of domestic conditions. Therefore, we were fortunate to [be able to] end the war without pushing the domestic situation to the fore.”Yonai’s fear was widely shared by the ruling elite. Konoe’s advocacy of peace, which he had submitted to Hirohito in February 1945, was motivated by his fear of a communist revolution. Whether or not such a revolution was actually likely or even possible, the fear among the ruling elite of such popular unrest sweeping away the entire emperor system was quite real. On August 13, 14, and 15, Kido met Machimura Kingo, chief of the Metropolitan Police, to hear reports of possible political and social turmoil at home.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 pitted expansionist Russia against up-and-coming Japan. Russia sought warm-water ports and control of Manchuria, while Japan opposed them. Japan emerged as a naval power and Admiral Togo Heihachiro achieved international fame. Russia lost two of its three naval fleets.The Japanese Empire defeated the Russian Empire, t. It was a negotiated peace, rather than a complete or crushing victory, but hugely important for Japan's rising status in the world.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 pitted expansionist Russia against up-and-coming Japan. Russia sought warm-water ports and control of Manchuria, while Japan opposed them. Japan emerged as a naval power and Admiral Togo Heihachiro achieved international fame. Russia lost two of its three naval fleets.The Japanese Empire defeated the Russian Empire, t. It was a negotiated peace, rather than a complete or crushing victory, but hugely important for Japan's rising status in the world.

After Germany surrendered in May of 1945, Allied attention focused on Japan. The island-hopping strategy adopted by the U.S. Navy successfully brought B-29 bombers within range of Japan's Home Islands, and they carried out massive attacks involving high explosives, incendiary bombs, and finally the two most powerful weapons ever used in war: the newly-invented atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In June, after more than 80 days of fighting, Allied forces captured the Japanese island of Okinawa, but at a horrible cost, with more than 150,000 casualties on both sides, and tens of thousands of civilians dead (many by their own hand). Okinawa was seen as a painful preview of a planned full invasion of Japan, and Allied generals predicted massive casualties if it took place. As the U.S. carried out the atomic bombings, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, invading occupied Manchuria with a force of more than one million soldiers and, quickly defeating Japan's Kwantung Army. Six days after the bombing of Nagasaki, and after much internal struggle, Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945. World War II was over. Next week, in the final entry in this series, we'll take a look at what came next in the new post-war era.On Monday, August 6, 1945, a mushroom cloud billows into the sky about one hour after an atomic bomb was dropped by American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, detonating above Hiroshima, Japan. Nearly 80,000 people are believed to have been killed immediately, with possibly another 60,000 survivors dying of injuries and radiation exposure by 1950.What Truman did not know, and which has only been established quite recently, is that the Imperial Japanese Army could never contemplate surrender, having forced all their men to fight to the death since the start of the war. All civilians were to be mobilised and forced to fight with bamboo spears and satchel charges to act as suicide bombers against Allied tanks. Japanese documents apparently indicate their army was prepared to accept up to 28 million civilian deaths.The dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was justified at the time as being moral – in order to bring about a more rapid victory and prevent the deaths of more Americans. However, it was clearly not moral to use this weapon knowing that it would kill civilians and destroy the urban milieu. And it wasn’t necessary either.Militarily Japan was finished (as the Soviet invasion of Manchuria that August showed). Further blockade and urban destruction would have produced a surrender in August or September at the latest, without the need for the costly anticipated invasion or the atomic bomb. As for the second bomb on Nagasaki, that was just as unnecessary as the first one. It was deemed to be needed, partly because it was a different design, and the military (and many civilian scientists) were keen to see if they both worked the same way. There was, in other words, a cynical scientific imperative at work as well.I should also add that there was a fine line between the atomic bomb and conventional bombing – indeed descriptions of Hamburg or Tokyo after conventional bombing echo the aftermath of Hiroshima. To regard Hiroshima as a moral violation is also to condemn the firebombing campaign, which was deliberately aimed at city centres and completely indiscriminate.The first Americans to reach Hiroshima and Nagasaki - servicemen, scientists and journalists - described in great detail the apocalyptic scenes they encountered. They saw a grey, blasted landscape, in which thousands of hideously burnt people were huddled in shanties, coughing up and urinating blood, with their hair falling out in clumps, waiting to die.The writer and journalist John Hersey, one of the first to get to Hiroshima, wrote a powerful study of the plight of six of these survivors, and this was published in the New Yorker in 1946. Suddenly the talk of New York’s literati, Hersey followed this up with a monograph, Hiroshima, published the following year, which was immediately a best-seller, and was translated into Japanese three years later.At the same time as Hersey’s article, the United States Army Air Force published a survey of the effects of strategic bombing on Japan. The Air Force argued that conventional B-29 attacks had all but brought Japan to its knees, and concluded, Not to be outdone, the United States Navy produced its own assessment, stating that its submarine campaign had also brought Japan to its knees, that the Home Islands were on the verge of starvation, and that this alone would have produced surrender, thereby obviating the need for an atomic bomb, or an invasion.And then the State Department added its assessment. Joseph Grew - America’s last ambassador to Japan before the war started - claimed that Japanese diplomats had been trying to open surrender negotiations with the United States via the then still neutral Soviet Union. These were overtures that the Truman administration knew about, thanks to decrypts of Japanese diplomatic codes, but which they nevertheless chose to ignore. Grew added that if the United States had modified the demand for unconditional surrender, made on 26 July at Potsdam, if it had simply guaranteed the continuation of the imperial system in Japan, the Japanese would almost certainly have capitulated within days.

America's use of atomic bombs to attack the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 has long remained one of the most controversial decisions of the Second World War.On Monday, August 6, 1945, a mushroom cloud billows into the sky about one hour after an atomic bomb was dropped by American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, detonating above Hiroshima, Japan. Nearly 80,000 people are believed to have been killed immediately, with possibly another 60,000 survivors dying of injuries and radiation exposure by 1950.

America's use of atomic bombs to attack the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 has long remained one of the most controversial decisions of the Second World War.On Monday, August 6, 1945, a mushroom cloud billows into the sky about one hour after an atomic bomb was dropped by American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, detonating above Hiroshima, Japan. Nearly 80,000 people are believed to have been killed immediately, with possibly another 60,000 survivors dying of injuries and radiation exposure by 1950.

Another theory differs slightly from the traditionalist narrative. Some scholars still see the bomb as decisive. But they see it as an excuse for the Japanese leadership to end the war without facing an internal challenge. Herbert P. Bix, whose award-winning biography of Hirohito focused on internal Japanese records, contends that in 1945 many Japanese leaders were in a state of paranoia about a possible internal uprising. Especially after the government’s strictures against surrender, the emperor and his Cabinet worried about the consequences of capitulating. They were especially afraid of leftists or communist agitation. Despite the country’s strong nationalism, the 1940s had produced some general discontent because of rationing, bombings, and other wartime exigencies.Bix argues that the emperor and the Cabinet saved face by declaring that they were surrendering in order to prevent further atomic bombings. This explanation helps to rationalize an apparent contradiction between the emphasis on saving Japanese lives in Hirohito’s radio broadcast and the government’s previously cavalier attitude toward their own civilian population. In the months before surrender, the Japanese government had ramped up the amount of kamikaze attacks. Just days before the final decision, they had been arming citizens with bamboo sticks to fend off a land invasion.Bix posits that the bombs’ impact was not that they shocked the Japanese into giving up (he agrees with Hasegawa on this point), but that they allowed for the completion of a surrender process that was already desired. As with other theories above, this argument relies on guessing the thought process of the Japanese leaders.Fearing a military coup to ensure continuation of the war, the Emperor decided to take additional action to bring the conflict to an end. On 13 August, when the Cabinet was called into immediate session, members Anami Korechika, Umezo Yoshijir, and Toyoda Soemu unexpectedly dissented anew, saying that an item in the original Potsdam proposal stipulating that postwar Japan would ultimately be governed by the will of the people was against Japanese tradition and therefore compliance was impossible. This reversal precipitated another Imperial Conference at which the Emperor stopped all argument by forcefully declaring that Japan would accept the Potsdam conditions as modified in the 11 August message from US Secretary of State Byrnes on behalf of the Allied nations.In an action without precedent, the Emperor decided to issue an Imperial Rescript announcing the capitulation, to be delivered both to the Allies through diplomatic channels and to his subjects in his own voice via radio broadcast. The enormity of this decision must be understood in context: the Emperor was considered a deity—no one was allowed to look upon him from above, few citizens had seen him at all, and the Japanese people had never before heard his voice. Hirohito well understood the powerful effect his broadcast would have.On 14 August, the Emperor made two recordings of the Rescript for broadcast the next day. Aware that such a powerful communication would doom efforts to continue the war, the military sent soldiers from a Tokyo garrison to attack the Imperial Palace at night, imprison the Emperor, and seize the recordings. They failed to turn up the recordings, however, which had been secured at the radio station. Later that night, War Minister Anami Korechika, having failed to promote his views and control his soldiers, committed suicide, the first of many such actions in the days that followed.Japanese World War II leader Hideki Tojo wanted to keep fighting even after U.S. atomic bombs destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, accusing surrender proponents of being "frightened," a newly released diary reveals.Excerpts from the approximately 20 pages written by Tojo in the final days of the war and held by the National Archives of Japan were published for the first time in several newspapers."The notes show Tojo kept his dyed-in-the-wool militarist mentality until the very end," said Kazufumi Takayama, the archives curator, who confirmed the accuracy of the published excerpts. "They are extremely valuable."Tojo, executed in 1948 after being convicted of war crimes by the Allies, was prime minister during much of the war. The notes buttress other evidence that Tojo was fiercely opposed to surrender despite the hopelessness of Japan's war effort."We now have to see our country surrender to the enemy without demonstrating our power up to 120 percent," Tojo wrote on Aug. 13, 1945, just two days before Japan gave up. "We are now on a course for a humiliating peace, or rather a humiliating surrender."Tojo also criticized his colleagues, accusing government leaders of "being scared of enemy threats and easily throwing their hands up." Surrender proponents were "frightened by 'the new type of bomb' and terrified by the Soviet Union's entry into the war," he wrote.

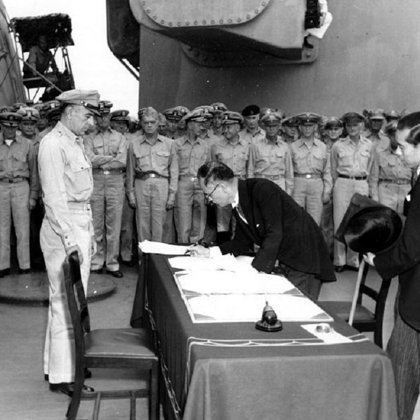

The scene aboard the battleship Missouri as the Japanese surrender documents were signed in Tokyo Bay, on September 2, 1945. Here, General Yoshijiro Umezu signs the Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Armed Forces of Japan, Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu (behind him, in top hat) had earlier signed on behalf of the government. Both men were later tried and convicted of war crimes. Umezu died while in prison, Shigemitsu was paroled in 1950, and served in the Japanese government until his death in 1957.

The scene aboard the battleship Missouri as the Japanese surrender documents were signed in Tokyo Bay, on September 2, 1945. Here, General Yoshijiro Umezu signs the Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Armed Forces of Japan, Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu (behind him, in top hat) had earlier signed on behalf of the government. Both men were later tried and convicted of war crimes. Umezu died while in prison, Shigemitsu was paroled in 1950, and served in the Japanese government until his death in 1957.