THE AFRICAN SLAVE TRADE (1440-1640).WHETHER SLAVERY EXISTED WITHIN SUB - SAHARAN AFRICAN SOCIETIES BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS .PEOPLE WERE SHIPPED TO SOUTH AMERICA AND THE SOUTH - EAST COAST OF WHAT TODAY THE UNITED STATES ,AND THE CARIBBEAN.

Portugal had a monopoly on the export of slaves from Africa. It is notable that they were also the last European country to abolish the institution -The most significant routes of the slave ships led from the north-western and western coasts of Africa to South America and the south-east coast of what is today the United States, and the Caribbean. As many as 20 million Africans were transported by ship. At the beginning of the African slave period, many slaves came from Sudan (present Liberia, Nigeria, Dahomey, and the Gold Coast); the Bantu (present Angola, Mozambique and Zaire); and the Islamic African countries.These three main places are the roots of African slaves and their culture

Portugal had a monopoly on the export of slaves from Africa. It is notable that they were also the last European country to abolish the institution -The most significant routes of the slave ships led from the north-western and western coasts of Africa to South America and the south-east coast of what is today the United States, and the Caribbean. As many as 20 million Africans were transported by ship. At the beginning of the African slave period, many slaves came from Sudan (present Liberia, Nigeria, Dahomey, and the Gold Coast); the Bantu (present Angola, Mozambique and Zaire); and the Islamic African countries.These three main places are the roots of African slaves and their cultureWhen the first Europeans arrived in the late fifteenth century, many inhabitants of the Gold Coast area were striving to consolidate their newly acquired territories and to settle into a secure and permanent environment. Several immigrant groups had yet to establish firm ascendancy over earlier occupants of their territories, and considerable displacement and secondary migrations were in progress. Ivor Wilks, a leading historian of Ghana, observed that Akan purchases of slaves from Portuguese traders operating from the Congo region augmented the labor needed for the state formation that was characteristic of this period. Unlike the Akan groups of the interior, the major coastal groups, such as the Fante, Ewe, and Ga, were for the most part settled in their homelands.The Portuguese were the first to arrive. By 1471, under the patronage of Prince Henry the Navigator, they had reached the area that was to become known as the Gold Coast because Europeans knew the area as the source of gold that reached Muslim North Africa by way of trade routes across the Sahara. The initial Portuguese interest in trading for gold, ivory, and pepper so increased that in 1482 the Portuguese built their first permanent trading post on the western coast of present-day Ghana. This fortress, Elmina Castle, constructed to protect Portuguese trade from European competitors and hostile Africans, still stands.With the opening of European plantations in the New World during the 1500s, which suddenly expanded the demand for slaves in the Americas, trade in slaves soon overshadowed gold as the principal export of the area. Indeed, the west coast of Africa became the principal source of slaves for the New World. The seemingly insatiable market and the substantial profits to be gained from the slave trade attracted adventurers from all over Europe. Much of the conflict that arose among European groups on the coast and among competing African kingdoms was the result of rivalry for control of this trade.The Portuguese position on the Gold Coast remained secure for almost a century. During that time, Lisbon leased the right to establish trading posts to individuals or companies that sought to align themselves with the local chiefs and to exchange trade goods both for rights to conduct commerce and for slaves whom the chiefs could provide. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, adventurers--first Dutch, and later English, Danish, and Swedish were granted licenses by their governments to trade overseas. On the Gold Coast, these European competitors built fortified trading stations and challenged the Portuguese. Sometimes they were also drawn into conflicts with local inhabitants as Europeans developed commercial alliances with local chiefs.The principal early struggle was between the Dutch and the Portuguese. With the loss of Elmina in 1642 to the Dutch, the Portuguese left the Gold Coast permanently. The next 150 years saw kaleidoscopic change and uncertainty, marked by local conflicts and diplomatic maneuvers, during which various European powers struggled to establish or to maintain a position of dominance in the profitable trade of the Gold Coast littoral. Forts were built, abandoned, attacked, captured, sold, and exchanged, and many sites were selected at one time or another for fortified positions by contending European nations.

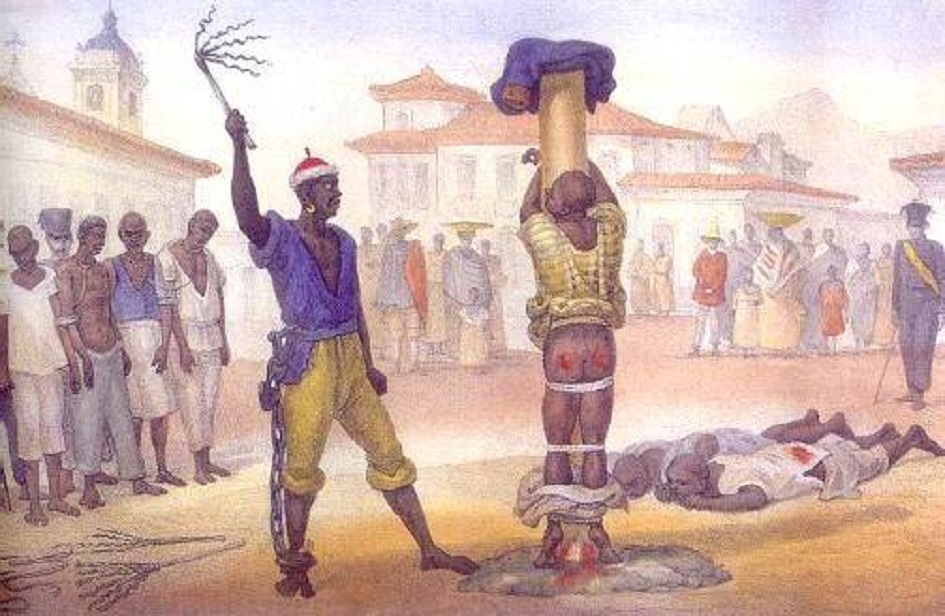

Both the Dutch and the British formed companies to advance their African ventures and to protect their coastal establishments. The Dutch West India Company operated throughout most of the eighteenth century. The British African Company of Merchants, founded in 1750, was the successor to several earlier organizations of this type. These enterprises built and manned new installations as the companies pursued their trading activities and defended their respective jurisdictions with varying degrees of government backing. There were short-lived ventures by the Swedes and the Prussians. The Danes remained until 1850, when they withdrew from the Gold Coast. The British gained possession of all Dutch coastal forts by the last quarter of the nineteenth century, thus making them the dominant European power on the Gold Coast. The exploitation of a pre-existing slave market in Africa was far from being able to implement the huge market of the Americas which required millions of laborers. Since slaves were obtained mainly through wars, the only reliable solution to this problem was to generate permanent warfare between and within nations. From Senegal to Angola and Mozambique, African rulers were methodically played against each other by the European companies: the French Company of the West Indies, the British Royal African Company, and the Dutch India Company among others. The European businessmen also soon understood that war was not enough by itself. Putting the African elites in the middle of an enslaving business would prove to be more efficient. Addiction to European commodities was the bait used in their strategy in which alcohol and firearms played a key role. Wine and hard liquor were used in negotiations in order to obtain the best terms of trade and ultimately became basic items of the same trade. Firearms were highly demanded in the process of empire building. They turned the traditionally peaceful successions into civil wars in which the European companies supported the candidates whom they later used as indispensable allies for the slave trade. In time of peace, farmers were kidnapped in their fields by mercenaries, usually royal slaves (jaami Buur in Wolof), linked to local elites and armed by European companies. Villages were raided at night, just before daybreak, when bodies were totally numbed by the last hours of sleep. Dwellings were set on fire to increase confusion. Elderly people, and sometime children, were exterminated and their bodies left to rot under the sun, becoming prey to vultures and hyenas. The strong ones were caught, shackled, and walked to the coast, carrying trade goods such as elephant tusks on their heads. Many died of exhaustion on their way to the coast or from starvation while awaiting slave ships. Many others died during the middle passage or shortly after their arrival. To this very day, Wolof griots still sing this song of sorrow which clearly depicts the reign of tyranny during slavery time.

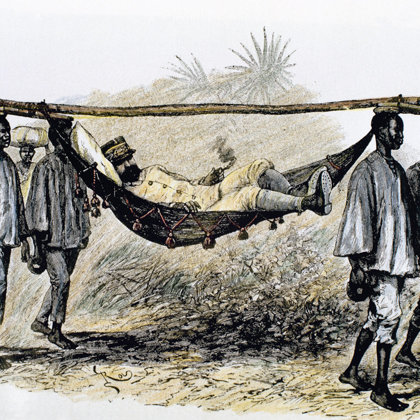

Expanding European empires in the New World lacked one major resource a workforce. In most cases, the indigenous peoples had proved unreliable (most of them were dying from diseases brought over from Europe), and Europeans were unsuited to the climate and suffered under tropical diseases. Africans, on the other hand, were excellent workers: they often had experience of agriculture and keeping cattle, they were used to a tropical climate, resistant to tropical diseases, and they could be "worked very hard" on plantations or in mines.

Expanding European empires in the New World lacked one major resource a workforce. In most cases, the indigenous peoples had proved unreliable (most of them were dying from diseases brought over from Europe), and Europeans were unsuited to the climate and suffered under tropical diseases. Africans, on the other hand, were excellent workers: they often had experience of agriculture and keeping cattle, they were used to a tropical climate, resistant to tropical diseases, and they could be "worked very hard" on plantations or in mines.

During the heyday of early European competition, slavery was an accepted social institution, and the slave trade overshadowed all other commercial activities on the West African coast. To be sure, slavery and slave trading were already firmly entrenched in many African societies before their contact with Europe. In most situations, men as well as women captured in local warfare became slaves. In general, however, slaves in African communities were often treated as junior members of the society with specific rights, and many were ultimately absorbed into their masters' families as full members. Given traditional methods of agricultural production in Africa, slavery in Africa was quite different from that which existed in the commercial plantation environments of the New World.Another aspect of the impact of the trans-Atlantic slave trade on Africa concerns the role of African chiefs, Muslim traders, and merchant princes in the trade. Although there is no doubt that local rulers in West Africa engaged in slaving and received certain advantages from it, some scholars have challenged the premise that traditional chiefs in the vicinity of the Gold Coast engaged in wars of expansion for the sole purpose of acquiring slaves for the export market. In the case of Asante, for example, rulers of that kingdom are known to have supplied slaves to both Muslim traders in the north and to Europeans on the coast. Even so, the Asante waged war for purposes other than simply to secure slaves. They also fought to pacify territories that in theory were under Asante control, to exact tribute payments from subordinate kingdoms, and to secure access to trade routes--particularly those that connected the interior with the coast. It is important to mention, however, that the supply of slaves to the Gold Coast was entirely in African hands. Although powerful traditional chiefs, such as the rulers of Asante, Fante, and Ahanta, were known to have engaged in the slave trade, individual African merchants such as John Kabes, John Konny, Thomas Ewusi, and a broker known only as Noi commanded large bands of armed men, many of them slaves, and engaged in various forms of commercial activities with the Europeans on the coast.The discovery of the New World boosted the European economy and marked the starting point of what one can call the "African nightmare.” The exploitation of the new land required millions of skilled laborers capable of standing the tropical climate which encompasses the vast region from the US South down to Brazil. The enslavement of Indians rapidly proved to be inefficient because the native population was hard to control and it was profoundly affected by the diseases brought from the Old world. The solution to the need of labor was the forced transportation to the colonies of poverty-stricken people, euphemistically called "indentured servants" or "engagés" in French. Europeans could not obviously count on their own "proletarians" who did not have the suited skills especially when tropical agriculture was concerned. The final solution came from Africa where Europeans discovered a potential slave market at the time of their arrival in the middle of the fifteenth century.Slaves were only a byproduct of the African market before the European colonization of the Americas. The Portuguese, who came first, were primarily interested in the gold which was hitherto brought to Europe by the trans-Saharan trade handled by the Arabo-Berbers. Their goal was also to connect directly with the Asian market of silk and spices from which Europe was barred with the rise of the Ottoman Empire which controlled the Eastern Mediterranean sea.The Portuguese were soon followed by the Dutch, the Danes, the French, the English, the Brandburgers (Germans), the Spaniards and other nations who completed the "encirclement" of Africa which led later to its effective colonization. The Portuguese first saw the coast of Senegambia in 1444. By the end of the century they had already set the curve to Asia when they discovered the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. This was also the time when Christopher Columbus made the "discovery" which changed the course of history. So far slaves were being transported in small numbers to Portugal, Spain, as well as the Atlantic islands. Most of them were kidnapped on the coast of Northern Senegambia, notably in Wolof and Berber villages, and put to work on the Iberian islands where the Moors had previously developed rice and sugar cane plantations, using African and European slaves. When the Reconquista expelled the Moors from the Iberian Peninsula in the second half of the 15th century, the demand for skilled laborers rose sharply. This demand then peaked with the colonization of the Americas. Africa could not satisfy it since the slave market was too narrow. People were being enslaved in this continent through warfare and put to work for reparations if their kins failed to liberate them through exchange of prisoners or buying them out. Others were enslaved to pay their debts or for committing crimes such as adultery or murder. In the Sahel and Savannah lands north of the equator, the captives (called jaam sayor by the Wolof) supplemented the trans-Saharan trade which lasted many centuries before and after the arrival of the Europeans. But the crossing of the Saharan desert, exclusively handled with camel caravans, prevented the transportation of large numbers of slaves.

The overwhelming majority of slaves sold to Europeans had not been slaves in Africa. They were free people who were captured in war or were victims of banditry or were enslaved as punishment for certain crimes. In Senegambia, the Guinea Coast, and the Slave Coasts of West Africa, war was the most important source of slaves. In Angola, kidnapping and condemnation for debt were very important. In most cases, rulers or merchants were not selling their own subjects, but people they regarded as alien. We must remember that Africans did not think of themselves as Africans, but as members of separate nations.

The overwhelming majority of slaves sold to Europeans had not been slaves in Africa. They were free people who were captured in war or were victims of banditry or were enslaved as punishment for certain crimes. In Senegambia, the Guinea Coast, and the Slave Coasts of West Africa, war was the most important source of slaves. In Angola, kidnapping and condemnation for debt were very important. In most cases, rulers or merchants were not selling their own subjects, but people they regarded as alien. We must remember that Africans did not think of themselves as Africans, but as members of separate nations.

African slavery arose long before Europeans came to the region, probably as early as 1550 BC in Northern Africa. The ancient Egyptians used Hebrews, Babylonians and other war captives to work as slaves to work in the Pharaoh's palace and the houses of nobility.In West Africa, we know about slavery from about 900 AD. But the lives of African slaves in WestAfrica and African American slaves were very different. In many West African societies, land was owned by communities, not by individuals. Social status and class could therefore not be based on land ownership. Instead, they were based on one's place in the social environment. Slaves were thus part of the family as well as private property. And slavery was not a lifetime status,someone might be born free, made a slave for a few years, and then be free again for the rest of their life.Slaves also had rights; they could marry, own property, and inherit substantial goods from their owner. They could even own slaves themselves. Their children were generally born into freedom, not servitude. Some owners even adopted their slaves as family.When Europeans first came to Africa in search of slaves, the African leaders themselves were eager to contribute. Initially, the slaves were war prisoners, criminals or people in debt. However, as the European demand for slaves grew, African leaders turned to new ways to find slaves. Wars were started for the sole reasons of taking prisoners to sell, and many were simply kidnapped (either by people from their own tribe, or from competing tribes). Some African rulers earned great profits by controlling the regional slave trade.Slavery in Africa has not only existed throughout the continent for many centuries, but continues in the current day. Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of the continent, as they were in much of the ancient world. In most African societies where slavery was prevalent, the enslaved people were not treated as chattel slaves and were given certain rights in a system similar to indentured servitude elsewhere in the world.When the Arab slave trade and Atlantic slave trade began, many of the local slave systems changed and began supplying captives for slave markets outside of Africa.Slavery in historical Africa was practiced in many different forms and some of these do not clearly fit the definitions of slavery elsewhere in the world. Debt slavery, enslavement of war captives, military slavery, and criminal slavery were all practiced in various parts of Africa.Although there had been some trade from the interior of Sub-Saharan Africa to other regions, slavery was a small part of the economic life of many societies in Africa until the introduction of transcontinental slave trades (Arab and Atlantic). Slave practices were again transformed with European colonization of Africa and the formal abolition of slavery, which began in the early 19th century.The continent of Africa is one of the most problematic regions in terms of contemporary slavery. Slavery in Africa has a long history, within Africa since before historical records, but intensifying with the Arab slave trade and again with the trans-Atlantic slave trade; the demand for slaves created an entire series of kingdoms (such as the Ashanti Empire) which existed in a state of perpetual warfare in order to generate the prisoners of war necessary for the lucrative export of slaves. These patterns have persisted into the colonial period during the late 19th and early 20th century. Although the colonial authorities attempted to suppress slavery from about 1900, this had very limited success, and after decolonization, slavery continues in many parts of Africa even though being technically illegal.Multiple forms of slavery and servitude have existed throughout Africa during history and were shaped by indigenous practices of slavery as well as the Roman institution of slavery (and the later Christian views on slavery), the Islamic institutions of slavery, and eventually the Atlantic slave trade.Slavery existed in parts of Africa (like the rest of the world) and was a part of the economic structure of some societies for many centuries, although the extent varied.The ancient kingdom of Mali in the mid-14th century recounts that the local inhabitants vie with each other in the number of slaves and servants they have, and was himself given a slave boy as a "hospitality gift." In sub-Saharan Africa, the slave relationships were often complex with rights and freedoms given to individuals held in slavery and restrictions on sale and treatment by their masters.Many communities had hierarchies between different types of slaves: for example, differentiating between those who had been born into slavery and those who had been captured through war.In many African societies, there was very little difference between the free peasants and the feudal vassal peasants. Enslaved people of the Songhay Empire were used primarily in agriculture; they paid tribute to their masters in crop and service but they were slightly restricted in custom and convenience.Slavery in African cultures was generally more like indentured servitude, although in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa, slaves were used for human sacrifices in annual rituals, such as those rituals practiced by the denizens of Dahomey.Slaves were often not the chattel of other men, nor enslaved for life.The forms of slavery in Africa were closely related to kinship structures. In many African communities, where land could not be owned, enslavement of individuals was used as a means to increase the influence a person had and expand connections. This made slaves a permanent part of a master's lineage and the children of slaves could become closely connected with the larger family ties. Children of slaves born into families could be integrated into the master's kinship group and rise to prominent positions within society, even to the level of chief in some instances.However, stigma often remained attached and there could be strict separations between slave members of a kinship group and those related to the master.The volume of the slave trade in West Africa grew rapidly from its inception around 1500 to its peak in the eighteenth century.The African slave trade, estimates that roughly 6.3 million slaves were shipped from West Africa to North America and South America, about 4.5 million of that number between 1701 and 1810. Perhaps 5,000 a year were shipped from the Gold Coast alone. The demographic impact of the slave trade on West Africa was probably substantially greater than the number actually enslaved because a significant number of Africans perished during slaving raids or while in captivity awaiting transshipment. All nations with an interest in West Africa participated in the slave trade. Relations between the Europeans and the local populations were often strained, and distrust led to frequent clashes. Disease caused high losses among the Europeans engaged in the slave trade, but the profits realized from the trade continued to attract them.The growth of anti-slavery sentiment among Europeans made slow progress against vested African and European interests that were reaping profits from the traffic. Although individual clergymen condemned the slave trade as early as the seventeenth century, major Christian denominations did little to further early efforts at abolition. The Quakers, however, publicly declared themselves against slavery as early as 1727. Later in the century, the Danes stopped trading in slaves; Sweden and the Netherlands soon followed.The importation of slaves into the United States was outlawed in 1807. In the same year, Britain used its naval power and its diplomatic muscle to outlaw trade in slaves by its citizens and to begin a campaign to stop the international trade in slaves. These efforts, however, were not successful until the 1860s because of the continued demand for plantation labor in the New World.Because it took decades to end the trade in slaves, some historians doubt that the humanitarian impulse inspired the abolitionist movement. According to historian Walter Rodney, for example, Europe abolished the trans-Atlantic slave trade only because its profitability was undermined by the Industrial Revolution. Rodney argues that mass unemployment caused by the new industrial machinery, the need for new raw materials, and European competition for markets for finished goods are the real factors that brought an end to the trade in human cargo and the beginning of competition for colonial territories in Africa. Other scholars, however, disagree with Rodney, arguing that humanitarian concerns as well as social and economic factors were instrumental in ending the African slave trade.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the southern states experienced extraordinary change that would define the region and its role in American history for decades, even centuries, to come. Between the 1830s and the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, the American South expanded its wealth and population and became an integral part of an increasingly global economy. It did not, as previous generations of histories have told, sit back on its cultural and social traditions and insulate itself from an expanding system of communication, trade, and production that connected Europe and Asia to the Americas. Quite the opposite; the South actively engaged new technologies and trade routes while also seeking to assimilate and upgrade its most “traditional” and culturally ingrained practices such as slavery and agricultural production within a modernizing world.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the southern states experienced extraordinary change that would define the region and its role in American history for decades, even centuries, to come. Between the 1830s and the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, the American South expanded its wealth and population and became an integral part of an increasingly global economy. It did not, as previous generations of histories have told, sit back on its cultural and social traditions and insulate itself from an expanding system of communication, trade, and production that connected Europe and Asia to the Americas. Quite the opposite; the South actively engaged new technologies and trade routes while also seeking to assimilate and upgrade its most “traditional” and culturally ingrained practices such as slavery and agricultural production within a modernizing world.