BRAZIL'S COLONIAL STORY : THE PORTUGUESE COLONIZATION OF BRAZIL AND ANGLO - PORTUGUESE ALLIANCE ARE VERY IMPORTANT TO BRAZIL'S HISTORY.THE PORTUGUESE ALSO BEGAN EXPORTING SOME OF BRAZIL'S RESOURCES TO THEIR OWN COUNTRY ,SUCH AS BRAZILWOOD.

The Portuguese conquest of Brazil was a complex, prolonged, and partial process that many scholars argue was never fully realized. Lacking large cities, a centralized political structure, and a common language, the estimated 2 to 3 million precontact indigenous inhabitants of the Brazilian coast and interior were divided into an intricate patchwork of ethnolinguistic groups and clan-based tribes.

The Portuguese conquest of Brazil was a complex, prolonged, and partial process that many scholars argue was never fully realized. Lacking large cities, a centralized political structure, and a common language, the estimated 2 to 3 million precontact indigenous inhabitants of the Brazilian coast and interior were divided into an intricate patchwork of ethnolinguistic groups and clan-based tribes.

It was not long before other European nations wanted the opportunity to conquer and occupy parts of Brazil. Brazilwood provided a rich red dye, which was valuable in the colouring of textiles and clothing. The French and Spanish made repeated efforts at entering Brazil. The Portuguese fought determinedly against their invasion, dispatching strong fleets to clear the coast. Another one of its efforts was to establish permanent settlements. The first of these was São Vicente, established in 1532.Under the Treaty of Tordesillas, everything to the east of the line that ran from pole to pole 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands was to be Portugal's to exploit. The exact reason for Portugal's interest in having the line so far to the west is debatable, but the Portuguese may have been trying to keep the Castilians away from the sure route to the East. Very practically, the line's placement gave Portuguese vessels en route to India ample room to pick up winds and currents that took them around the southern end of Africa, a feat carried out by Vasco da Gama on his voyage of 1497-99. The Portuguese also may have known that western lands or islands lay on their side of the line. On the modern map of Brazil, in the north the line cuts across the eastern end of the Ilha de Marajó, and in the south it passes through Laguna on the coast of Santa Catarina. Because most of present-day Brazil lies to the west of the line, clearly the Portuguese expanded successfully on this initial division.The territorial aggrandizement, which is one of the main themes of Brazilian history, was both accidental and a matter of state policy. Uncertainty as to the detailed geography of South America persisted into the twentieth century, so it is understandable that Portuguese officials professed to believe into the eighteenth century that the estuaries of both the Amazon and the Río de la Plata were on their side of the Tordesillas Line. The two river systems were, in the words of the Jesuit Father Simão de Vasconcellos, "two keys that lock the land of Brazil . . . two giants that defend it and demarcate between us [Portuguese] and Castille." Several centuries of penetration along these river systems gave Brazil its distinctive shape. It could be said that today's Brazil owes its vast territory to the native Indians who served as skilled trackers, warriors, porters, food suppliers, and paddlers for the Portuguese expeditions, and to the Indians whose potential as slaves lured the Portuguese inland.The Portuguese empire at the outset was a commercial rather than a colonial one. Portugal lacked sufficient population to establish colonies of settlers throughout its maritime empire. The Portuguese practice was to conquer enough space for a trading fort and a surrounding enclave from which to draw on the wealth and resources of the adjacent country. A map of this maritime commercial domain would show a series of dots connected by sealanes rather than continuous stretches of territory. French competition forced the Portuguese shift to colonialism in Brazil. This shift involved the gradual move from trading for brazilwood to cultivating sugarcane, which required control of great expanses of land and increasing numbers of slaves. The first to burst past the Tordesillas Line were the slave hunters. The shift to colonialism was also facilitated by the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns between 1580 and 1640. Although the two governments on the Iberian Peninsula and in the Americas were kept separate, trade and travel controls became lax. An active contraband trade developed between Brazilian settlements and Buenos Aires, and Portuguese moving overland appeared in Asunción, Potosí, Lima, and even Quito.Expansion along the Atlantic coast had been gradual. Using the model of the Atlantic islands, the crown in 1536 divided the Brazilian coast into fifteen donatory captaincies (donatários ). To induce settlement, the crown offered ten leagues of coastline as personal property, a percentage of the dyewood trade, control over trade of enslaved natives, as well as the exclusive right to build mills. In 1580 Brazil comprised the area from Pernambuco in the north to São Vicente in the south. With Spanish assistance thereafter, the Portuguese expanded north to Paraíba, then west through Ceará and Maranhão against the natives and the French, until they founded Belém in 1616. Beginning in 1621, these possessions were divided into the state of Maranhão (embracing the crown captaincies of Ceará, Maranhão, and Pará) and the state of Brazil, centering on Salvador, Bahia. The reassertion of Portuguese independence under the Braganças in 1640 led to sporadic conflict in frontier areas and to policies seeking to hold back Spanish advances. In the Amazon and Río de la Plata river basins, the Spanish rather than the Portuguese had been first on the scene. The Spaniards included Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, who journeyed from the coast of Santa Catarina to Asunción in 1540, and Francisco de Orellana, who descended the Amazon in 1542.The most important Spanish advances were the mission settlements, where the Jesuits Christianized native peoples. Two areas of particular importance lay adjacent to the river systems that delimit Brazil in the south and in the north: the Paraná-Paraguay Basin in the south and the Mamoré-Guaporé Basin in the north. From 1609 to 1628, the Jesuits founded eight missions among the Guaraní peoples between the Paraná and Paraguai rivers in what is now southern Paraguay. They pressed deep into what is today the state of Paraná, between the Ivaí and Paranapanema rivers, to establish fifteen more in what was called Guairá Province.From 1629 to 1631, the Guairá missions were attacked by slave hunters, known as bandeirantes, from the Portuguese town of São Paulo. According to the governor of Buenos Aires, these attacks resulted in the enslavement of more than 70,000 Guaraní. Consequently, the Jesuits decided to evacuate some 10,000 survivors downriver and overland to sites between the Rio Uruguai and the Atlantic, in what became the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Other Jesuits fleeing the Guairá missions set up missions among the Itatín people on the eastern bank of the Rio Paraguai in what is now Mato Grosso do Sul, only to be destroyed brutally by bandeirantes in the 1630s and 1640s. By 1650 only twenty-two of forty-eight missions remained in the whole region. The Jesuits stopped the slave hunters in the south by arming and training the Guaraní, who dealt a significant blow to their oppressors in the Battle of Mbororé in 1641. This victory ensured the continued existence of the southern Spanish missions for another century, although they became a focal point of Portuguese-Spanish conflict in the 1750s. Broadly speaking, the Battle of Mbororé stabilized the general boundary lines between the Portuguese and the Spanish in the south.In the north, the Spanish had established the town of Santa Cruz de la Sierra in 1561 and from there planted missions in the Mamoré-Guaporé Basin in about 1682. Called the Mojos and Chiquitos, these mission provinces were in what is now lowland Bolivia fronting on the states of Mato Grosso and Rondônia. By 1746 there were twenty-four mission towns in the Mojos and ten in Chiquitos. The bandeirantes again carried the flag of Portugal into the region, first attacking the Chiquitos missions for slaves and then discovering gold in Mato Grosso (1718-36). Unsure where these gold discoveries were in relation to the Spanish territories, the members of the Lisbon-based Overseas Council, which administered the colonies, ordered a comprehensive reconnaissance and the drawing of accurate maps. In 1723 Francisco de Melo Palhêta led an expedition from Belém to the Guaporé, reporting to Lisbon the startling news about the numerous prosperous Jesuit missions. Moreover, the question of fixing borders had become more urgent in 1722, when a respected French cartographer placed the mouths of the Amazon and the Río de la Plata on the Spanish side of the Tordesillas Line.Because the Guaporé rises in Mato Grosso and flows into the Mamoré, which enters the Madeira, and then into the Amazon, these rivers formed a natural border. Moreover, the headwaters of the Paraguai were close and offered the possibility of linking the Amazonian and La Plata systems. In 1748 Lisbon created the Captaincy of Mato Grosso as its rampart on the Peruvian side and later in the century erected Fort Príncipe de Beira on the Guaporé. In northern Amazônia, in what were then the royal states of Maranhão and Pará, the Portuguese, worried about Dutch traders from Guiana (modern Suriname) and Spaniards from Venezuela, built fortifications at Óbidos, Manaus, Tabatinga, and on the Rio Branco and Rio Negro during the eighteenth century, thereby solidifying their claims. As it turned out, it was easier to secure the vast North region than it was the South.

The Portuguese Empire is a collection of overseas territories that were colonized by the Portuguese from the 15th to the 20th century. The precondition for the formation of the Empire was the enclosed nature of Portugal, surrounded on all sides by the Spanish kingdom. The great geographical discoveries of the late fifteenth century, the activities of the Portuguese nobility and trade elites led to the creation of the largest sea empire forthe next several centuries.

The Portuguese Empire is a collection of overseas territories that were colonized by the Portuguese from the 15th to the 20th century. The precondition for the formation of the Empire was the enclosed nature of Portugal, surrounded on all sides by the Spanish kingdom. The great geographical discoveries of the late fifteenth century, the activities of the Portuguese nobility and trade elites led to the creation of the largest sea empire forthe next several centuries.

In 1680 the Portuguese had built a fort at Colônia do Sacramento on the eastern La Plata shore opposite Buenos Aires to guard their claim and to capture a share of the contraband trade with silver-rich Potosí. According to the Overseas Council, Lisbon adopted the policy of fortifying and settling the coast below Santa Catarina, because "the continuation of these settlements will be the best means of deciding the question of limits between the two crowns."By the mid-eighteenth century, the Iberian powers were ready to admit the fiction of Tordesillas and to redraw their lines in South America on the basis of uti possidetis (that is, ownership by occupation rather than by claim). The Portuguese gave up Colônia do Sacramento, and in return received the lands of the Jesuit order's seven missions in western Rio Grande. This exchange led to the Guaraní War of 1756, which destroyed the missions and contributed to the Jesuit expulsion from Portuguese (1759) and Spanish (1763) possessions. With the Treaties of 1750, 1761, and 1777, Brazil took on its modern shape. The lines were drawn for the nineteenth-century struggles over the East Bank (Banda Oriental, or present-day Uruguay) of the Rio Uruguai and the Río de la Plata, the war with the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (1825-28), and the Paraguayan War, also known as the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-70).Thus, as a result of slave hunting, gold prospecting, and Portuguese royal policy, the Tordesillas Line became obsolete, and Portugal obtained more than half of South America. When Brazil became independent in 1822, its huge territory was comparable in size with the Russian and Chinese empires.The decline in the sugar economy cut off the smaller Northeastern cane farmers from the customary paths to higher socioeconomic status, producing a situation in which this potentially powerful segment of the population no longer had reasons to support the traditional colonial society. The cane farmers had the same social origins as the wealthier planter and mill-owner class but generally were less independent financially, and now their future was darkened. As sugar prices fell, the planters and mill owners' response was vertical integration; stages of production were consolidated under the control of fewer firms. Purchases from independent cane farmers were reduced and their lands acquired. The situation was potentially explosive. Historian Stuart Schwartz commented that "at no time in Brazilian history had the conditions for a profound social upheaval been more suitable." But it did not occur for two reasons: the cane farmers did not rebel against the sugar barons for fear of encouraging a slave rebellion, and in addition, newly discovered gold fields to the south soon beckoned to free and slave populations. The removal of pressures for change solidified the hold of the great landowners on the coastal plantations.Small deposits of alluvial gold had been exploited quietly for decades in São Paulo and to the south. The Paulistas likely found more than they revealed, fearing that the greed of the Portuguese authorities would soon strip them of their semi-independence. The discovery of gold by Paulistas in various parts of what is now Minas Gerais (General Mines), between the Serra de Mantiqueira and the headwaters of the Rio São Francisco, probably occurred between 1693 and 1695, but word filtered out slowly. The greatest concentration of deposits was along Brazil's oldest geological formation, the Serra do Espinhaço, lying in a north-south direction, throughout which it seemed that every river, stream, and brook glittered with gold. Mining camps that turned into the cities of Ouro Prêto, Mariana, and Sabará soon located in its southern end, and by 1730 diamonds were coming out of the northern reaches around Diamantina.Word of the discoveries set off an unprecedented rush, the likes of which would not be seen again until the California gold rush of 1849. The Paulistas soon found themselves competing for control with adventurers from the Northeast who streamed down the Vale São Francisco, from Portugal, and from elsewhere. By 1709-10 the Vale São Francisco had become a lawless region filled with the dregs of the Portuguese world. Considerable violence broke out between the original Paulista bandeirantes , who considered the mines theirs, and the outsiders . This fighting gave the crown authorities a reason for asserting royal control and arranging a settlement of the War of the Outsiders (Guerra dos Emboabas, 1708-09). Many Paulistas moved on to new gold discoveries in Goiás and Mato Grosso.The discoveries shifted Brazil's center of gravity away from the Northeastern coast and toward the South and West. The loser would be Bahia, which in 1763 lost the viceregal capital to Rio de Janeiro, as power followed wealth. The population also shifted, as would-be miners and those who would profit from the mines arrived with their native or African slaves. The Jesuit Father André João Antonil (whose Italian name was Giovanni Antonio Andreoni) wrote the best contemporary study of Brazilian economic and social conditions. He said that by 1709 some 30,000 people were in Minas Gerais. In the next decades, the population swelled. The 1735 tax records showed a total of 100,141 slaves, among whom there were numerous natives. By 1782 Minas Gerais's population of 319,769 included 166,995 blacks, 82,110 mulattoes, and 70,664 whites. The state had the largest concentration of population in the viceroyalty of Brazil: 20.5 percent of Brazil's 1,555,200 people.

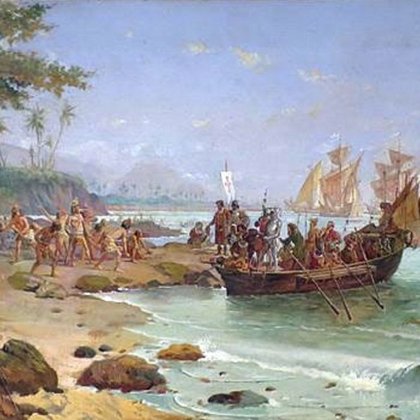

Since the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade during the fifteenth century, Portuguese traders and explorers were interacting with the indigenous peoples of what is modern day Brazil. The Portuguese involvement in South America, and particularly in Brazil, was initiated by the decree made by Pope Alexander VI in 1493, which denoted a “demarcation line.” The line separated land in the West Indies and South America into east and west. The east was granted to the Portuguese crown and the west to the Spanish crown.

Since the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade during the fifteenth century, Portuguese traders and explorers were interacting with the indigenous peoples of what is modern day Brazil. The Portuguese involvement in South America, and particularly in Brazil, was initiated by the decree made by Pope Alexander VI in 1493, which denoted a “demarcation line.” The line separated land in the West Indies and South America into east and west. The east was granted to the Portuguese crown and the west to the Spanish crown.

The early population consisted predominantly of unruly males, who knew no law but their own whims and who drove their slaves hard in an existence that historian Charles Boxer tagged as "nasty, brutish, and short." Many African slaves reacted by running away to form hiding places called quilombos and were pursued by roughneck "bushwhacking captains" (capitães do mato ). However, during the first decades life could not have been easy for anyone. Items such as meat, corn, flour, and rum were rare and costly. The first local supply of hogs and chickens appeared only in 1723, and a flask of salt could cost as much as half a pound of gold.Although long inhabited by prehistoric tribes and settlements, Brazil underwent an entirely new kind of habitation during the 16th century. In April 1500, the Portuguese arrived on the Bahian shores of Rio Buranhém, under the direction of Pedro Alvares Cabral. These ones documented seeing indigenous inhabitants upon landing on the beach, who greeted them with peace offerings of headdresses made from parrot feathers.Although the Portuguese sailors stayed for only nine days, the indigenous people soon became fascinated by the iron tools used, the Catholic mass service observance and the alcoholic beverages that they observed. Because of this perceived interest in the Roman Catholic religion, the Portuguese assumed that these ones would quickly convert to Christianity once educatedBy the last decades of the eighteenth century, however, the cities of Minas Gerais were graced with impressive baroque and rococo churches, multistoried homes and shops, and grand public buildings. Poets and musicians enlivened the cultural scene. Some 3,000 musicians, mostly mulattoes, played fine baroque pieces, often in churches built by architect Antonio Francisco Lisboa (also known as "O Aleijadinho") and under ceilings painted by Manuel da Costa Ataíde.The overland trails from São Paulo and from Paratí were superseded by ones connecting to Rio de Janeiro. The new viceregal capital sent African slaves and European merchandise to Minas Gerais and received the heavily laden chests of gold and diamonds en route to Lisbon. Rio de Janeiro also served as the supply base for the newly created captaincies of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande de São Pedro, passing their livestock products on to Portugal. Those captaincies were linked overland to São Paulo and Minas Gerais via the livestock trails that ran northeast from the pampas of what was later called Rio Grande do Sul to Sorocaba in São Paulo Province.Ranching had developed in the Northeastern interior as an adjunct to the sugar economy and in the South as the legacy of the Jesuit missions. In the eighteenth century, ranching was an increasingly important part of the overall colonial economy. The moving frontiers that it created drew the interior into effective relationships with European-oriented Brazil. From the interior of Maranhão, southeast through Piauí, Ceará, Pernambuco, and Bahia, then west into Goiás, and on down to Rio Grande do Sul, a set of cowboy (vaqueiro ) subcultures evolved that still mark local traditions. It was an age of leather in which the horse was the center of life. Many, perhaps most, of the vaqueiros were native Indians, mestizos, African slaves, and mulattoes. In the northern and central areas, slaves and free men worked together unsupervised for months at a time. In the South, the gaucho culture, mixing native, Spanish, and Portuguese bloodlines and traditions, took hold throughout the pampas of the Río de la Plata up into Rio Grande do Sul. In the latter state, by the mid-1820s cattle had driven out wheat farming, and the mounted gaucho with his bolas, knife, maté tea, and open-fire barbecued beef became characteristic.Although gold mining weakened the dominance of sugar and seemingly stimulated the cattle industry, it did not totally supersede export agriculture. It displaced sugar as the colony's leading economic activity, but during the eighteenth century the value of gold exports never surpassed the value of sugar-led agricultural exports. Even so, gold did have serious long-term effects on Portugal. The fall in the value of Portugal's colonial products in the seventeenth century had made it difficult to obtain sufficient currency to purchase merchandise from northern Europe. In response, Portugal had begun to develop industries to meet its local and colonial requirements. The discovery of gold provided needed currency.In 1703 Portugal signed the Methuen Treaty with England, giving English woolens preference in Portuguese markets in return for a favorable tariff on Portuguese wines. This seemingly simple arrangement ended the move toward industrial development, drained Brazilian gold out of Portugal, and gave England its increasing dominance over Portugal and Brazil. The gold and diamond chests arriving at the royal treasury in Lisbon immediately were dispatched north to pay for imported cloth and manufactured goods. Local Portuguese producers could not compete with cheaper foreign prices. Furthermore, English vessels anchored in the Tagus River in the Iberian Peninsula snatched large quantities of gold from under the noses of Portuguese authorities. Instead of Brazil's wealth being used to develop Portugal and its colonies, it helped finance the English industrial revolution and Portugal's eighteenth-century struggles to secure Brazilian boundaries.Even though an immense amount of wealth was sent abroad, much stayed in Brazil to build urban public works, such as fountains, bridges, buildings, and churches; to endow some charitable foundations, such as hospitals; and to finance the elaborate contraband trade with the Río de la Plata and Alto Perú (Upper Peru, or present-day Bolivia). However, it did not improve the condition of the poor; generate a prosperous middle class; improve agriculture, education, or industry; or produce lasting reform.In 1732 António Rodrigues da Costa, a member of the Overseas Council, warned the crown that the heavy colonial taxes would one day lead the colonists to cast off their loyalty. It was obvious to Rodrigues da Costa that the "larger and richer" would not accept forever being ruled by the "smaller and poorer." In 1738 royal adviser Dom Luís da Cunha suggested secretly to King João V that he take the title "emperor of the west" and move his court to Rio de Janeiro, which he argued was better situated than Lisbon to control the Portuguese maritime and commercial empire. Rather than heed such advice, however, the monarchy tried at mid-century to gain more control, stop the massive outflow of gold, and contain the British. Beginning in 1755, Marquês de Pombal (Count Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, as secretary of state for overseas dominions, shaped a series of reforms that gave chartered companies a monopoly of the Brazil trade, encouraged national manufacturers, and worked to make commercial relations with Britain less dependent and more reciprocal. His goal was to revitalize the state and to break the stranglehold of British credit. He closed Brazilian ports to all foreign ships and hired foreign military experts to organize Brazil's defenses. To promote agricultural growth, Pombal distributed coffee and mulberry seedlings and also advocated production of indigo, flax, cotton, cocoa, and rice. Iron mining and smelting got underway in São Paulo, and shipbuilding and its attendant trades in Bahia and Rio de Janeiro increased. With the British seizure of Havana and Manila during the Seven Years' War (1756-63), the Portuguese wondered if Rio de Janeiro would be next. The crown responded with four goals: secure the borders, populate them for self-defense, defend the ports, and make the mines profitable.

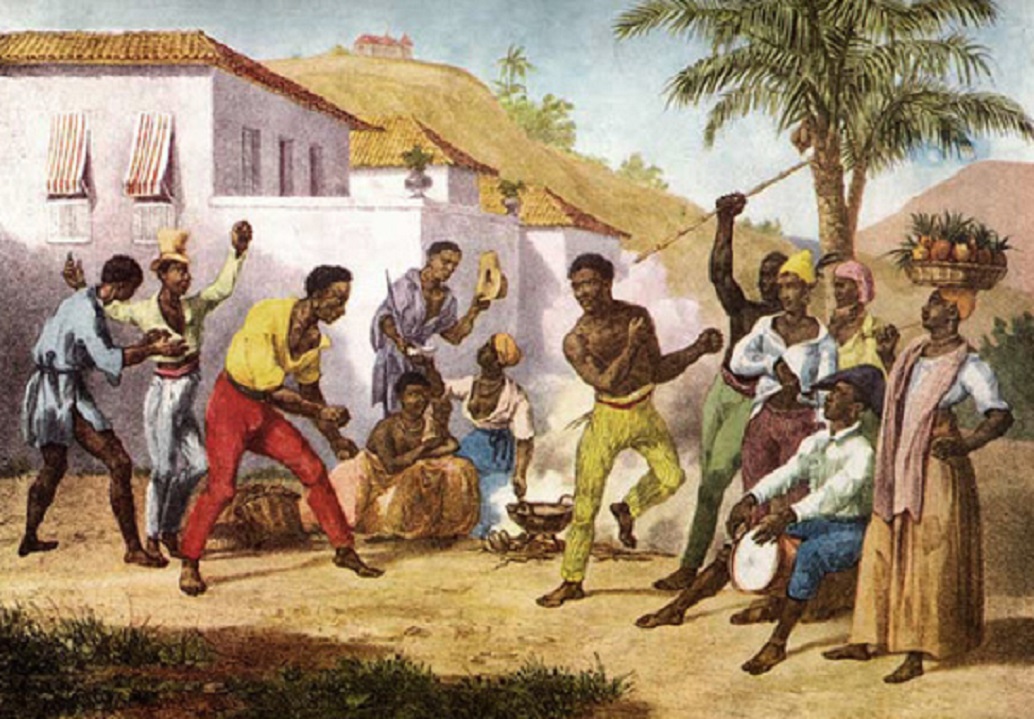

Overall, the Portuguese involvement in Brazil was for economic as well as personal reasons. The three major areas of interaction show self-interest: The Portuguese cultural motives regarding Religion displayed a disinterest in native culture as they brought Catholicism to Brazil but were not willing to embrace cultures they encountered. The Physical force that enslaved many natives was for the lucrative sale of produced goods from slave labor, the kind of labor that Portuguese did not have to perform.Capoeira's origin dates back about 500 years to the beginnings of Brazil's slave trade period. Throughout the 488 years of slave trade in Brazil, various tribes from West and Central Africa.

Overall, the Portuguese involvement in Brazil was for economic as well as personal reasons. The three major areas of interaction show self-interest: The Portuguese cultural motives regarding Religion displayed a disinterest in native culture as they brought Catholicism to Brazil but were not willing to embrace cultures they encountered. The Physical force that enslaved many natives was for the lucrative sale of produced goods from slave labor, the kind of labor that Portuguese did not have to perform.Capoeira's origin dates back about 500 years to the beginnings of Brazil's slave trade period. Throughout the 488 years of slave trade in Brazil, various tribes from West and Central Africa.