FRENCH REVOLUTION BEGAN IN 1789 LASTED FOR A DECADE AND THE SUBSEQUENT NAPOLEONIC WAR CHANGED THE FACE OF EUROPE.IN AUGUST 1792 ,THE ROYAL COUPLE (KING LOUIS XVI AND HIS WIFE MARIE ANTOINETTE) WAS ARRESTED AND IMPRISONED.KING LOUIS XVI (1754-1793) EXECUTED ON JANUARY 21,1793 AND THEY EXECUTED HIS WIFE MARIE ANTOINETTE.

King Louis XVI ( 1754 – 1793), born Louis-Auguste, was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. His wife Marie Antoinette was the last Queen of France before the French

Revolution. She was born Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna on November 2,

1755, and she was the Archduchess of Austria and one of the children of

Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I. When her husband

Louis XVI became king of France, she gained the title of Queen of

France and Navarre. In 1793, she was convicted by the Revolutionary

Tribunal of high treason and was executed by guillotine on October 16,

1793. Below are 44 head-rolling facts about the former French Queen.

King Louis XVI ( 1754 – 1793), born Louis-Auguste, was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. His wife Marie Antoinette was the last Queen of France before the French

Revolution. She was born Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna on November 2,

1755, and she was the Archduchess of Austria and one of the children of

Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I. When her husband

Louis XVI became king of France, she gained the title of Queen of

France and Navarre. In 1793, she was convicted by the Revolutionary

Tribunal of high treason and was executed by guillotine on October 16,

1793. Below are 44 head-rolling facts about the former French Queen.

The French Revolution began, in 1789 and lasted for a decade. In that time, the citizens of France demolished and rebuilt their nation’s institutions and the changes they wrought, often bloodily, persist as a reminder of the power of the people.By 1787, France was teetering on bankruptcy and the price of a loaf of bread had skyrocketed to a week’s wage for the average worker. This was practically all people ate and so going without or replacing it with something else, say, cake, wasn’t an option. Even if Marie Antoinette never suggested anything of the sort (and most historians agree she didn’t), the fact remains that making your subjects’ single source of sustenance exorbitantly expensive is a sure way to ensuring they lose their minds and, shortly thereafter, you lose your head. Bread prices also inspired a Women’s March on Versailles in October 1789.When things really heated up in France, Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette and the family, afraid for their safety, tried to escape the country.The revolution and the reign of terror that ensued, led by Robespierre, have caused thousands of casualties: over 18,000 people were beheaded in all, although some historians estimate the deaths to go as far as 40,000. But it’s a case of the biter bit because Robespierre himself was executed by the guillotine , on July, 28th of 1794. Louis XVI. He experienced first-hand an “improvement” of the guillotine that he had contributed to. Indeed, word is that he was the one to suggest that a triangular blade might make the guillotine more efficient.The event that is commonly known as marking the beginning of the French Revolution is the storming of the Bastille prison. But a fun fact linked to this is that there were actually only seven prisoners in the prison that day! One of them being the infamous Marquis de Sade, who gave his name to sadism.And another fun fact about the French Revolution and Bastille is that the building was torn down by hand by the revolutionaries since most of them were peasants who didn’t have access to explosives or more destructive weapons. In fact, the attackers were way more interested in the stock of arms and powder kept within the walls of the prison than in the prisoners.Marie-Antoinette was despised during her life, but she is more loved today and more famous than any other French queen. This is why some historians have tried to rehabilitate her reputation: for instance, she was believed to have said, when the Parisians came to Versailles to ask for bread: “If they can’t have bread, let them have cake“. But, very likely, she never said that, and the rumors of the time distorted who she truly was.In fact, the last words she is supposed to have said are “I’m sorry“, for stepping on the executioner’s toe.How sad! And another fun fact about the French Revolution and about the most famous Queen of France is that Marie-Antoinette supposedly gave the executioner a purse full of gold coins, to make sure that the blade was sharp and that her death was going to be clean and quick. Like the King, she was executed at Place de la Concorde.Long before the Revolution, the monarchy was subject to public derision, namely through racy pamphlets known as libelles. These frequently pornographic publications intended to erode the power the royal family held over the population and didn’t hold back when it came to their intimate affairs. The reasons why the couple appeared not to have consummated their marriage during its first seven years being a popular topic for speculation. Even then, women had a harder time with the media than men and Marie Antoinette bore the brunt of the attacks. However, the king’s many perceived inadequacies, sexual and otherwise, were roundly mocked.In most imaginations, when the guards of the Bastille were overwhelmed on July 14th, 1789, a flood of wrongly interred prisoners poured into the streets of Paris. The real scale of the breakout, however, is somewhat disappointing: only seven people were being held captive at the time. One of them was the notorious Marquis de Sade, but still. In fact, it was the huge store of arms and gunpowder that was of interest to the revolutionaries. More impressively, the fortress was dismantled entirely by hand and the bricks were given away or sold as symbols of tyranny’s inevitable downfall.As strange as it might seem for those of us who grew up with textbooks and national galleries filled with portraits of loved and loathed monarchs, unless you were living in Versailles at the time, it was unlikely you had a clue what Louis XVI or Marie-Antoinette really looked like. Keeping their true identities hidden from the lower classes in case they one day needed to escape a bloody revolution could have been history’s most brilliant piece of forward planning had the king not had his face stamped all over the nation’s gold coins. Remarkably, they still made it to the border before being identified.During the Revolution, approximately 18,000 people were beheaded by the ‘national razor’, though some estimates run as high as 40,000. Louis XVI was the first of the royal couple to go on January 12th, 1793, but his execution was only secured by a narrow majority: 361 votes for and 288 against. Unluckily for him, even his cousin, Louis Philippe d’Orléans, didn’t want to see him live. The last recorded words of Marie Antoinette on October 16th, 1793, were ‘I’m sorry’ – not a reference to any crimes against the republic but a polite necessity after having trod on the executioner’s foot.

Even the king’s close cousin, the Duke of Orleans, was among

those who voted for the king’s death. Others who voted for his death

included Robespierre, Marat, Danton.Three hundred and sixty-one votes were needed for a simple majority and in the end 361 deputies voted unconditionally for death. The deputies entertained a series of appeals in the days following, but the measures to stay the king's execution failed. On January 20, 1793, the deputies decreed Louis’ guilt and his punishment by death; there would be no reprieve of his execution. The following day, the sentence against Louis was carried out.

Even the king’s close cousin, the Duke of Orleans, was among

those who voted for the king’s death. Others who voted for his death

included Robespierre, Marat, Danton.Three hundred and sixty-one votes were needed for a simple majority and in the end 361 deputies voted unconditionally for death. The deputies entertained a series of appeals in the days following, but the measures to stay the king's execution failed. On January 20, 1793, the deputies decreed Louis’ guilt and his punishment by death; there would be no reprieve of his execution. The following day, the sentence against Louis was carried out.Louis ascended to the French throne in 1774 and from the start, he was confronted with the serious financial problems that he had inherited from his grandfather, King Louis XV.In 1789, in the last attempt to resolve his country's financial crisis, Louis assembled the States-General, a national assembly that represented the three "estates" of the French people--the nobles, the clergy, and the commons.He traveled in the mayor's coach accompanied by his confessor, Henry Essex Edgeworth de Firmont, and by Lieutenant Lebrasse. The Paris Commune, the revolutionary municipal government, had stationed guards four deep along the coach's path, and the journey passed mostly in silence as Louis prayed. By 10 am, Louis’ coach arrived peacefully at the Place de la Révolution, where some twenty thousand people had gathered.The coach approached the scaffold (which stood approximately where the Obelisk decorating the Place de la Concorde stands today). Louis dismounted the carriage and removed his coat and collar. The executioners bound his hands, led him up the stairs, and cut his hair.Louis addressed the crowd in a clear voice, “I die innocent. I pardon my enemies and I hope that my blood will be useful to the French, that it will appease God’s anger.” At this point, the drums began to roll, and Louis’ final words were inaudible.He was strapped to a plank, guided through the guillotine’s “widow's window,” and was executed. The execution of the king by his people was a transformative moment in European politics.All efforts were made to ensure that there would be nothing left of the king. Louis’ head and body were taken swiftly to the Madeleine Cemetery where he was buried in a deep grave in a wooden coffin, which was covered in quicklime to accelerate the decomposition process, and quickly covered over.Critiques of Louis under the Old Regime and in the early years of the Revolution tended to portray Louis as a good king poorly advised. Events in the early years of the Revolution aligned with this view. Historians generally agree that Louis XVI was reform-minded and earnestly wanted the best for his people.But the king had grown dissatisfied with the constraints of Constitutional Monarchy. In June 1791, he tried to escape Paris and flee to the Austrian Netherlands, where he could mount a resistance to the Revolution. Louis and his family very nearly made it, but they were recognized and arrested in the town of Varennes and escorted back to Paris by six thousand national guardsmen. As they made their way back to Paris, entire villages of armed men and women and children came out to meet the procession, to cheer the nation and harangue the king.The flight to Varennes marked a turning point. The king had tried to abandon his people. Worse yet, Louis had left behind a letter in which he renounced the Revolution and claimed that all of his previous support for revolutionary legislation had been made under duress. He had lied; he had broken faith with his people.The shift in public opinion was swift. Newspapers of a range of political positions critiqued and lampooned the king. Louis’ name, image, and insignias were removed from public view, like shop signs, inns, and other public buildings. The first sustained talk of a republic echoed through Paris in the weeks after the king’s attempted flight.By the summer of 1792, France was at war with Austria and Prussia, who were advancing swiftly into French territory. In August, the people of Paris and the national guardsmen began an insurrection, and Louis and his family were forced to flee the Tuileries Palace and seek the protection of the Legislative Assembly on August 10.The Assembly initiated thorough and deliberate legal proceedings against the king, charging him with “a multitude of crimes to establish [his] tyranny,” including treason and counterrevolutionary activity.Shortly before the trial began in December, more documents from a safe in the Tuileries palace were uncovered. The 625 documents in the armoire de fer provided evidence of Louis’ efforts over the past three years to destroy the Revolution: instructions for his ministers to lie to the Legislative Assembly, attempts to bribe deputies, and efforts to obstruct the constitution all appeared in the king's own hand.Following the state’s case and the king’s defense, the deputies prepared to vote on three questions: the king’s guilt, his punishment, and whether the punishment should be put to a national referendum before it was carried out.On January 15, 693 of the 745 deputies voted “yes” that the king was guilty. The deputies voted next on whether the punishment should be put to a national appeal, and 424 deputies voted against the appeal. The vote on the king’s death took place on January 16th, and the vote stretched late into the night and the following day.A single cart drawn by two huge white horses travels through the streets of Paris as a ravenous crowd fights to catch a glimpse of the woman within. Her hands are bound but her back is straight and her expression is hard and proud. Her famous blonde hair has turned a premature grey, and the figure that was once dainty and slender has grown large with rich palace meals. She sits frozen in place while the crowd spit and yell insults at her. Her name is Marie Antoinette, formerly the queen of France, and the people are screaming for her blood.As the cart reaches Place de la Révolution, Marie catches a glimpse of her one-time home, the grand Tuileries Palace, and her face crumbles. Sudden hot tears stream from her eyes and her body trembles. But in a moment she has recovered. She forces the tears back, veils her emotion and steps from the cart with purpose. Draped in a white cotton gown and white cap, she has been stripped of all the finery she was once renowned for, but Marie knows, even without a crown, she is still a queen; that is all she ever was. With her head held high, she moves with majesty towards the guillotine. The time is 12.15pm when she rests her neck upon the block. The blade is released, and in a moment the illustrious and terrible life of the most hated woman in France is ended.The moment Marie stepped through the doors of Versailles she was surrounded by courtiers far older and more experienced than her, who opposed everything she represented – an alliance between France and Austria. Marie was denied the common method any young queen would employ to solidify her position – producing an heir – as Louis was unable to consummate the marriage for seven long years. Her awkward and humiliated husband shrank smaller and smaller under the knowing smirks of the members of court, but shrinking was the last thing Marie had on her mind.Marie dressed for success. She robed herself in a huge array of luxurious silk dresses, placed her dainty hands into scented gloves, stood strong in high heels and literally made herself taller with her towering pouf hairstyle. She broke court traditions, abandoning heavy make-up and replacing wide-hooped panniers with simple feminine dresses that complemented her full figure. Her costume was strategy for survival; it sent a loud and clear message – “I can do exactly what I please” – and this message filtered into her lifestyle. As her husband slept, she partied into the early hours, gossiping with friends and attending masked balls. She commissioned a painting of herself riding in the style of a man and she even dared to own a property independently of her husband. The young Austrian was making waves; if tradition wouldn’t accept her, then she would smash it to pieces.The older generation at court didn’t like this one bit – a frivolous, air-headed girl they could handle, but an ambitious and stubborn foreign woman who didn’t know her place? That was far more dangerous. Before she had even finished her teens Marie was making enemies. What was originally the gossip of court filtered outside the palace walls and filled the pages of the libelles, the slanderous pamphlets published across France. To the writers and readers of these, the lack of an heir obviously meant that the queen was courting other men, and her excessive wardrobe came across as grandiose at a time when her people were starving. The revolutionary propaganda that was already bubbling leapt upon this image of an idiotic, shameless queen and refused to let it go. Little did Marie know, while she focused on cementing her place as queen, the destruction of the royal authority had already begun, and she was to serve as the centrepiece.On 14 October, Marie was taken to face her enemies at the

Revolutionary Tribunal. The charges against her were more an attack on

her person than her politics; the headlines that had filled the libelles

were presented as fact. They accused her of organising orgies in

Versailles, orchestrating the massacre of the Swiss guards, sending

France’s money to Austria and, most appalling of all, sexually abusing

her own son. At this she refused to respond, simply uttering: “If I make

no reply, it is because I cannot. I appeal to all mothers in this

audience.” Her unbelievable defiance and strength despite the horrors

she had endured was remarkable, but the verdict had been decided before

she even entered the room. Guilty.In her execution, Marie displayed the courage and markings of a true

queen until the end. But that was the problem exactly: she was a queen

in every sense of the word. She was born to be a queen, trained to be a

queen, had performed her duties as queen throughout her entire life –

but France didn’t want a queen. Her lifeless body was dragged from the

guillotine and tossed in a cart and her head was thrown between her

legs. Her remains were dumped in an unmarked grave, but the memory of

Marie Antoinette would live on as France’s hated, but eternal, queen.After the royal couple were finally able to produce an heir, the queen transformed from a party girl to a stern, self-controlled woman. But this change came too late; the revolution gaining speed outside the palace walls had already decided exactly what sort of person she was. The country was in debt, huge debt, and it was the common people who were feeling the sting. Marie, deemed responsible thanks to her trivial expenditures, was dubbed ‘Madame Déficit’. This was not without truth – Marie spent more than any other person in France, bestowing her favourites with gifts and reluctant to tax her aristocrat chums. The expenses of court were huge, and outside the people were starving.But Marie was fighting her own battles. Her husband, after suffering from bouts of depression, had withdrawn his power in government and she was the only one able to cement the authority of monarchy in his place. Despite her own mother’s advice to avoid meddling in politics, the queen emerged as a powerful political force, and without the support of her husband was forced to grapple for the power of the monarchy against an assembly growing less and less faithful.On the surface she was iron, but underneath Marie was shaken by the uprising outside the palace walls. She had made hasty efforts to reduce her expenditure, stripping her room of her fineries, but these efforts went largely ignored. When she emerged in her box at the theatre, she was hissed at so horrifically by the crowd that she began to completely withdraw from the woman she once was. She stayed away from parties, from balls, even from the king’s council chamber, and devoted her attention to her children, terrified that if she involved herself further, she would be held responsible for tearing France in two.Since her birth, Marie Antoinette had been primed and prepped to become a queen. Born the 15th child of the formidable Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, the only woman to serve in the role, her mother was strict and distant with her youngest daughter, determined she should serve as a bridge between the two great warring dynasties of Habsburg and Bourbon. Maria was a clever woman, and she ensured that her beautiful young daughter became the talk of the French capital. The French king Louis XV was convinced, and arranged the marriage of the young archduchess to his grandson and heir, Louis XVI.The two great leaders, concerned with cementing their individual power, had not taken into consideration the compatibility or the happiness of the children involved. The young archduchess was undoubtedly beautiful, with her slender figure and gleaming blonde hair, but she was also incredibly vivacious. Caring little for books and education, she was a thrill-seeker, and although she didn’t know languages or mathematics, she knew people, and was an expert at getting them to do exactly what she wanted. The young dauphin, meanwhile, was a quiet and timid boy. Strictly religious, he read often and engaged in quiet pursuits. He loved deeply, but he feared even more so, and most crucially, he was a man who could be easily convinced by loud, persuasive people , his new wife was one such person.

During the French revolution there was a lot of death and violence. One person who got caught in the middle of it all was David’s colleague. Marat was a violent man who was always eager to jump in the fight. He was viewed as a patriot while others deemed him more of a ranting lunatic . Charlotte Corday, a Royalists thought the later. When Marat was at home alone sitting in his tub like most evenings, due to his horrible skin condition, he let Corday into his humble lobed. Caught off guard, Corday stabbed Marat to death. The painting tells the whole story. The “Death of Marat” (1793) shows that of a healthy young man resting in the tub, his face is that of pain and remorse as he gives his last breath. Right below his abdomen you can see the vivid red that soaks his sheet and stains the water, hinting at a foul play cause of death.

During the French revolution there was a lot of death and violence. One person who got caught in the middle of it all was David’s colleague. Marat was a violent man who was always eager to jump in the fight. He was viewed as a patriot while others deemed him more of a ranting lunatic . Charlotte Corday, a Royalists thought the later. When Marat was at home alone sitting in his tub like most evenings, due to his horrible skin condition, he let Corday into his humble lobed. Caught off guard, Corday stabbed Marat to death. The painting tells the whole story. The “Death of Marat” (1793) shows that of a healthy young man resting in the tub, his face is that of pain and remorse as he gives his last breath. Right below his abdomen you can see the vivid red that soaks his sheet and stains the water, hinting at a foul play cause of death.The French Revolutionary War represented continuity in European diplomacy from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, but witnessed considerable change in the way that war was waged. The influence of Revolutionary and Napoleonic France depended on the nature of its relationship with the other European states. Satellite states were transformed considerably, whereas allied and client states experienced only a degree of ideological and practical transformation. French territorial objectives from 1792 to 1807 followed a relatively traditional pattern, seeking either direct or indirect influence in central Europe and the Italian states. The eventual response to Napoleonic hegemony was the understanding that cooperative efforts outweighed individual interests in order to bring the wars to a conclusion. The result was victory over Napoleon and the creation of a new diplomatic system that incorporated individual interest into a balance-of-power system. he French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars occupied almost twenty-five years of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century. They represented the first general European war since the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars represented continuity in European alliance systems and ideologies with the notable exception of the first two years of the French Republic (1792–1794). During this quarter century, six European coalitions challenged French expansion. France too created alliances to counter these opposing coalitions. Indeed these coalitions and alliances represented continuity, rather than radical change, in the international system.As the war progressed, the radicalization of the French government meant a radicalization of its policies toward its enemies. In some cases, this translated into an existential threat for German princes on the west bank of the Rhine and for the Austrian Netherlands, which had been in Habsburg possession since 1714. The eventual incorporation of these territories into Revolutionary France often led to French cultural domination in regions that neither possessed a French identity nor ethnicity. In some cases, such as that of the Dutch revolutionaries in Holland, elements of the local population welcomed the arrival of the French, only to discover that their role was subsequently subordinated to French interests. Italian revolutionaries in Lombardy and Venetia, for example, actively supported the French armies, only to find their cities pillaged in the first months of occupation.The Enlightenment produced a European discourse on constitutions and rights that emerged in virtually every state. The goals of reformers and later revolutionaries were shaped by their respective customs, cultures and histories. The arrival of French armies in these diverse parts of western and – subsequently – central Europe brought initial opportunities to reform the administration and laws, but direct and indirect French influence often proved incompatible with local notions of change. The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars thus involved changes to European governments and societies, yet these alterations were only made possible by successful diplomatic and military campaigns.From the conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession and the death of King Louis XIV (1638–1715), his successor, Louis XV (1710–1774) , exported French power through the European system by establishing and developing alliances with other major powers in pursuit of dynastic goals . This was in contrast to the approach of his great-grandfather, who had faced a European coalition in virtually all of his wars. French participation in the War of the Polish Succession (1733–1738), the War of the Austrian Succession (1742–1748), and the Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was part of the general European competition for influence in Italy, the Holy Roman Empire and the colonial world . After 1763, France fought only one war, the American Revolution , in alliance with Spain and the Netherlands and against Britain. The latter conflict, however, did not result in a general war on the European continent, but was limited to campaigns overseas. This period of relative peace resulted largely from the Habsburg-Bourbon condominium, the political alliance between France and Austria, which represented a radical change in European politics beginning in 1756. Indeed, France stood in a close alliance with Spain from 1700. On three separate occasions, the two kingdoms formalized their dynastic relationship in the form of military agreements referred to as the Bourbon Family Compacts. These were strategic alliances between France and Spain to limit Britain's overseas ambitions and to challenge Austria's Habsburg possessions in Italy.After 1763, the Family Compacts and the Habsburg-Bourbon relationship maintained peace on the continent. When in 1772 Russia, Austria and Prussia partitioned Poland , French opposition to the carving up of that kingdom did not result in war. Plagued by financial crisis and a severely reduced army, Louis XV could not transform his vehement hostility into action.1 War with Britain in 1777 was only embarked upon because it offered the potential to regain lost colonial territories and harm Britain by removing its most productive colonies. There was no military campaign on the European continent because Britain lacked any effective means to project its power across the Channel. Austria and Prussia had no interest in that conflict, and in any event Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia (1712–1786) and Joseph II of Austria (1741–1790) prepared to square off in 1778 over Bavaria.

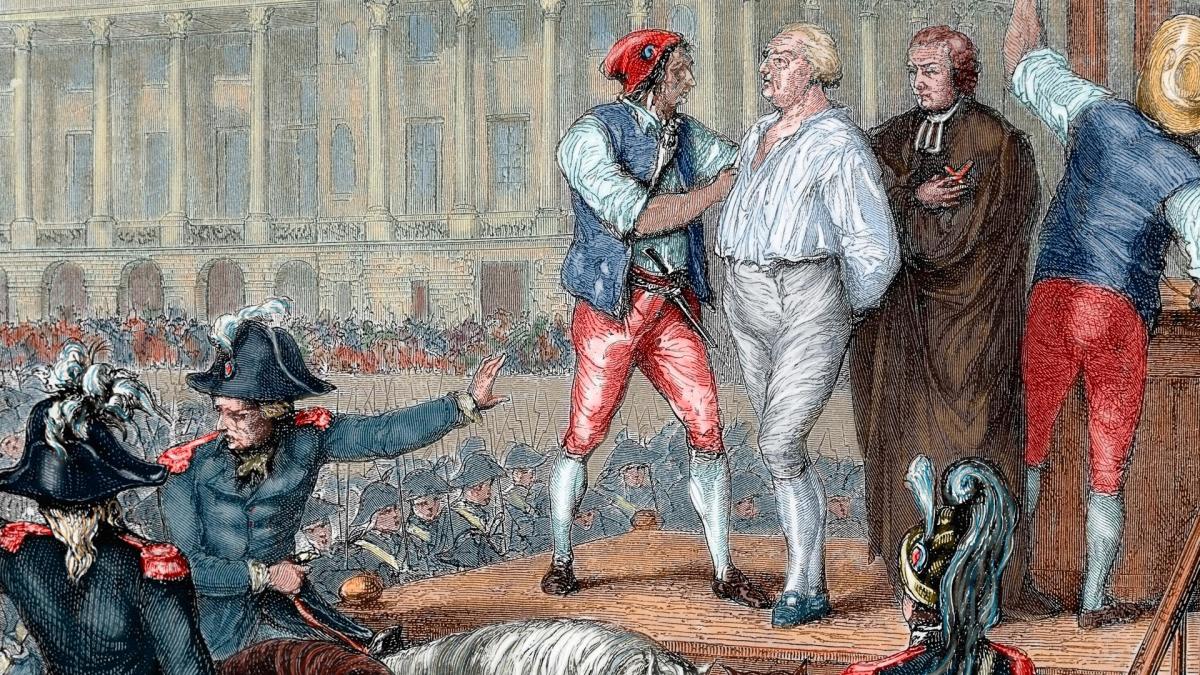

Execution of King Louis XVI (1754-1793) on January 21, 1793. Paris.On the cold, foggy morning of January 21, 1793 French King Louis XVI made the hour and a half journey through the city of Paris from the Temple, the fortified medieval monastery where he was imprisoned, to the Place de la Révolution, where the scaffold for his execution was assembled.On this day the French revolutionary politicians condemned the King

Louis XVI to death because he had, they claimed, betrayed the country

and committed crimes against the state. This conviction of the king was

brought by the highest political authority in France at that time, the

so-called National Convention a kind of parliament that also had

executive power as the state government.

Execution of King Louis XVI (1754-1793) on January 21, 1793. Paris.On the cold, foggy morning of January 21, 1793 French King Louis XVI made the hour and a half journey through the city of Paris from the Temple, the fortified medieval monastery where he was imprisoned, to the Place de la Révolution, where the scaffold for his execution was assembled.On this day the French revolutionary politicians condemned the King

Louis XVI to death because he had, they claimed, betrayed the country

and committed crimes against the state. This conviction of the king was

brought by the highest political authority in France at that time, the

so-called National Convention a kind of parliament that also had

executive power as the state government.

The short-lived War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–1779), also known as the "Potato War", demonstrated that peace and stability in western Europe led to increasing tensions in eastern Europe, beginning with the partition of Poland in 1772 and continuing through to the French Revolutionary Wars.2 The Russians mediated the Peace of Teschen, which ended the Austro-Prussian conflict in 1779. It provided for the status-quo ante with the addition of Russian guarantees for the stability of the Holy Roman Empire. It is clear that the years following the accession of Catherine II (the Great, 1729–1796) to the Russian throne in 1762 were characterized by a central European focus. She succeeded in convincing Prussia and Austria to participate in her plans for Poland, and then intervened in German affairs as a peacemaker. Furthermore, she utilized her relationship with the Austrian monarchy to bring about a coalition war against the Ottoman Empire in 1787. The Russo-Austro-Turkish War (1787–1791) began as a disaster for Austria and a great success for Russia.3 In any event, this war immediately preceded the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars. Several historians have argued that the French Revolutionary Wars were fought within the same general European context as preceding conflicts.The wars of the eighteenth century were fought for dynastic interests. Viewed in terms of state power, the continental and colonial wars represented the unfolding of European conflicts on a global scale. In most cases, European wars extended to several continents.5 Indeed the French and Indian War (1754) escalated into the general European conflict of the Seven Years' War. The consequences of increasing European global power meant that resources had to be carefully allocated, and alliances cultivated to permit the pursuit of dynastic claims in Europe. Even temporary coalitions, such as between Russia, Austria and Prussia in 1772, or between Russia and Austria in 1787, did not create permanent relationships in regions of Europe that offered enormous territorial opportunities. Coalitions were marriages of convenience in the eighteenth century. The only alliances that lasted beyond the duration of any particular conflict were the dynastic arrangements between France and Spain at the beginning of the eighteenth century, and between France and Austria at mid-century. Britain, Prussia, Russia and Austria only interpreted alliances in the short term, and this subsequently severely hampered their ability to provide a united front against Napoleonic France.At the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, attention remained focused on events in the Balkans, on growing tension between Prussia and Austria, and on the recent suppression of revolutions in the Netherlands and Belgium. The States-General overthrew the Dutch monarchy in 1787, leading to Prussian military intervention. In 1788, rebellion against Josephinian reforms in the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium) led to military repression. This was the extent of the western focus. In central Europe, however, Prussia had agitated rebels in Belgium and disrupted Austrian interests in Poland. Tensions grew and war between Austria and Prussia appeared imminent in 1790. The death of Joseph II and the accession of his brother Leopold II (1747–1792) calmed tempers. Nevertheless, it appeared to many that the conclusion of war with the Turks would be followed immediately by a confrontation between the two German powers.6 Equally, cracks appeared in the Habsburg-Bourbon pact as a result of Austria's Polish policies, as well as Joseph's desire to trade the Austrian Netherlands for Bavaria in 1784. Joseph II's highhanded foreign policy served to disturb Louis XVI (1754–1793) and his ministers. A faction at court began to push the French monarch toward an anti-Austrian policy by 17907. On 14 October, Marie was taken to face her enemies at the Revolutionary Tribunal. The charges against her were more an attack on her person than her politics; the headlines that had filled the libelles were presented as fact. They accused her of organising orgies in Versailles, orchestrating the massacre of the Swiss guards, sending France’s money to Austria and, most appalling of all, sexually abusing her own son. At this she refused to respond, simply uttering: “If I make no reply, it is because I cannot. I appeal to all mothers in this audience.” Her unbelievable defiance and strength despite the horrors she had endured was remarkable, but the verdict had been decided before she even entered the room. Guilty.

In her execution, Marie displayed the courage and markings of a true queen until the end. But that was the problem exactly: she was a queen in every sense of the word. She was born to be a queen, trained to be a queen, had performed her duties as queen throughout her entire life – but France didn’t want a queen. Her lifeless body was dragged from the guillotine and tossed in a cart and her head was thrown between her legs. Her remains were dumped in an unmarked grave, but the memory of Marie Antoinette would live on as France’s hated, but eternal, queen.

In her execution, Marie displayed the courage and markings of a true queen until the end. But that was the problem exactly: she was a queen in every sense of the word. She was born to be a queen, trained to be a queen, had performed her duties as queen throughout her entire life – but France didn’t want a queen. Her lifeless body was dragged from the guillotine and tossed in a cart and her head was thrown between her legs. Her remains were dumped in an unmarked grave, but the memory of Marie Antoinette would live on as France’s hated, but eternal, queen.