THE PRE - COLUMBIAN ERA (1492) AND THE FIRST OWNERS OF AMERICA. INCORPORATES ALL PERIOD SUBDIVISION IN THE HISTORY AND PREHISTORY OF THE AMERICAS BEFORE THE APPEARANCE OF SIGNIFICANT EUROPEAN INFLUENCES ON AMERICAN CONTINENTS.

Aztec

temples were usually found at the top of pyramids and they are often

called temple-pyramids. Designed using ancient Mesoamerican

architectural traditions that went back thousands of years ,

temple-pyramids were tall structures forming four main platforms, with

grand stairways running up one side.

Aztec

temples were usually found at the top of pyramids and they are often

called temple-pyramids. Designed using ancient Mesoamerican

architectural traditions that went back thousands of years ,

temple-pyramids were tall structures forming four main platforms, with

grand stairways running up one side.

Cortes'

Encounter With Montezuma II Spanih's Hernando Cortes landed on the

coast of Mexico with around 500 men. He had 16 horses and had heard

rumors of the Aztecs possesing a huge and wealthy empire. In November of

1519, Cortes and his men entered the Aztec capital city of

Tenochtitlan. Walking for eight miles across Lake Texcoco to

Tenochtitlan, Cortes was greeted by the Aztec emperor Montezuma II.Montezuma

II, also spelled Moctezuma, (born 1466—died c. June 30, 1520,

Tenochtitlán, within modern Mexico City), ninth Aztec emperor of Mexico,

famous for his dramatic confrontation with the Spanish conquistador

Hernán Cortés.In 1502 Montezuma succeeded his uncle Ahuitzotl as the

leader of an empire that had reached its greatest extent, stretching to

what is now Honduras and Nicaragua, but that was weakened by the

resentment of the subject tribes to the increasing demands for tribute

and victims for the religious sacrifices.

Cortes'

Encounter With Montezuma II Spanih's Hernando Cortes landed on the

coast of Mexico with around 500 men. He had 16 horses and had heard

rumors of the Aztecs possesing a huge and wealthy empire. In November of

1519, Cortes and his men entered the Aztec capital city of

Tenochtitlan. Walking for eight miles across Lake Texcoco to

Tenochtitlan, Cortes was greeted by the Aztec emperor Montezuma II.Montezuma

II, also spelled Moctezuma, (born 1466—died c. June 30, 1520,

Tenochtitlán, within modern Mexico City), ninth Aztec emperor of Mexico,

famous for his dramatic confrontation with the Spanish conquistador

Hernán Cortés.In 1502 Montezuma succeeded his uncle Ahuitzotl as the

leader of an empire that had reached its greatest extent, stretching to

what is now Honduras and Nicaragua, but that was weakened by the

resentment of the subject tribes to the increasing demands for tribute

and victims for the religious sacrifices.

What does Pre-Columbian mean? All of the Americas were pre-Columbian before 1492, but European influence didn’t happen everywhere all at the same time. Cultures in what England is now northern Canada would have France been influenced much later than Netherlands Culture in what is now the eastern Russia-United States. Spain claimed The European influence would also have been different based on what European nations claimed what territory.Pre-Columbian is used especially often in the context of the great indigenous civilizations of the Americas, such as those of Mesoamerica (the Olmec, the Toltec, the Teotihuacano, the Zapotec, the Mixtec, the Aztec, and the Maya) and the Andes (Inca, Moche, Chibcha, Cañaris).Many pre-Columbian civilizations established characteristics and hallmarks which included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies.Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first permanent European arrivals (c. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are known only through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with this period, and are also known from historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Maya, had their own written records.However, most Europeans of the time largely viewed such texts as heretical, and much was destroyed in Christian pyres. Only a few hidden documents remain today, leaving modern historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.According to both indigenous American and European accounts and documents, American civilizations at the time of European encounter possessed many impressive accomplishments.For instance, the Aztecs built one of the most impressive cities in the world, Tenochtitlan, the ancient site of Mexico City, with an estimated population of 200,000. American civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in astronomy and mathematics.Where they persist, the societies and cultures which are descended from these civilizations may now be substantively different in form from that of the original. However, many of these peoples and their descendants still uphold various traditions and practices which relate back to these earlier times, even if combined with those that were more recently adopted.From about 700 to 1400 AD, Cahokia was apparently one of the biggest cities in the world. At its height it had 15,000 residents. The complex society at Cahokia, part of the Native American Mississippian Culture, prospered in the fertile lands off of the Mississippi River across the river from modern St. Louis, Missouri.These people too were local, Slater and his group’s research reveals. The people in the brutalized group appear different morphologically from other people buried at Cahokia but resemble each other, suggesting they were from an isolated community.A mass grave called Feature 214 in Mound 72 had 24 bodies carefully arranged in two layers buried around 1000 AD. Feature 105, from about 50 years later, had more than 50 bodies neatly laid out. But Feature 229 had one layer of 15 men and women laid to rest on cedar litters, and the lower mass grave of the 39 men and women who were mutilated and then unceremoniously dumped into the grave.Agriculture arose sometime between nine- and five-thousand years ago, almost simultaneously in the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. Mesoamericans in modern-day Mexico and Central America relied upon domesticated maize (corn) to develop the hemisphere’s first settled population around 1,200 BCE.8 Corn was high in caloric content, easily dried and stored, and, in Mesoamerica’s warm and fertile Gulf Coast, could sometimes be harvested twice in a year. Corn as well as other Mesoamerican crops spread across North America and continues to hold an important spiritual and cultural place in many Native communities.Around the year 1050, Cahokia experienced what one archeologist has called a “big bang,” which included “a virtually instantaneous and pervasive shift in all things political, social, and ideological.”15 The population grew almost 500 percent in only one generation, and new people groups were absorbed into the city and its supporting communities.16 By 1300, the once powerful city had undergone a series of strains that led to collapse. Scholars previously pointed to ecological disaster or slow depopulation through emigration, but new research instead emphasizes mounting warfare, or internal political tensions. Environmental explanations suggest that population growth placed too great a burden on the arable land. Others suggest the demand for fuel and building materials led to deforestation, erosion, and or an extended drought. Recent evidence, including defensive stockades, suggests that political turmoil among the ruling elite and threats from external enemies may explain the end of the once great civilization.Before the arrival of Europeans, then, the indigenous past was both well honored and open to reinterpretation by the descendants of those who came before. This was a process that depended upon and lent new meanings to visual culture, as peoples actively recast old forms and places, reworking and reinterpreting them. It was also a process that continued after the arrival of Europeans, but was made more difficult by the profound and devastating changes that were unleashed soon after 1492. The conquistadors had little interest in indigenous histories: many an Inka witnessed the Spanish conquistadors destroying ancient shrines—places where the dead could speak to the living—in their zealous search for silver and gold. Often Spaniards viewed local history—embedded in objects and architectural spaces—as an impediment to conquest. Thus, Aztecs saw their glorious capital city reduced to rubble, the life-size portraits of the Aztec kings gouged off the living rock, and, as seen below, sacred objects and manuscripts put to the torch. The transmission of oral histories and living memories was severely reduced by the countless deaths brought by new diseases. While about twenty-five million Americans witnessed the dawn of the 16th century, fewer than one million would see the 17th.Across the Americas, the history of indigenous cultures is so long and so vibrant that by 1500, hundreds of histories could be found inscribed in abandoned cities and half-buried settlements. In the Yucatán, the landscape was punctuated by crumbling ruins that had once been the center of dazzling whitewashed cities. Built by the ancestors of the Maya, many sites still held hieroglyphic texts carved in stone or painted inside building walls. In the highlands of Peru, Machu Picchu, seen in the photograph, had been an Inka royal retreat. The city was abandoned probably in the early 16th century; its walls overgrown with orchid and bromeliad, even as vibrant Andean communities made their living nearby. Chaco Canyon in northern New Mexico was home to ancestral Puebloan people between 900 and 1300 CE. As many as 15,000 people lived in the Chaco Canyon complex in present-day New Mexico.Sophisticated agricultural practices, extensive trading networks, and even the domestication of animals like turkeys allowed the population to swell. Massive residential structures, built from sandstone blocks and lumber carried across great distances, housed hundreds of Puebloan people. Puebloan spirituality was tied both to the earth and to the heavens, as generations carefully charted the stars and designed homes in-line with the path of the sun and moon.The Puebloan people of Chaco Canyon faced several ecological challenges, including deforestation and over-irrigation, which ultimately caused this community to collapse and its people to disperse to smaller settlements. An extreme fifty-year drought began in 1130. Shortly thereafter, Chaco Canyon was deserted. New groups filled this land, including the Apache and Navajo, both of whom adopted several Puebloan customs. The same drought that plagued the Pueblo also likely affected the Mississippian peoples of the American Midwest and South. The Mississippians developed one of the largest civilizations north of modern-day Mexico. Roughly one-thousand years ago, the largest Mississippian settlement, Cahokia, located just east of modern-day St. Louis, peaked at a population of between 10,000-30,000. It rivaled contemporary European cities in size. No American city, in fact, would match Cahokia’s peak population levels until after the American Revolution. The city itself spanned 2,000 acres and centered around Monks Mound, a large earthen hill that rose ten-stories and was larger at its base than the great pyramids of Egypt. As with many of the peoples who lived in the Woodlands, life and death in Cahokia were linked to the movement of the stars, sun, and moon, and their ceremonial earthwork structures reflect these important structuring forces.Cahokia was politically organized around chiefdoms, a hierarchical, clan-based system that gave leaders both secular and sacred authority. The size of the city and the extent of its influence suggests that the city relied on a number of lesser chiefdoms under the authority of a paramount leader. Social stratification was partly preserved through frequent warfare. War captives would be enslaved, and these captives formed an important part of the economy in the North American southeast. Native American slavery was not based on holding people as property. Instead, Native Americans understood slaves as people who lacked kinship networks. Slavery, then, was not always a permanent condition. Very often, a former slave could become a fully integrated member of the community. Adoption or marriage could enable a slave to enter a kinship network and join the community. Slavery and captive trading became an important way that many Native communities regrew and gained or maintained power.Around the year 1050, Cahokia experienced what one archeologist has called a “big bang,” which included “a virtually instantaneous and pervasive shift in all things political, social, and ideological.”The population grew almost 500 percent in only one generation, and new people groups were absorbed into the city and its supporting communities.By 1300, the once powerful city had undergone a series of strains that led to collapse. Scholars previously pointed to ecological disaster or slow depopulation through emigration, but new research instead emphasizes mounting warfare, or internal political tensions. Environmental explanations suggest that population growth placed too great a burden on the arable land. Others suggest the demand for fuel and building materials led to deforestation, erosion, and or an extended drought. Recent evidence, including defensive stockades, suggests that political turmoil among the ruling elite and threats from external enemies may explain the end of the once great civilization.

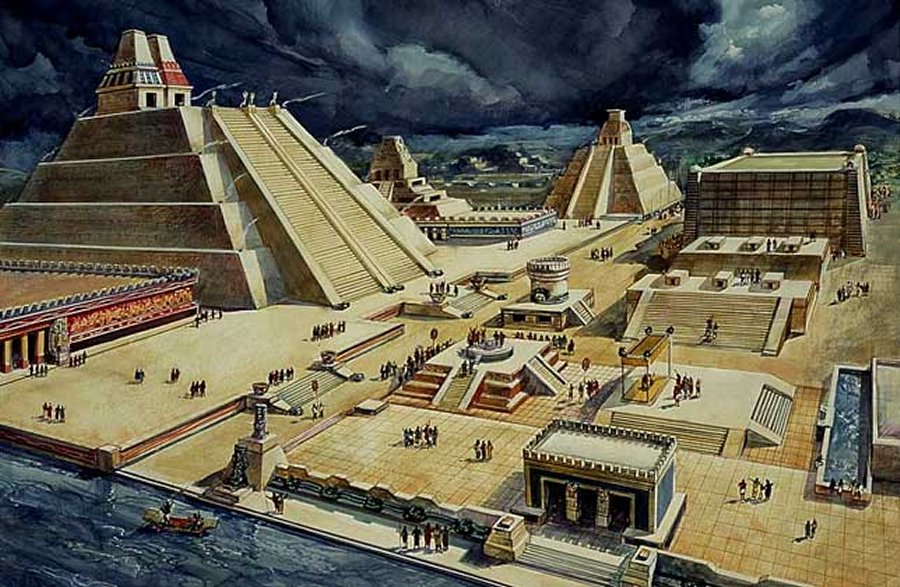

The

central plaza of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital, included a pyramid

temple to the war god, left, temples to other gods, and palaces.was a

large Mexica city-state in what is now the center of Mexico City.

Founded on June 20, 1325, the city was built on an island in what was

then Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. The city was the capital of

the expanding Aztec Empire in the 15th century[1] until it was captured

by the Spanish in 1521.At its peak, it was the largest city in the

Pre-Columbian Americas. It subsequently became a cabecera of the

Viceroyalty of New Spain. Today, the ruins of Tenochtitlan are in the

historic center of the Mexican capital.

The

central plaza of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital, included a pyramid

temple to the war god, left, temples to other gods, and palaces.was a

large Mexica city-state in what is now the center of Mexico City.

Founded on June 20, 1325, the city was built on an island in what was

then Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. The city was the capital of

the expanding Aztec Empire in the 15th century[1] until it was captured

by the Spanish in 1521.At its peak, it was the largest city in the

Pre-Columbian Americas. It subsequently became a cabecera of the

Viceroyalty of New Spain. Today, the ruins of Tenochtitlan are in the

historic center of the Mexican capital.

North American communities were connected by kin, politics, and culture and sustained by long distance trading routes. The Mississippi River served as a particularly important trade artery, but all of the continent’s waterways were vital to transportation and communication.Cahokia became a key trading center partly due to its position near the Mississippi, Illinois, and Missouri Rivers. These rivers created networks that stretched from the Great Lakes to the American Southeast. Archaeologists can identify materials, like seashells, that traveled over a thousand miles to reach the center of this civilization. At least 3,500 years ago, the community at what is now Poverty Point, Louisiana, had access to copper from present-day Canada and flint from modern-day Indiana. Sheets of Mica found at the sacred Woodland Serpent Mound site near the Ohio River came from the Allegheny Mountains, and obsidian from nearby earthworks came from Mexico. Turquoise from the Greater Southwest was used at Teotihuacan 1200 years ago.In the Eastern Woodlands, many Native American societies lived in smaller dispersed communities in order to take advantage of the rich soils and abundant rivers and streams. Their hundreds of settlements, stretching from southern Massachusetts through Delaware, were loosely bound together by political, social, and spiritual connections.Dispersed and relatively independent, Lenape communities were bound together by oral histories, ceremonial traditions, consensus-based political organization, kinship networks, and a shared clan system. Kinship tied the various Lenape communities and clans together and society was organized along matrilineal lines. Marriage occurred between clans, and a married man would join the clan of his wife. Lenape women wielded authority over marriages, households, agricultural production, and even may have played a significant part in determining the selection of leaders, called sachems. Dispersed authority, small settlements, and kin-based organization contributed to the long-lasting stability and resilience of Lenape communities.18 One or more sachems governed Lenape communities by the consent of their people. Lenape sachems acquired their authority by demonstrating wisdom and experience. This differed from the hierarchical organization of many Mississippian cultures. Large gatherings did exist however, as dispersed communities and their leaders gathered together for ceremonial purposes or to make big decisions. Sachems spoke for their people in larger councils that included men, women, and elders. The Lenape experienced occasional tensions with other indigenous groups like the Iroquois to the north or Susquehannock to the south, but the lack of defensive fortifications near Lenape communities leads archeologists to believe that the Lenapes avoided large-scale warfare. The continued longevity of Lenape societies, which began centuries before European contact, was also due to their skills as farmers and fishers. Along with the “Three Sisters,” Lenape women planted tobacco, sunflowers, and gourds. They harvested fruits and nuts from trees and also cultivated numerous medicinal plants which they used with great proficiency. The Lenapes organized their communities to take advantage of growing seasons and also the migration patterns of animals and fowl that were a part of their diet. During planting and harvesting seasons, Lenapes gathered together in larger groups to coordinate their labor and take advantage of local abundance. As proficient fishers, they organized seasonal fish camps to net shellfish and catch shad. Lenapes wove nets, baskets, mats, and a variety of household materials from the readily available rushes found along the streams, rivers, and coasts. They made their homes in some of the most fertile and abundant lands in the Eastern Woodlands and used their skills to create a stable and prosperous civilization. The first Dutch and Swedish settlers who encountered the Lenapes in the seventeenth century recognized Lenape prosperity and quickly sought their friendship. Their lives came to depend on it.In the Pacific Northwest, the Kwakwaka’wakw, Tlingits, Haidas, and hundreds of other peoples, speaking dozens of languages, thrived due to the moderate climate, lush forests and many rivers. The peoples of this region depended upon salmon for survival and valued it accordingly. Images of salmon decorated totem poles, baskets, canoes, oars, and other tools. The fish was treated with spiritual respect and its image represented prosperity, life, and renewal. Sustainable harvesting practices ensured the survival of salmon populations. The Coast Salish people and several others celebrated the First Salmon Ceremony when the first migrating salmon was spotted each season. Elders closely observed the size of the salmon run and would delay harvesting to ensure that a sufficient number survived to spawn and return in the future.Men commonly used nets, hooks, and other small tools to capture salmon as they migrated upriver to spawn. Massive cedar canoes, as long as 50 feet and carrying as many as 20 men, also enabled extensive fishing expeditions in the Pacific Ocean, where skilled fishermen caught halibut, sturgeon, and other fish, sometimes hauling thousands of pounds in a single canoe.

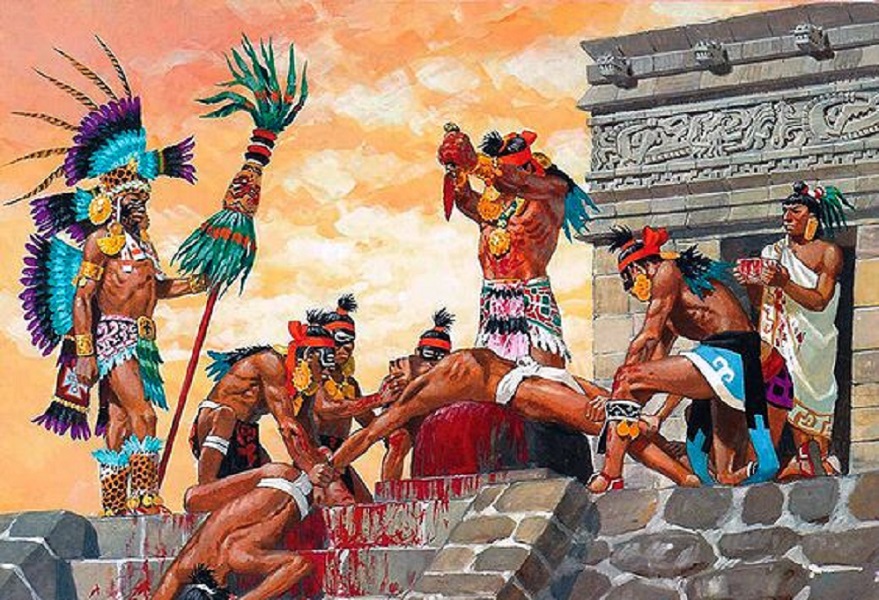

One

hundred years before its fall, the Aztec Empire went through an

incredible change. The emperor’s son, Tlacaelel, declared that the god

of war, Huitzilopochtli, was to be the highest of all gods.From then on,

the Aztecs lived in service of the god of war. Human sacrifice became a

massive part of Aztec society, with hundreds of thousands of people

slaughtered each year as offerings to the gods.

One

hundred years before its fall, the Aztec Empire went through an

incredible change. The emperor’s son, Tlacaelel, declared that the god

of war, Huitzilopochtli, was to be the highest of all gods.From then on,

the Aztecs lived in service of the god of war. Human sacrifice became a

massive part of Aztec society, with hundreds of thousands of people

slaughtered each year as offerings to the gods.

The

combination of population density and food surplus created a unique

social organization centered around elaborate feasts, called potlatches.

These potlatches celebrated births and weddings as well as determined

social status. A party would last for days and the host would

demonstrate his wealth and power by feeding and entertaining guests with

food, artwork, and performances. The more the host gave away, the more

prestige and power they had within the group. Some men saved for decades

to host an extravagant potlach that would in turn give him greater

respect and power within the community.Centuries

later, Cahokia's meteoric rise and fall remain a mystery. It was

booming in 1050, and by 1400 its population had disappeared, leaving

behind a landscape completely geoengineered by human hands. Looking for

clues about its history, archaeologists

dig through the thick, wet, stubborn clay that Cahokians once used to

construct their mounds. Buried beneath just a few feet of earth are

millennia-old building foundations, trash pits, the cryptic remains of

public rituals, and in some places, even, graves.North

America’s indigenous peoples shared some broad traits. Spiritual

practices, understandings of property, and kinship networks differed

markedly from European arrangements. Most Native Americans did not

neatly distinguish between the natural and the

supernatural. Spiritual power permeated their world and was both

tangible and accessible. It could be appealed to and harnessed. Kinship

bound most Native North American people together. Most peoples lived in

small communities tied by kinship networks. Many Native cultures

understood ancestry as matrilineal: family and clan identity proceeded

along the female line, through mothers and daughters, rather than

fathers and sons. Fathers, for instance, would often join mothers’

extended families and sometimes even a mother’s brothers would take a

more direct role in child-raising than biological fathers. Mothers could

therefore often wield enormous influence at local levels and men’s

identities and influence often depended on their relationships to women.

Native American culture meanwhile generally afforded greater sexual and

marital freedom than European cultures did. Women often chose their

husbands, and divorce often was a relatively simple and straightforward

process. Moreover, most Native peoples’ notions of property rights

differed markedly from Europeans’ notions of property. Native Americans

generally felt a personal ownership of tools, weapons, or other items

that were actively used, and this same rule applied to land and crops.

Groups and individuals exploited particular pieces of land, and used

violence or negotiation to exclude others. But the right to the use of

land did not imply the right to its permanent possession.Native

Americans had many ways of communicating, including graphic ones, and

some of these artistic and communicative technologies are still used

today. For example, Algonkian-speaking Ojibwes, used birch-bark scrolls

to record medical treatments, recipes, songs, stories, and more. Other

Eastern Woodland peoples wove plant fibers, embroidered skins with

porcupine quills, and modeled the earth to make sites of complex

ceremonial meaning. On the Plains, artisans wove buffalo hair and

painted on buffalo skins; in the Pacific Northwest weavers wove goat

hair into soft textiles with particular patterns. Maya, Zapotec, and

Nahua ancestors in Mesoamerica painted their histories on plant-derived

textiles and carved them into stone. In the Andes, Inka recorders noted

information in the form of knotted strings, or Khipu.Two

thousand years ago, some of the largest culture groups in North America

were the Puebloan groups, centered in the current-day Greater Southwest

(the southwestern US and northwestern Mexico), the Mississippian groups

located along the Great River and its Woodland tributaries, and the

Mesoamerican groups of the areas now known as central Mexico and the

Yucatan. Previous developments in agricultural technology enabled the

explosive growth of the large early societies, such as that at

Tenochtitlan in the Central Mexican Valley, Cahokia along the

Mississippi River, and in the desert oasis areas of the Greater

Southwest.Native Americans

had many ways of communicating, including graphic ones, and some of

these artistic and communicative technologies are still used today. For

example, Algonkian-speaking Ojibwes, used birch-bark scrolls to record

medical treatments, recipes, songs, stories, and more. Other Eastern

Woodland peoples wove plant fibers, embroidered skins with porcupine

quills, and modeled the earth to make sites of complex ceremonial

meaning. On the Plains, artisans wove buffalo hair and painted on

buffalo skins; in the Pacific Northwest weavers wove goat hair into soft

textiles with particular patterns. Maya, Zapotec, and Nahua ancestors

in Mesoamerica painted their histories on plant-derived textiles and

carved them into stone. In the Andes, Inka recorders noted information

in the form of knotted strings, or Khipu.Two

thousand years ago, some of the largest culture groups in North America

were the Puebloan groups, centered in the current-day Greater Southwest

(the southwestern US and northwestern Mexico), the Mississippian groups

located along the Great River and its Woodland tributaries, and the

Mesoamerican groups of the areas now known as central Mexico and the

Yucatan. Previous developments in agricultural technology enabled the

explosive growth of the large early societies, such as that at

Tenochtitlan in the Central Mexican Valley, Cahokia along the

Mississippi River, and in the desert oasis areas of the Greater

Southwest.

These

people too were local, Slater and his group’s research reveals. The

people in the brutalized group appear different morphologically from

other people buried at Cahokia but resemble each other, suggesting they

were from an isolated community .

These

people too were local, Slater and his group’s research reveals. The

people in the brutalized group appear different morphologically from

other people buried at Cahokia but resemble each other, suggesting they

were from an isolated community .